Everybody Loves Local Businesses Now. How Do We Make the Enthusiasm Last?

One of the more uplifting consequences I've witnessed of the current shutdown period has been an outpouring of support for small, locally-owned businesses in my community. Residents are coming together on social media and through word-of-mouth networks, exchanging recommendations and going out of our way to patronize vulnerable local shops and restaurants that we'd like to see outlast the novel coronavirus.

I wonder how long the current rally-round-the-entrepreneurs mood will persist—and what it would take to keep this surge of interest in buying local alive after shelter-in-place orders go away. And it's got me thinking a lot about the barriers to that interest in the first place: the relationship between us, our cities, and our mom-and-pop shops.

Don't get me wrong: Americans have always been in love with the idea of local business. It's deep in our cultural mythology of meritocracy, ambition, inventiveness, and grit: we tell ourselves we're an independent-minded people who build things. Politicians of all parties throw endless lip service to small business.

And yet in normal times, our actual relationship with local businesses is a lot less feel-good. We have built a financial system, a physical pattern of development and an approach to transportation that result in communities that are systematically hostile to the small entrepreneur. And as a result, we've become the land of Walmart, Amazon, Home Depot, and oh so many chain eateries.

There are a ton of reasons—which I likely don't have to convince you of if you're part of the Strong Towns movement—to want those trends to reverse. By re-localizing aspects of our economy, we can promote community cohesion, economic dynamism, financial resilience, and even public health—for generations to come. It's simply a huge step in building stronger places.

More reading from Strong Towns on the value of local economic self-reliance:

Import Replacement by Charles Marohn

Dunkin Our Future by Charles Marohn

How a Beloved Corner Store in South Los Angeles Addressed Food Deserts (Podcast)

Community Allies: The Virtue of Locally Owned Business by Bruce Nesmith

Small Businesses Can Save Your Community by Quint Studer

How a Local Bookstore Can Make Your Town Richer—In More Than One Way by Kea Wilson

Stacy Mitchell on the Big Box Swindle (Podcast)

2019 Ask-Me-Anything webcast with Stacy Mitchell of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance

Here are a few observations about how to understand this trend—if it is one:

1. Local pride of place is a powerful force—and crises bring it out in a lot more people.

Think of it as a sort of patriotism, but oriented toward your immediate city or even neighborhood, not your country at large. I'm seeing this phenomenon I've never heard talk in such terms before, and I think it's a good trend. (Especially in a place like the one I live, Southwest Florida, where few have deep roots. The first question you ask when you meet someone new in Florida is "Where are you from?")

Civic pride is one key motivator for the longtime buy-local crowd—and I count myself in that number, though I'm not as diligent about it as I would like to be. It's important to me to live in a place that has some there there, that is fundamentally unlike other places. I think it binds us together with common purpose and creates bonds of trust and solidarity among relative strangers that end up mattering when crisis strikes. So when I can, I'd rather hand over cash to a neighbor who runs her own shop than swipe a credit card to pay a multinational corporation. For a simpler reason, too: the smiles and words exchanged in that neighborly transaction have the capacity to brighten my mood for hours.

My hope is that a whole slew of people become exposed to that feeling of connectedness and rootedness for the first time in the present moment, and find it reassuring enough to want to hold on to it.

2. When forced to slow down, we start seeing what was always there.

Our whole post-WWII development pattern is designed so that you would never stumble upon a great small business accidentally—some of the best local establishments are buried in strip malls you whiz by on stroads at 45 miles per hour. Under normal circumstances, a mom-and-pop shop faces huge headwinds in this environment: drivers will usually only opt to pull over and park for the tried-and-true of a familiar brand.

