Defusing an Economy "Rigged to Blow"

Editor’s Note: Strong Towns member Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. This article was originally published on the Frontier Group blog. It’s reprinted here with permission.

The emergence of the novel coronavirus has been a shock to our health care system, our economic system, our communities, our relationships and our psyches. What makes some of those systems more able to absorb, respond and rebuild from shocks than others?

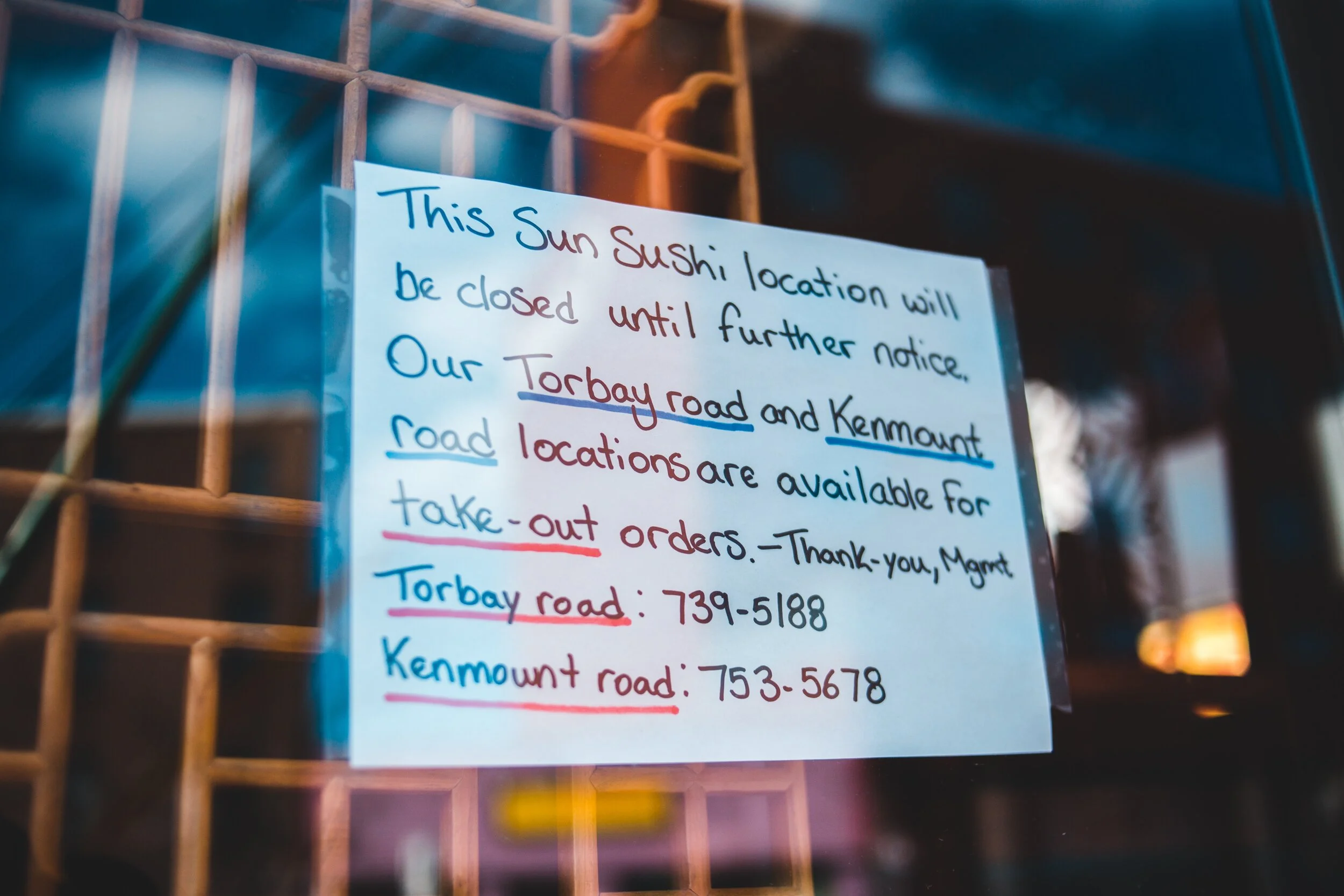

Two incidents last week got me thinking about that question. The first was a chance encounter with a friend on the street. He does residential construction work and, like many Americans, he is facing a sudden loss of income coupled with a looming rent payment on April 1.

