How a Student-Created Co-Living House Broke the Law Then Changed the Law

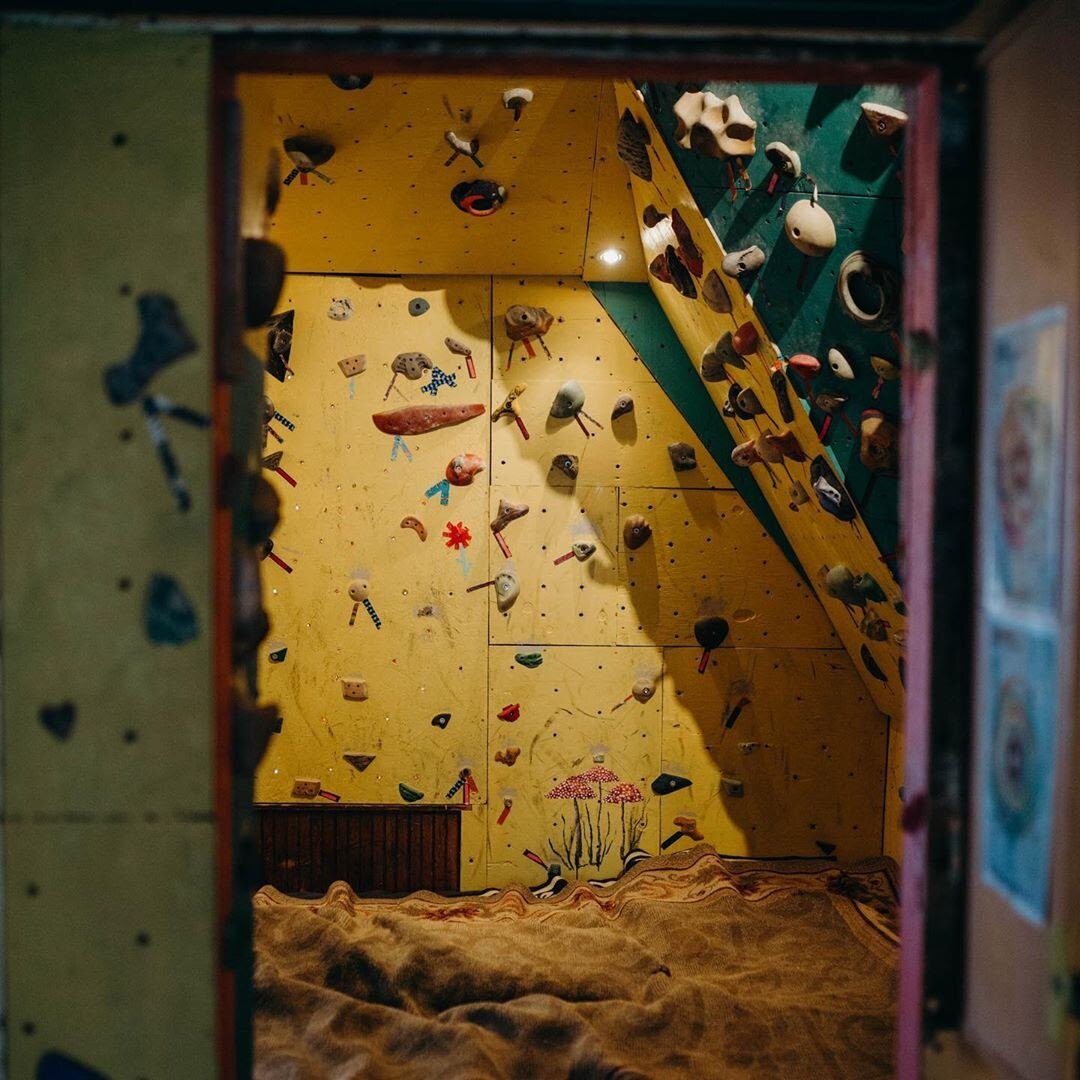

Photo source: Marquette Climbers’ Cooperative

The Marquette Climbers’ Cooperative (MCC) is Marquette, Michigan’s first official housing cooperative. It’s no coincidence: they helped design the new legislation in order to keep operating.

Zoning Ordinance, 54.202(68)(b)

Marquette is a quaint college town along the shore of Lake Superior that is overflowing with craft breweries, artisanal brunch spots, and late-night cafes. The streets splinter out from the banks of the world's largest freshwater reservoir, slanting upwards towards the campus of Northern Michigan University (NMU). Situated on the corner of N 4th. and Ridge St., about a 10 minute walk from the Lower Harbor Ore Dock, sits an unassuming old Victorian that set a precedent for future housing options.