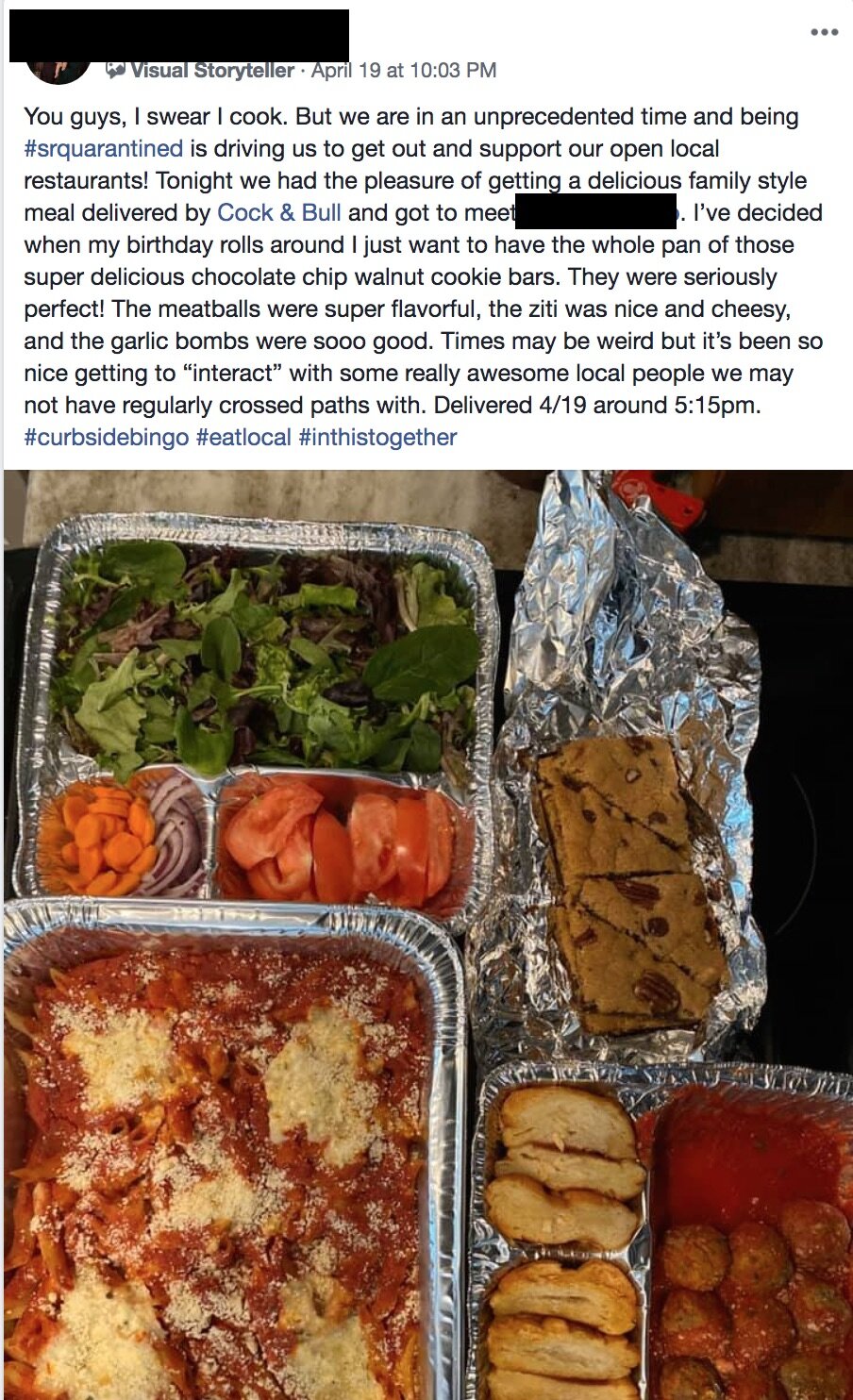

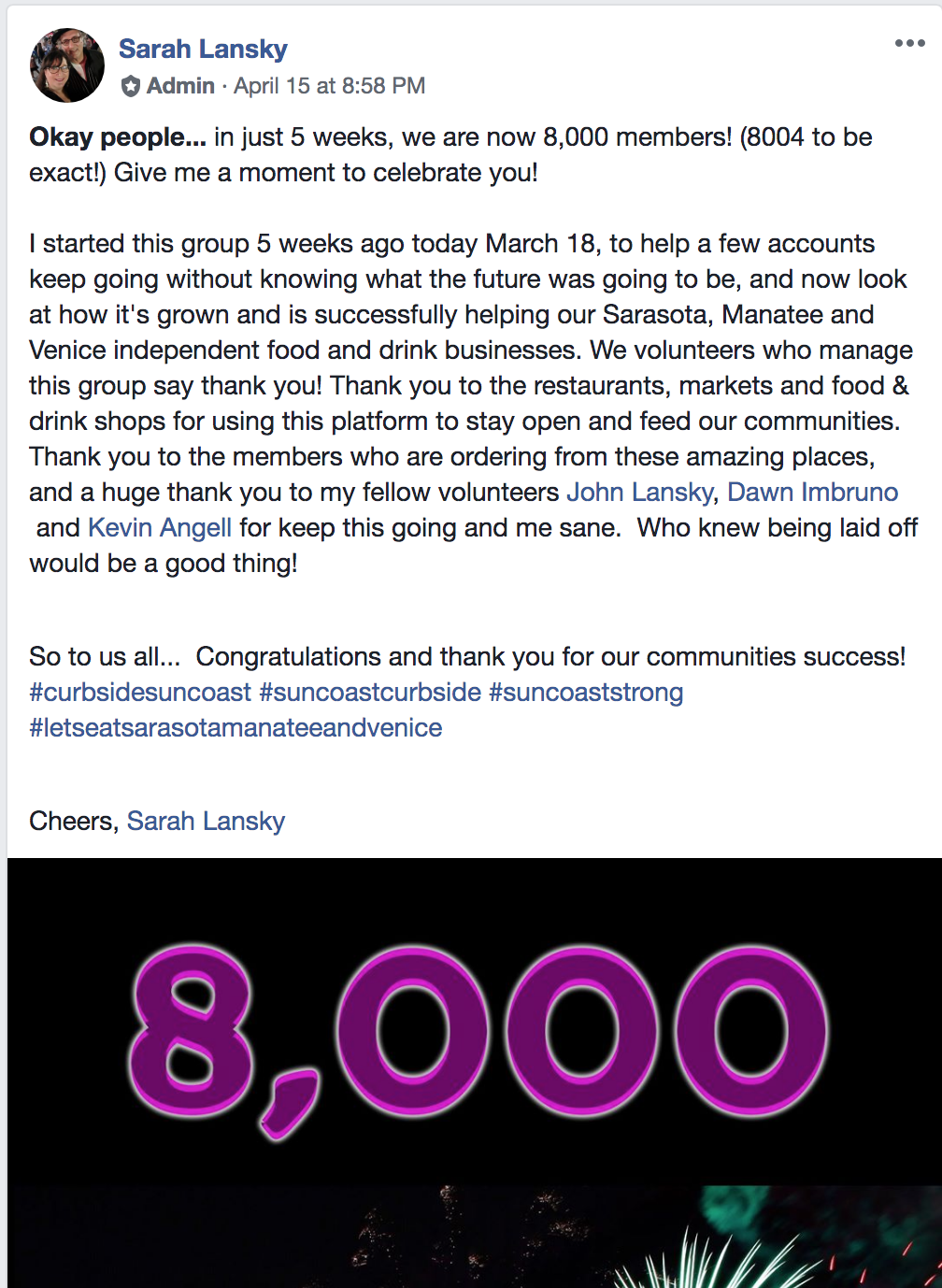

Until, that is, we're not all just on the go all the time, and we get more deliberate about where we want to spend our dollars. Where I live, a Facebook group popped up for "Suncoast Curbside & To-Go" around the time businesses started closing down. It now has roughly 10,000 members, and the group is buzzing with activity at all hours of the day: not just restaurant recommendations, but every sort of local alternative to corporate chains. People are asking about butcher shops they can support instead of buying meat from the supermarket; fresh milk, eggs, and produce from nearby farmers; one thread even discusses "the guy in a shack on 15th" who will sell you fresh blue crabs if you text him in advance. People are asking questions and advising each other on things such as how much to tip delivery workers (consensus answer: a lot, if you can—I'm seeing 20 to 50 percent). There's even a popular “Curbside Bingo" game underway.

It's genuinely exciting to peruse this group, even as I think we all soberly recognize that it exists because hundreds of businesses in our community fear for their survival right now. I've found out about a dozen businesses I had no idea existed that I plan to patronize, now or even well after shutdowns are a thing of the past.

3. We behave more deliberately when jolted out of our routines.

Crises are moments of opportunity because of basic human psychology: we are creatures of habit, until we're forced not to be. Our minds are wired to do most things on auto-pilot, except when we can't because the context is new. It's the reason the best time to join a gym is when you've just started a new job or moved to a new house—you can incorporate it into a brand new, not-yet-autopilot schedule and commute in a way that may stick.

Click image to view larger: advice from our friends at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Good advice, but not enough if we don’t also reform our development pattern.

The Facebook group I described above could have been created in any other month of any year (minus the "curbside" / "to-go" aspect, but certainly as a recommendation group for local food and drink businesses). It would not have exploded the way it has.

Something like looking for a local butcher to buy meat from was a conscious choice for a number of the members of this group, motivated by the desire to do the right thing in a moment where every small action feels freighted with moral consequence. Hopefully continuing to shop at that butcher instead of going to Publix becomes the new autopilot routine for at least a few of them.

