The Numbers Don't Lie

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a long-term series exploring the history of Kansas City and the financial ramifications of its development pattern. It is based on a detailed survey of fiscal geography—its sources of tax revenue and its major expenses, its street network and its historical development patterns—conducted by geoanalytics firm Urban3. Here are all the articles in the series:

Kansas City's Fateful Suburban Experiment • Is Kansas City Still Living on Its Streetcar-Era Inheritance? • "Kansas City's Blitz": How Freeway-Building Blew Up Urban Wealth • The Road to Insolvency is Long • Asphalt City: How Parking Ate an American Metropolis •

The Local Case for Reparations • Ready, Fire Aim: Tax Incentives in Kansas City (Part 1) •

The Opportunity Cost of Tax Incentives in Kansas City (Part 2) • The Numbers Don’t Lie •

Kansas City Has Everything It Needs

In Chapter 7 of Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity, I describe the data analytics firm, Urban3’s, approach to analyzing the financial productivity of cities. The value per acre analysis that they conduct — literally the amount of wealth produced per acre of land consumed — was a common metric for American cities prior to the Great Depression. And of course it would be; when you don’t have resources to waste — and most American cities of that era didn’t — squeezing a high return out of all your investments was critical. From my book:

Joe and I searching the Harvard Graduate School of Design library for forgotten wisdom.

The traditional development pattern – even when blighted and occupied by the poorest people in our communities – is financially more productive than our post-war neighborhoods, regardless of their condition. Across North America, our poor neighborhoods tend to subsidize our wealthy neighborhoods. The only places this doesn’t hold true are communities where the poor have been displaced out to the edge.

None of this would surprise our ancestors. One evening, Joe and I were wandering through the library at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, where Joe had done his graduate work. We were browsing town planning books from the late 1800s and early twentieth century. Repeatedly in these publications, we came across a simple metric they used for measuring success: value per acre.

I have a civil engineering degree, a graduate degree in urban and regional planning, and decades of experience. Joe has an architecture degree, graduate work in planning, and a similar level of experience. We were never taught about value per acre. It is lost wisdom, abandoned along with so many of our ancestors’ hard-gained insights.

Kansas City, like most American cities, has spent nearly three generations destroying its own wealth, depleting its resources and adding unfathomable liabilities in its confusion over the difference between growth and wealth creation. An examination of specific parcels gives a glimpse of what has been lost but also the possibilities that are still available if Kansas City adopts a Strong Towns approach.

Click to view larger

The city has invested immense sums of money making Linwood Boulevard and Main Street into wealth-crushing stroads, and it shows. The Costco and the Home Depot located near the Linwood and Main intersection represent the pinnacle of the post-war development pattern, yet the financial productivity of the site is less than $200,000 per acre. When one notes that big box stores are cheaply-built structures that aren’t expected to last a generation, that’s a substantial amount of long-term public investment supporting a pretty fragile and unproductive private investment.

Click to view larger

Nearby are some modest apartment buildings that have already been with Kansas City longer than the Costco and Home Depot can be expected to last. Along East 27th Street is an apartment with financial productivity of $220,000 per acre. Along Warwick Avenue is another at $630,000 per acre, three times the productivity of the big box stores. Even more intense is the Jefferson Street Apartments at nearly $1.2 million per acre.

Each of these apartment buildings is not only more productive and enduring that the big box stores, they all fit into the neighborhood. They are all built within the context of their surroundings, adding value to the properties around them. The big box style of development creates a limited amount of value on a single site, but it also comes at the expense of the properties around it. Nobody wants their home or business to front a long barren wall. It’s the antithesis of neighborly.

Home Depot and Costco displace land that was or could be living units, but they also displace neighborhood scale commercial, both physically by occupying the space and financially by crowding them out of the market. That is unfortunate because neighborhood commercial not only creates opportunities for entrepreneurs — the kind that transform a community — but they create lots of jobs.