While co-living spaces—intentional communities that provide shared housing—are common in other university cities in Michigan, such as Ann Arbor and Grand Rapids, existing laws in Marquette limited residents to no more than four unrelated people living in a single family unit.

“Zoning ordinance, 54.202(68)(b) from the Marquette's Land Development Code,” says Ian Girard, who helped establish the MCC in 2012, referencing the city code that hindered the establishment of the co-op.

For Girard and the household members, opening and operating the unofficial cooperative would be training towards changing the law to make it official.

Photo source: Marquette Climbers’ Cooperative

From Climbing to Cooperative

When Girard first hatched the idea in 2012, he couldn’t sleep for three days.

“I was too excited,” he recalls. Though he wasn’t fixated on typical undergraduate concerns.

“I fantasized about a collective of student climbers coming together to take on the responsibilities of sustainable homeownership. I pondered lessons from social psychology [and] pit theories of community against diffusion of responsibility,” he wrote on the house's blog in 2017.

The MCC began as a co-living home and community-accessible bouldering wall for climbers and non-climbers alike. A core feature of the house is fostering leadership among its residents through shared equity and individual responsibility. As a cooperative, each member has an equal vote in determining how the organization is run, ideally towards the greater good of all the members.

There are clearly established rules, bylaws, goals, and objectives, with a focus on sustainability. Early projects included building a greenhouse, planting fruit trees and vegetable gardens, and investing in energy efficient appliances. They collectively manage everything from their shared budget to hosting community events.

Photo source: Marquette Climbers’ Cooperative

Founding members, many of which were NMU students, saw the benefits of a cooperative model, from lower cost of living—housing six to eight people instead of four, for example—to the real world lessons that come from homeownership.

And of course, they wanted space for an indoor bouldering wall too. That is, a low height artificial rock wall which uses soft pads for protection rather than ropes.

While summers in Marquette are known for idyllic beauty, the ice season is brutally long with 73 days that reach a maximum temperature of freezing.

“We joke that we have Fall Semester and Winter Semester,” shares Bryce DeMers, a senior Biology major at NMU and the current President. “Winter goes until May.” Hence, the need for a bouldering wall inside.

Unfortunately, the venture was on shaky grounds from the onset.

“Somebody at the city had a bone to pick, or something.”

In order for members of the house to feel secure in the dwelling, they needed to know they could keep living there.

“A home needs to reduce the stress as much as possible in order for its members to focus on larger goals,” says Girard. “But whenever we got a cease and desist letter, we’d be worried about whether the project could even continue.”

Despite the threats, the residents could not be evicted due to the Michigan Constitution superseding local regulations. This explains how the members were able to operate for seven years without incident. But, they didn’t know that at the time.

Rather than try to adhere to regulations, house members decided to try and change the code, a perfect encapsulation of what the co-living space is about.

Advocating for Change

Photo source: Marquette Climbers’ Cooperative

The city had some concerns. Co-living spaces are historically associated with fraternity and sorority houses, arrangements which can lead to property damage and noise issues for neighborhood residents.

“There’s always a delicate balance between the individual or small group within the context of the larger community,” shares Girard. “It’s not just a cooperative problem, it’s a problem many businesses and affordable housing projects face too.”

House members spoke with neighbors, the larger district, and town councilors to work towards consensus.

“It took a couple of years to get enough backing to support the idea and craft the language for the new article,” says DeMers.

They pushed for a definition of “intentional community,” which is now defined in Section 54.614 of the Marquette Land Development code as: “A planned residential community designed to have a high degree of social cohesion. The members of an intentional community typically have common interests, which may be an organizing factor, such as a social, religious, or spiritual philosophy, and are likely to share responsibilities and resources.”

“By going the official route, we could be as ‘loud’ as we wanted in advocating for the idea,” reasons Girard. “We wanted to make it easier for more cooperatives in the future. [Thinking that] if there’s a template that works, it encourages other co-ops to form."

New legislation was adopted by Marquette on Feb. 11, 2019. On March 17 of 2020, the MCC was accepted as the city’s first official housing cooperative.

The MCC’s focus on cooperation proved its mettle, the intention all along.

About the Author

Aaron Gerry is a freelance writer focused on emerging communities, rural development, the impact of adventure tourism, and cultural trends in climbing. You can read more of his work at aarongerry.com.

In this episode, Chuck explores the flawed nature of North America’s current “housing bargain,” where most neighborhoods are allowed to stay exactly the same as long as some neighborhoods are forced to radically change. (Transcript included.)