This South American City Illustrates How Incremental Development Works

There is a consistent pattern to how cities, throughout most of human history and across most of the world, grow and develop over time.

It starts with the bare minimum viable development in a location where there’s some compelling reason to be. Often this means a handful of shacks, nothing more. Then, its inhabitants gradually improve what they’ve built over time, at the same time as new inhabitants arrive and settle on the outskirts, expanding the city’s boundaries. Sometimes a place that begins this way develops over time into a large metropolis. Sometimes it doesn’t, remaining a small town, or even losing its economic reason to be and fading away.

This pattern predominated in the United States before the mid-twentieth century:

Simple, utilitarian structures comprise the first foothold in a place people have discovered a reason to be. But they give way as the occupants build up a bit of wealth to higher quality and more permanent buildings. Public infrastructure improves in tandem with private development. In this photo of Brainerd, Minnesota from the 1930s, you can see that not only have the simple wooden buildings pictured above been replaced by multi-story edifices of brick and stone, the street has acquired curbs and a sewer (note the manhole cover):

This pattern doesn't just exhibit itself in a single place over time, though. It also expresses itself as a gradient across space. As the land in the center of town becomes more valuable—because the city has a growing population and more concentrated economic activity—there's an incentive to redevelop those lots with bigger, taller, more elaborate buildings and to occupy the land at higher densities. But that expensive land excludes people who can't afford to buy and build on it. So where do they go?

Historically, and throughout the world, the answer is: to the outskirts. Land is cheaper there, because there is less proximity to all the amenities downtown has to offer. You thus see a consistent pattern: the center of activity is in the core. The core has the most wealth, the most commerce, the greatest density, the grandest structures and the most advanced public infrastructure. The cheap land is on the periphery, and that's where the poor settle and make a start for themselves.

The below graphic illustrates the pattern of land productivity that emerges across the city as a whole, where land values peak in the core and decrease toward the periphery, while rising everywhere over time. (The three years labeled, which made sense in the graphic’s original context, are arbitrary for our purposes here—you could substitute any comparable passage of time and the point remains the same.)

The Suburban Experiment in the post-WWII era in the west disrupted this historic pattern. By spending large amounts of taxpayer money to leverage even vaster amounts of private capital, we remade a continent along a very different model: now the rich would live on the edge, in commuter suburbs, and the poor would be relegated to fading inner cities. Later decades have complicated this pattern, but it remains the case that the basic pattern that prevailed throughout history—expensive land and mature development in the center, cheap land and incremental development on the outskirts—is something you don't really find in U.S. or Canadian cities anymore.

That doesn't mean Americans can't see examples of what it looks like without cracking open a history book, though. You just have to travel outside of wealthy countries, to places where there isn't a history of vast government intervention disrupting the pattern of development that is a natural result of the economics of development by countless small, incremental investments.

La Paz at right in the valley; El Alto at left on the altiplano. Lake Titicaca and Peruvian border in background. Image via Google Maps.

La Paz and El Alto

La Paz, Bolivia boasts one of the most striking natural settings of any major city in the world. The historic core—founded in the 16th century by the Spanish on the site of a conquered Inca settlement—lies in a valley ringed by steep slopes, at a dizzying 12,000 feet above sea level in the Andes. Above the valley to the northwest lies the altiplano—a flat, nearly featureless alpine grassland where generations of Quechua and Aymara people have practiced small-scale agriculture and herding.

It's on this flat plain that you find El Alto—a city of 1 million people whose name roughly translates as "The Heights.” El Alto is a suburb of La Paz, but only in the most literal sense of the word "suburb." What it actually is is a booming city in its own right that has arisen from its role as the settler outskirts in the incremental development pattern: the barren altiplano was the place where rural people migrating to the city could obtain a piece of land and build a simple house.

Today, El Alto has grown into a city that comprises a striking object lesson in the incremental (but not slow!) growth of cities.