He told me about a conversation he’d had with his landlord—the kind of potentially uncomfortable conversation that will be replicated by the millions in the days ahead. Expecting payment soon for a construction job, he told his landlord he’d be willing to pay for three months’ rent in advance, just to not have to worry about it. His landlord’s reply: Keep the money. The mortgage on the apartment had already been paid off and there would be time to settle up once the outbreak was over. Crisis averted.

The second incident was the debate over and passage of the coronavirus relief/rescue/bailout/stimulus bill. On paper, the bill would seem to alleviate crises like the ones facing my friend—offering extra time for certain student loan and mortgage borrowers. And it is just one of many efforts by local, state and federal governments, as well as private businesses, to give Americans a break on their financial obligations during the coronavirus crisis.

Not every borrower, however, is in a position to put up three months rent in advance—and not every lender is able to go without three months of rent payments. Moreover, when most of us deal with lenders we are dealing not with a person with whom we have a relationship but with an impersonal institution.

Image credit: Erik Mclean. Sun Sushi on Facebook.

Those institutions have financial obligations of their own. For example, while individual homeowners have relief on their loans, mortgage servicers—the middle-people who collect payments and pass them on to the ultimate holders of the loans—do not. Without extraordinary action, observers warn, the entire mortgage finance system could implode, sparking a new mortgage crisis just 12 years after the last.

The Federal Reserve is working to address that issue, along with the myriad other challenges now facing the economy. But there are concerns that its interventions in the mortgage market might have other unintended consequences that could lead to crises elsewhere.

It’s a mess.