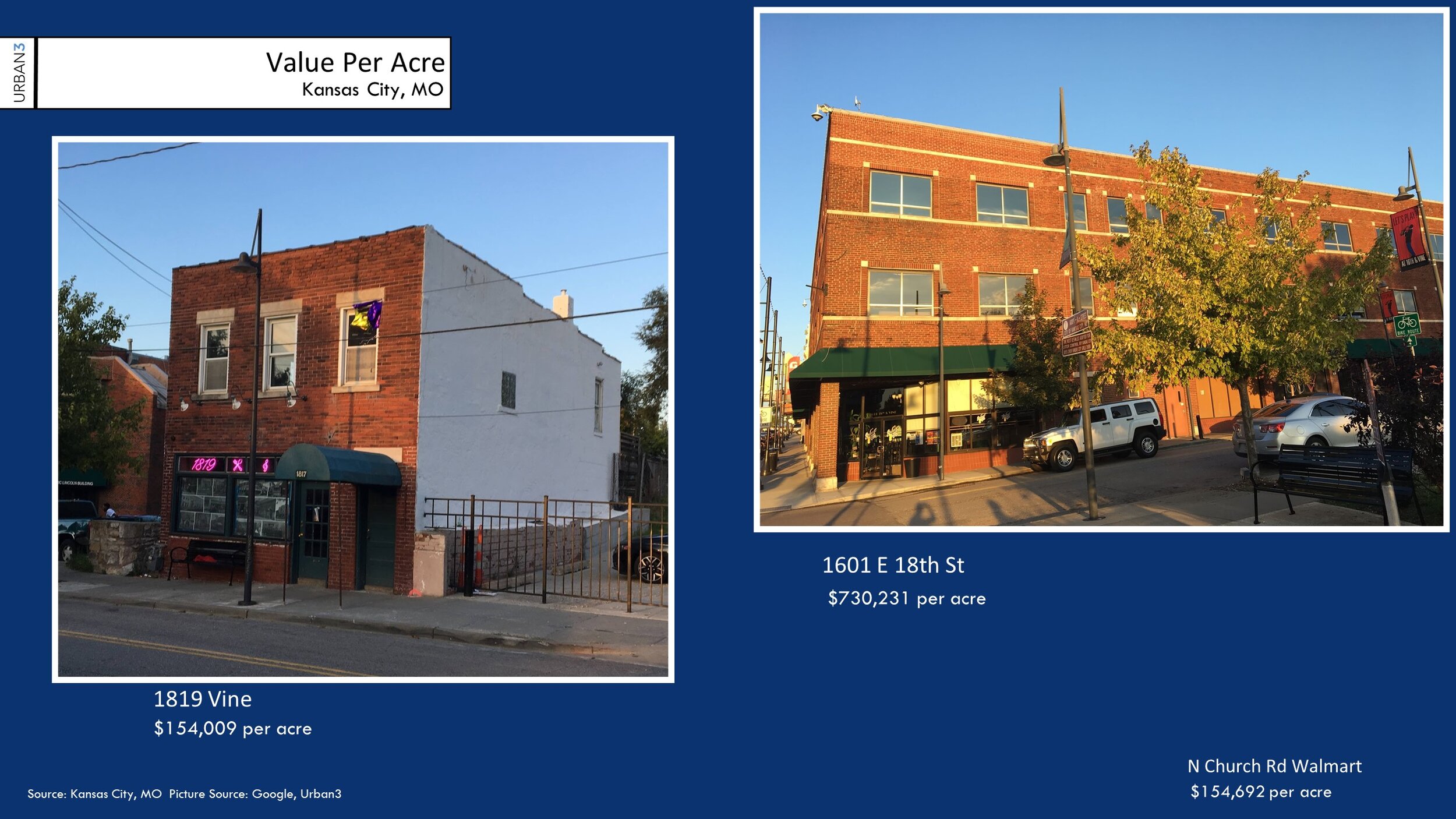

A barbershop at 1819 Vine ($150,000 per acre) with a living unit above is the quintessential entrepreneurial layout. A retail block with two floors of housing — a third-generation form of commercial real estate — yields more than $700,000 per acre in productivity.

In the Westport neighborhood, a commercial strip along Main Street has productivity many multiples of the big box stores. This is neighborhood fabric that has been in place for decades, sustaining the community’s tax base and creating jobs and opportunity. The main thing keeping these structures from exploding in value is the toxic design of Main Street, which is built as a traffic corridor instead of a neighborhood center.

Further along Main Street is another standard mixed-use building, the kind of structure that was commonly built in Kansas City neighborhoods before the post-war Suburban Experiment made them obsolete. At $2 million per acre, it is ten times more productive than the big boxes.

The Costco and Home Depot buildings are designed for a single purpose, with no evolution of the site anticipated. A primary tax-reduction strategy of big box commercial is to keep property values as low as possible. There is a reason why we don’t look forward to a day when the land underneath Costco becomes so valuable that the owners are prompted to add a second story or tear it down and redevelop the site. It doesn’t happen. Big box is where valuations go to die.

In contrast, Kansas City has numerous examples where buildings site have progressed through generations of redevelopment, with rising land values prompting increasingly intense development without the need for public subsidy.