Google Street View imagery allows us to observe a cross section of this fast-growing city. Here's what you see when you enter El Alto on National Route 2, the main road into the city from the nearby Peruvian border at Lake Titicaca.

A Drive Into El Alto

As you approach the metropolis, the outskirts of El Alto, as this first slide show reveals, present a scene not unlike the photos of rows of pioneer shacks in the U.S. that would one day become great cities:

Aerial imagery makes clear the gradient in intensity of development, from more sparsely settled outskirts (background) to denser and more urbanized core (foreground):

As you enter the built-up area of the city, buildings end up spaced closer together with fewer gaps, have a more “finished” look, and are more likely to have multiple stories. You see more pedestrian activity, but little to no pedestrian infrastructure. There is more commerce. The physical design of everything is rudimentary: it is clear from the visuals that this is a relatively poor area.

A look down the side streets of these areas reveals quiet, unadorned neighborhoods of residential buildings and small, neighborhood-serving storefronts. Parks are (unfortunately) scarce in El Alto: Bolivia is a lower-income country and there is a corresponding lack of government investment in the public realm in all but its wealthiest places. But you do see the occasional soccer field, often associated with a church or school.

Continue further into El Alto on the main road, and now we start to see more intensive development. With the greater private investment we see commensurate improvements to the public realm: there are now sidewalks, planted medians, and pedestrian crossings. There is a greater diversity of architecture, and larger commercial buildings.