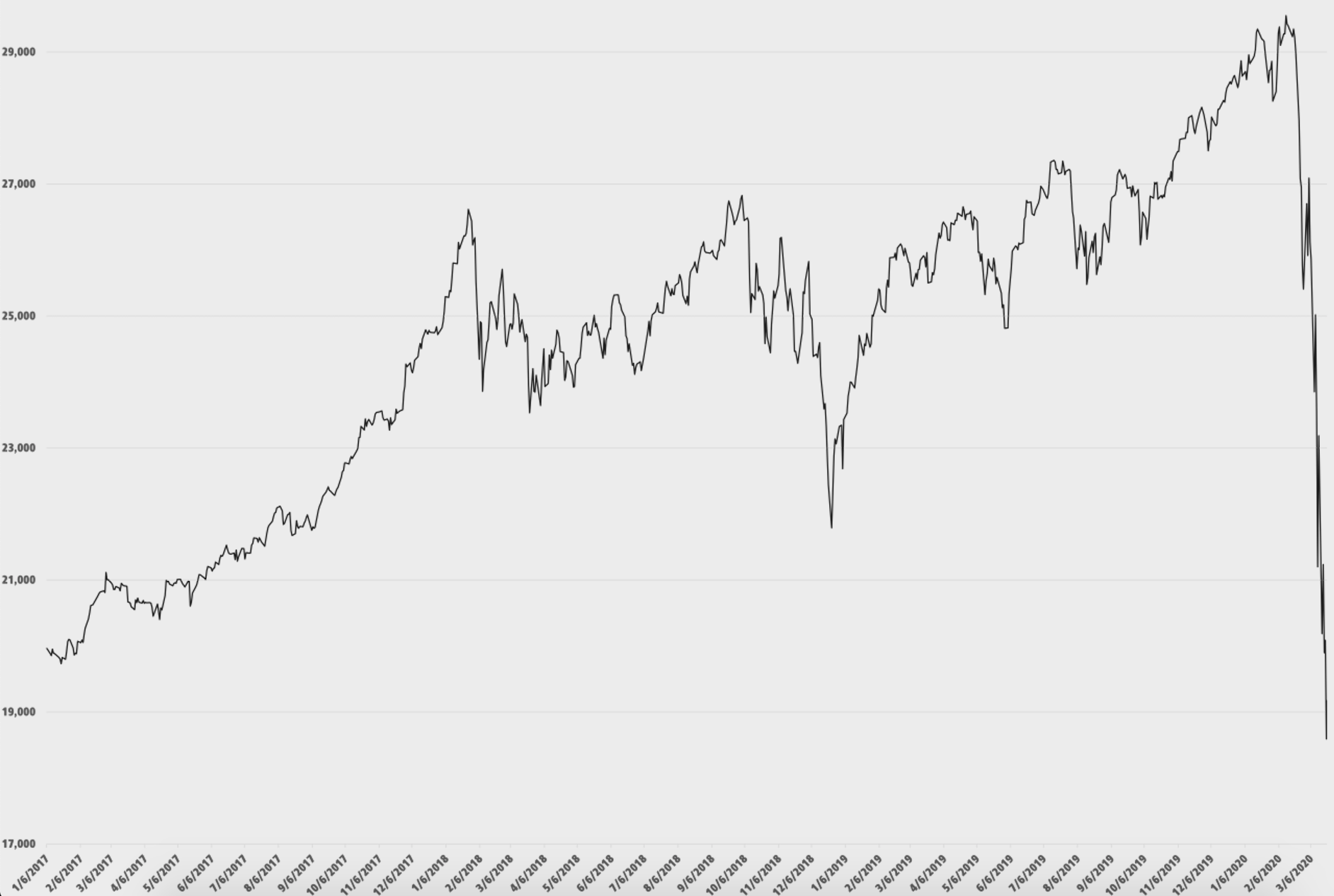

How is it possible that one of the most productive economies in the world, governed by some of the smartest people our country can muster, can lurch from seeming prosperity to full-bore crisis in just a couple of weeks? And for the second time in just over a decade?

The answer—and the pathway to a solution—might come from an understanding of technological disasters.

Multiplying threats; cascading failures

Imagine the Federal Reserve’s attempts to steer the economy through the COVID crisis as taking place in a giant control room, one with every single light flashing a dangerous red. Problems that emerge in one sector quickly bleed over to others. Seemingly sensible steps taken to address problems in one part of the system unexpectedly cause problems elsewhere. The operating manual—written to handle every imaginable malfunction—suddenly becomes useless.

There are terms to describe this kind of situation. Black swan. Cascading failure. And one that was popular during the financial crisis, and which takes on an eerie ring now: contagion.

Another less-well-known term, however, might give us useful insights into the crisis: normal accident.

I’ve written about normal accidents on this blog twice before: In 2010 during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and again in 2011 following the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Both disasters shared certain characteristics with one another—and with America’s current and recent financial crises.

In both the Deepwater Horizon disaster and the Fukushima meltdown, a single failure or precipitating event—a failure of cement at the base of the well in the case of Deepwater Horizon and a devastating earthquake/tsunami in the case of Fukushima—set off a chain of unexpected cascading failures that overwhelmed engineered safety systems and quickly blew through the system’s ability to adapt, leading to catastrophe.

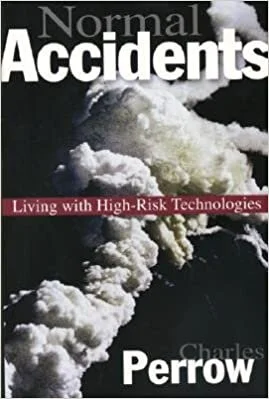

Charles Perrow, in his book Normal Accidents: Living with High Risk Technologies, theorizes that in complex, tightly coupled technological systems—like a nuclear power plant or a deepwater offshore oil platform—such accidents are inevitable, or “normal.”

Complex, interactive systems, Perrow argues, create vast numbers of potential pathways by which a single event can lead to systemic failure—so many that it is impossible to anticipate and plan for them all in advance. Moreover, the failsafes and other systems designed to prevent the failures we can anticipate have the potential to actually make things worse by adding even more complexity to the system.

When systems are “tightly coupled”—that is, when a change to one part of the system rapidly and inevitably causes changes in another—the potential for problems to spin out of control is magnified.

Let’s go back to my construction worker friend. His relationship with his landlord is loosely coupled. Because both he (a bachelor with few debts) and his landlord (who had already paid off his mortgage on the apartment) had financial slack, they had the space and flexibility to negotiate a mutually agreeable solution. Ruin for one did not necessarily and immediately translate into ruin for the other.

Image credit: Wikipedia.