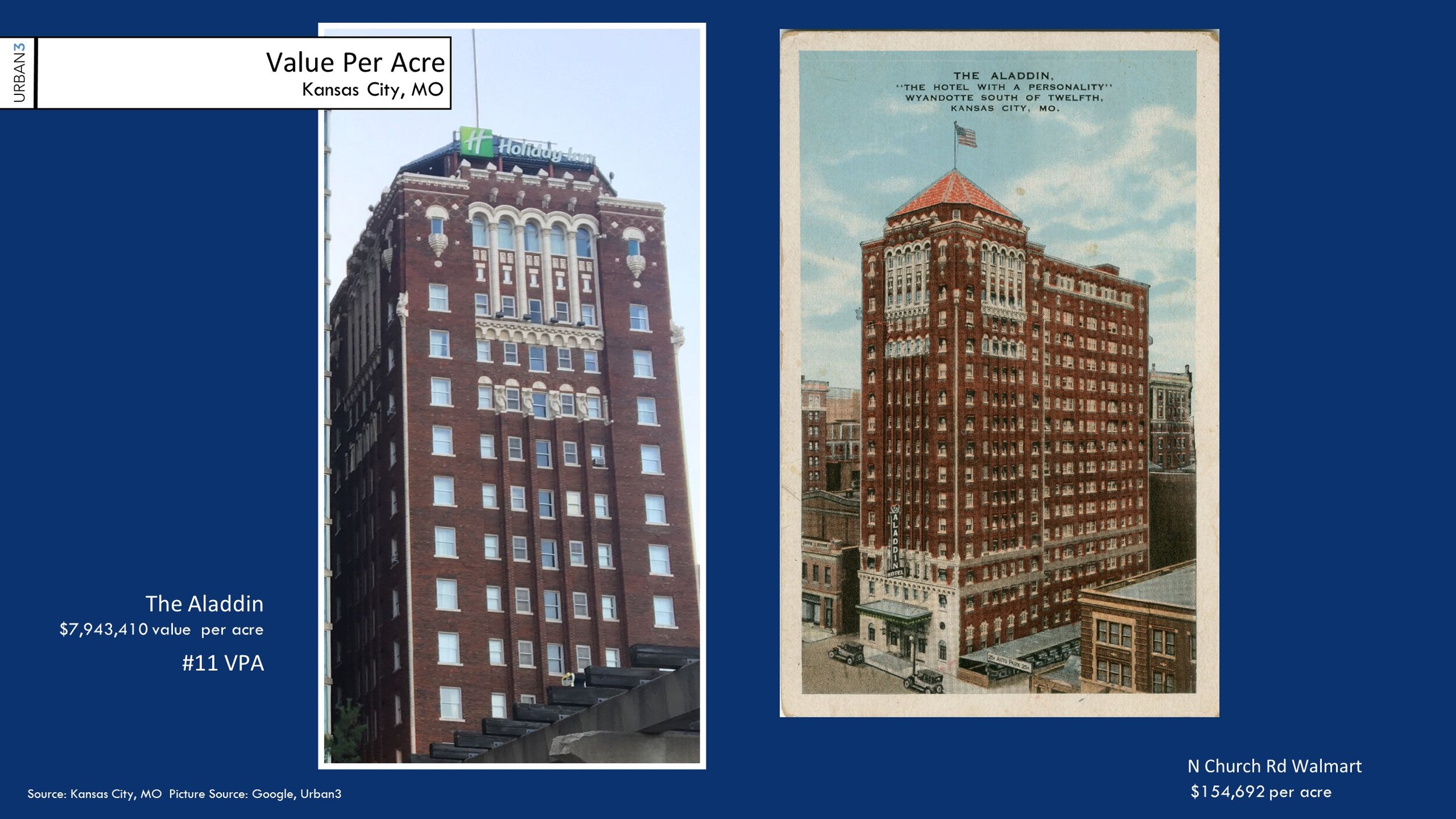

One example is the Aladdin Hotel, a building that has hosted meetings, weddings, and overnight guests for over a century. At $8 million in value per acre, the site is 40 times more productive than the two big box stores.