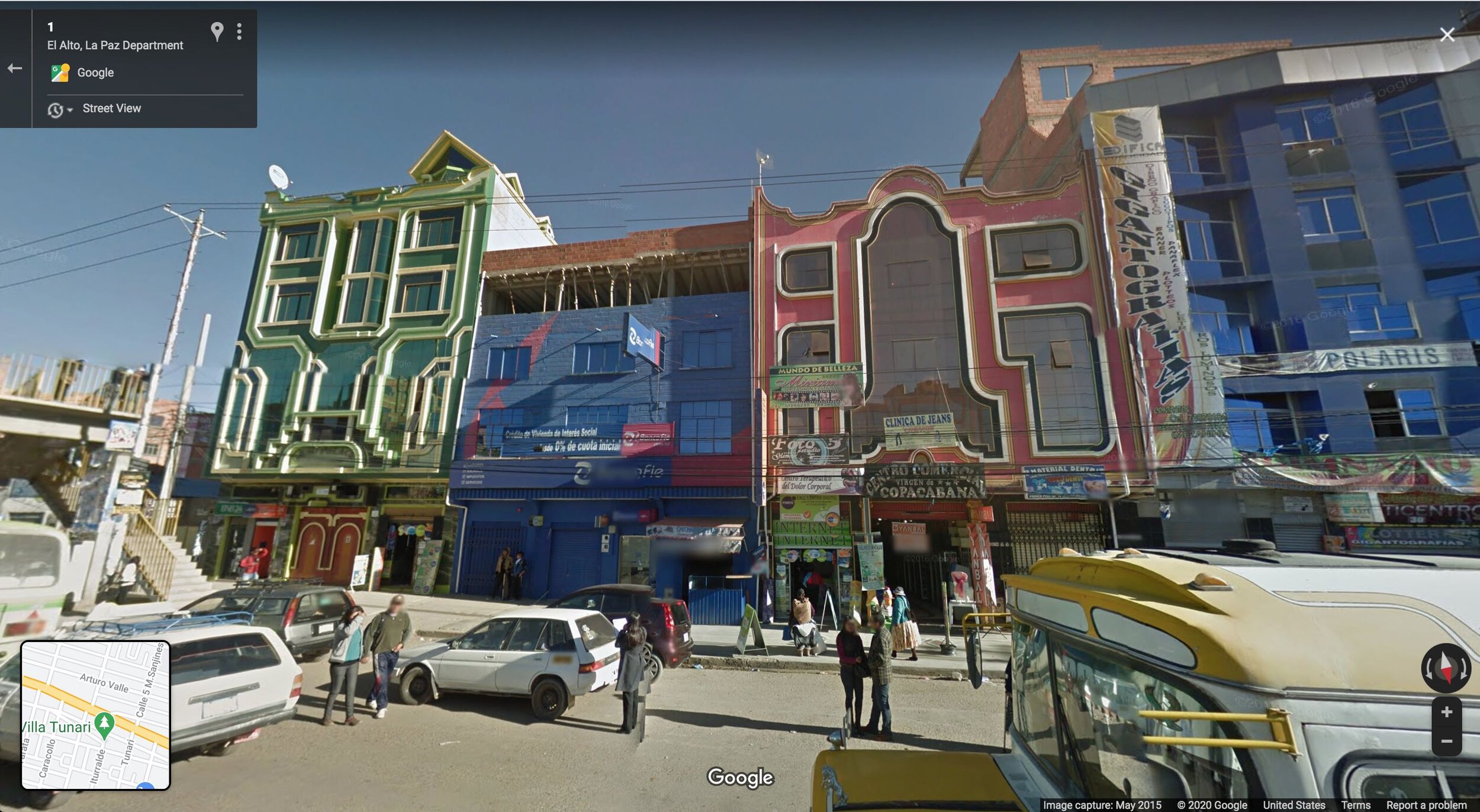

The productivity of the development pattern here begins to allow for things that you don’t see in the poorest outskirts, such as playful and experimental architecture. Here is the Neo-Andean style pioneered by Bolivian architect Freddy Mamani Silvestre: its technicolor aesthetics manage to simultaneously look space-age and celebrate the country’s indigenous Aymara heritage.

Below we see what the oldest, most developed part of El Alto looks like: its downtown. The hallmarks are higher quality buildings and lots of pedestrian activity and streetside commerce. This is the densest, “nicest” in terms of physical improvements, and richest part of town.

El Alto’s original reason for existence, of course, is La Paz. 440,000 people commute into La Paz every day, many of them on the Mi Teleférico aerial gondola, developed as the backbone of the region’s public transit system to avoid crushing congestion on the handful of winding roads down into the valley.

El Alto exists because La Paz, a much older city, developed enough intensity and productivity in its core that it was no longer economical for those with tiny budgets to settle there, so new arrivals to the city started to gravitate to El Alto instead. The core of La Paz, an established city for centuries, contains high-rise commercial buildings, elegant parks, and well-to-do residential areas.

Understand Why This is the Default

Bolivia is a vastly different country from the United States or Canada. And this is true in many ways that it would be beyond the scope of this article to delve into here. I’m certainly not writing this to suggest that Bolivia is somehow a model for the U.S. or Canada, or to present a simplistic caricature of La Paz and El Alto.

What I want to present is a basic pattern of development—unusually obvious and legible in a place like El Alto—that is in fact the historical and global norm. This is far more similar to what you would have seen in a U.S. city in the past—before the Suburban Experiment was underway—than today’s Americans are likely to realize. The details of architectural style and certain culturally specific aspects of land use and community design would be different. But the bar to entry to participate in physically growing the city—creating a modest home or shop—would have been very low, as it still is in El Alto. That gradient from bustling downtown to poor outskirts would have been there, as well as the phenomenon of poorer, newer settlements built to a sort of minimum viable standard, with the expectation that they will be improved later.

It’s that expectation, of a place that is ever-improving and never finished, that no longer exists under the suburban development model. And it’s worth contemplating what is lost with it. There’s something exciting about an El Alto, in all of its chaos and noise and perhaps lack of outward charm. And that something is the promise of improvement.

The Suburban Experiment has an 80-year head start on us, but there’s an increasing number of people who recognize the many things they can do to correct it. Join this growing cohort of change-makers by becoming a member today.