This is important since none of us are capable of keeping up that feeling of deep contemplation of the morality of our day-to-day actions for very long. We would simply burn out.

4. Personal change is still no substitute for structural change.

That last observation—that humans do most things on autopilot and relatively few things as conscious, considered decisions—means that people in general will still follow the path of least resistance set out by the incentives and structures they face.

I'm all for encouraging buy-local movements and localist ethics, but at the end of the day, we need to reform the way we structure our communities so we're no longer stacking the deck against the neighborhood butcher shop, the food truck proprietor, the local farmer.

Strong Towns founder Chuck Marohn has written about how the physical development pattern pioneered in the suburban era constitutes a huge source of subsidy for large chain businesses. Wide roads built to accommodate the turning radius of an 18-wheeler; arterials feeding into freeways at high speed; exorbitant requirements for parking, landscaping, and signage; all of these things favor the streamlined supply chain and top-down hierarchy of a chain, and all but guarantee that the chain business will have an easier time a) grabbing your attention, and b) offering you a competitive price on its product or service.

When our local governments set the bar to entry to being a local entrepreneur too high—for example, by not allowing food trucks or pop-up shops, or by imposing irrational and excessive permitting requirements—we also stack the deck in favor of national and international conglomerates instead.

It would be easy to look at the resulting landscape of chains, chains, and more chains and conclude that it's simply the market at work: this must be the world consumers want. But, you see, I can point you to a local Facebook group going on 10,000 members who would tell you otherwise. The coronavirus economy is revealing to us that countless people love local businesses, even in places not known for hometown pride, and even in places where the physical environment—high-speed roads, big parking lots, and a lack of neighborhood-oriented or mixed-use business districts—is hostile to a small independent business’s survival.

We just need to make supporting them—the right thing to do for many reasons—also the easy thing to do, not just in the current crisis but always.