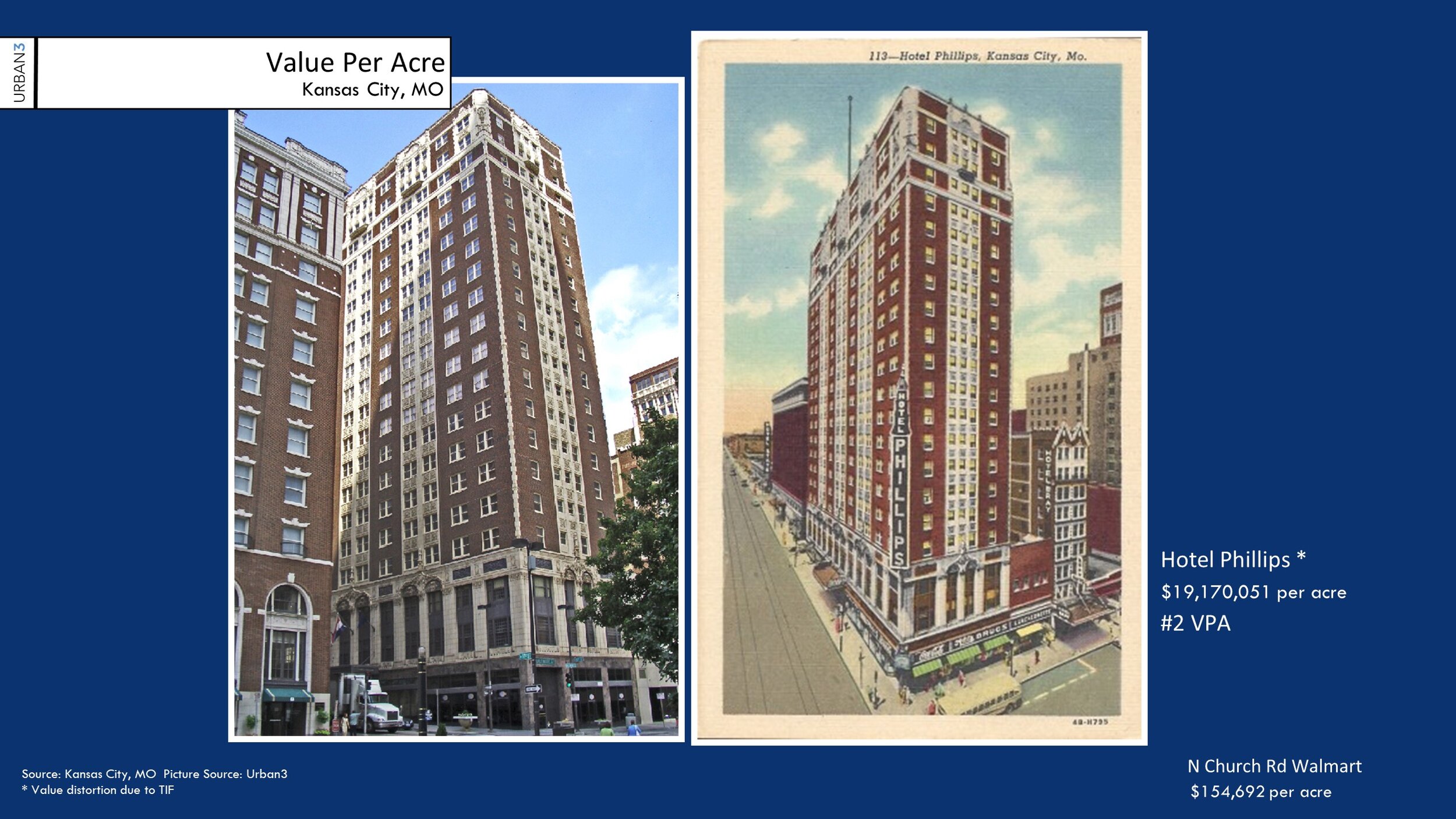

That’s impressive, but not nearly as spectacular as the Hotel Phillips. At $19 million per acre, it has the second highest financial productivity of any property in Kansas City.

While Costco and Home Depot are the pinnacle of development in the auto-oriented pattern of development, these two hotels were the pinnacle of development in their day. A century ago, Kansas City residents would have looked at these buildings — and everything around them — and felt supremely confident about the future of their community. Their incremental approach to wealth-building had birthed these major investments, buildings whose owners, ever since, have been requiring little in terms of public service, yet paying substantially in terms of taxes into the community. That’s what real success looks like.

The numbers here don’t lie. Kansas City has coveted and embraced big box development, and other auto-oriented development patterns, within its core neighborhoods. The overall effect has been to lower the tax base — to decrease the wealth of the community — while doing nothing to lower the cost of providing services.

In many places, the city has invested heavily in stroads and other auto infrastructure, reducing the desirability of its core neighborhoods while putting the businesses there at a competitive disadvantage. In financial terms, the community has actually paid a premium to experience a reduced return on investment.

Fortunately, there is nothing keeping Kansas City, and other North American cities that have adopted this same approach, from learning the simple math lesson their city founders clearly understood.

That simple lesson: To have enduring prosperity, a community cannot squander its land; it must develop in ways that are financially productive.

In Kansas City, one need only do the math to identify a long list of examples for how this can be accomplished.

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.