Our modern financial system, however, is tightly coupled, as evidenced by the numerous temporary shocks to the financial system over the last couple of decades—known by names such as “Flash Crash” and “Flash Freeze”—in which glitches in individual systems operated by Wall Street firms quickly spiraled into cascading failures that affected global financial markets.

Tight coupling has advantages. It can be incredibly efficient. In good times, “slack” can look like waste (and sometimes is). But when it comes to adapting to challenges like coronavirus, tight coupling can be a big problem. Perrow writes: “Loosely coupled systems, whether for good or ill, can incorporate shocks and failures and pressures for change without destabilization. Tightly coupled systems will respond more quickly to these perturbations, but the response may be disastrous.” (emphasis added)

Rigged to blow: From viral to financial contagion

The effects of coronavirus are rapidly rippling through our tightly coupled, incomprehensibly complex financial and economic system—with potentially devastating effects to all of us.

One of the people who has been calling attention for years to the fragility of our current economic system is Chuck Marohn, founder of Strong Towns. In a tweet last week, Chuck wrote:

It's not the Main Street economy that is cratering. It is the financialized economy, which needs continuous growth and transactions to remain stable. Main Street is hurting, no doubt, but we can pull together and get through. Everything with securitized debt is rigged to blow.

I will take issue with Chuck on one thing: The Main Street economy and the finances of many American households are “rigged to blow”—in large part because of our exposure to debt. We have written about the growing exposure of American households to skyrocketing auto debt, but the same thing applies to student loan debt, commercial debt and credit card debt, not to mention mortgages.

Many Americans find themselves at this perilous moment piled high with debt and with precious little financial slack—while others who might have felt secure a couple of weeks are watching the flexibility they thought they had wash away in a tide of pink slips and vanishing 401(k)s. The ability that my friend and his landlord have to simply wait it out is not likely to be there for others—making the need for extraordinary measures of support from all aspects of society and all levels of government that much more acute.

Rebuilding resilience

So, what is to be done?

In the case of the current crisis, your guess is as good as mine. We are in truly uncharted territory. We can only hope that those in positions of policy-making are quick, imaginative and deft in their response—and that they avoid making errors that trigger unforeseen secondary disasters or that further entrench relationships that create more risk in the future. It won’t be easy.

In the long run, though, the current crisis calls upon us to build more resilience into our economy and our society; to build new structures so that even if a tightly coupled, highly complex global financial system does blow up, it doesn't take all of us with it.

This requires things like:

Rebuilding local economies;

Creating diverse, local supplies of goods and services;

Building and entrenching networks of mutual aid and care;

Ensuring that when essential tools or systems break, we have the knowledge and capacity to fix them;

Developing and deploying technologies and tools of self-reliance; and

Replacing a culture of immediate gratification and acquisitiveness with one of patience, gratitude and the ability to be satisfied with less. Leading, perhaps, to a reexamination of our relationship with debt.

All of these steps could be criticized as inefficient, or even “bad for the economy”—if your measure is one of goosing aggregate GDP growth for the next quarter. But if they enable us to ward off the kind of catastrophe that destroys lives and institutions and leaves massive and lasting scars, they will be worth it.

When it comes to a virus of either the medical or financial variety, the potential for damage is far reduced when the hosts—our bodies, our communities, our economies—are strong, resilient and flexible.

We have a lot of work to do.

About the Author

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S. and have earned coverage in outlets from National Public Radio to the Financial Times. He is the lead author of A New Way Forward and 50 Steps Toward Carbon-Free Transportation, which together lay out a vision and policy roadmap for decarbonizing America’s transportation system, as well as numerous other reports and white papers.

Prior to joining Frontier Group in 2001, Tony worked as an education reporter for the Eagle-Tribune newspaper of Lawrence, Mass. He also worked for six years as a political writer with the Fund for the Public Interest and for two years organizing college students on environmental issues in New Jersey. Tony holds a Master's degree in print journalism from Boston University and a Bachelor of Science in public service from Penn State University. A native of Pittsburgh, he now resides in Boston with his family.

Ilana Preuss is the founder and CEO of Recast City, a program that helps cities build strong downtowns by empowering small-scale manufacturers. Today, she joins host Tiffany Owens Reed to discuss the importance of small-scale manufacturing and her experiences as a city builder.