What COVID-19 Teaches Us About How to Fix Freeways

Strong Towns member Joe Cortright runs the think tank and blog City Observatory, where this article first appeared.

As everyone knows, traffic is moving much faster today than six weeks ago. Stay-at-home policies have reduced car travel by more than half in most of the nation’s large metro areas.

The pandemic traffic miracle: Freeways are carrying more cars, faster

With lower traffic volumes, cars are zooming along, with most freeway traffic in Portland, Oregon regularly exceeding the posted legal speed limit.

So you might think that our freeways are carrying fewer cars at the peak hour than six weeks ago. But you’d be wrong. Actually, at the peak hour, between 4:30 and 5:30 PM, major Portland-area freeways are carrying just as many cars now (actually slightly more) than they were pre-COVID-19. And they’re going much, much faster.

Let’s take a close look at I-5 through North Portland, reputedly one of the most congested roadways in the state (and a place where the Oregon Department of Transportation wants to spent upwards of a billion dollars to widen a mile and a half of roadway).

We look at the area between the Rose Quarter and the Interstate Bridge (milepost 300 to milepost 309). We pull together real-time traffic speed and volume data recorded by Portland State University’s PORTAL traffic counting program. PORTAL measures traffic speeds and volumes. We look at peak hour travel volumes and speeds on weekdays, Northbound, between 4:30 and 5:30 PM between the Marquam Bridge (Milepost 300) and the Interstate Bridge (Milepost 308).

Let’s first look at the baseline: What is traffic like on I-5 on a typical weekday? We focus on the afternoon commute because its generally the worst and most regular traffic tie up. Here’s the Portal data for I-5 for the five weeks prior to the implementation of social distancing measures, from February 3 to March 12, 2020. On a typical weekday, this stretch of freeway carried about 26,900 cars during this hour at an average speed of 25.6 miles per hour.

Now look at the post-COVID period. Here are the data from March 13 to March 28. To no one’s surprise, speeds are up, to an average of 53.6 miles per hour (on a stretch of freeway that is posted with a 50 mile per hour speed limit). And the peak hour volume, from 4:30 PM to 5:30 PM: It is 27,450 vehicles in this hour, not down, but up, about 2 percent from pre-COVID levels.

Post-COVID-19: Speeds are up on I-5, and so is peak hour traffic volume

The simple but seemingly amazing fact is that the I-5 freeway is carrying more vehicles, faster, now at the peak hour than it did prior to COVID-19 travel restrictions. How can this possibly be the case?

What highway engineers know, but won’t tell you about congestion

It’s actually a well known fact that roads carry more traffic, faster, when they’re not allowed to become congested. Freeways are subject to a kind of “tipping point”—they carry more and more traffic at reasonably high speeds (45-50 miles per hour) right up to a point where traffic flow becomes saturated, and one minor slowdown is rapidly propagated through the system, and the road declines in speed and—this is the important part—it loses capacity: it actually carries fewer cars.

The reason that I-5 was so jammed up before the COVID-19 pandemic, and is so fast-moving now (and carrying even more vehicles), is entirely explained by the fact that we’ve kept traffic below that tipping point. Here’s the data from PORTAL that shows, before and after, how this works.

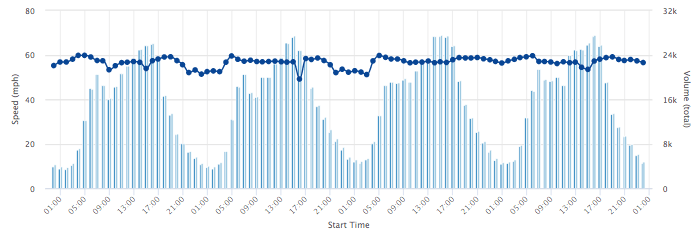

BEFORE: Tipping point hit at 2-3 PM, and speed falls until 6-7PM. This is exactly the phenomenon we see on a daily basis on I-5. Here’s a chart of typical daily traffic volumes from Midnight (0 hour) through the entire course of the day. These data are for I-5 Northbound from milepost 300 to 307, from February 10 to February 14. The blue lines correspond to speed (measured on the left axis); the blue columns are traffic volumes, per hour, measured on the right axis).

As you can see, at about 2 pm or 3 pm everyday, traffic volumes on I-5 North reach the saturation level, and travel speeds fall sharply to around 20 miles per hour. They stay that way usually until between 6pm and 7pm, when traffic volumes fall enough (fewer cars and trucks entering from the South) to allow traffic to accelerate back up the the speed limit.

AFTER: Traffic stays below the tipping point all day; speed averages 55-60 miles per hour all day. This is the same chart as before, for the dates April 13-17.

Because the freeway never becomes saturated and doesn’t push past its tipping point, travel speeds stay high—and the road carries even more traffic at the peak hour (between 4:30 and 5:30 PM) than it did prior to the pandemic.

Notice that while peak hour volumes are up slightly, total daily traffic counts are, in fact, down. Here we look at 24-hour traffic counts for milepost 307.9. For the weekdays from February 17 through February 28, this stretch of I-5 Northbound averaged about 46,700 vehicles per day. For weekdays of the week March 23 to 27, traffic volumes had declined to about 38,100 vehicles per day, a decline of about 18 percent. What this almost one-fifth decline in traffic meant was that at no point during the day did the volume of traffic push the freeway past its usual “tipping point” that triggers congestion and prolonged slowdowns.

How is that possible? The science of freeways and congestion

Here’s the way freeways really work: As long as everyone is moving at 45-50 miles per hour, the freeway works well, as it carries the maximum amount of traffic. But once a freeway becomes even slightly overloaded, traffic speeds fall abruptly, and—this is critical—the freeway actually loses capacity (i.e., it carries fewer cars past a given point at any period of time).

The relationship between traffic volume and traffic-speed is nonlinear. When we chart traffic speeds against volumes, we get a curve showing how traffic jams form. Here’s an example from the Washington State Department of Transportation’s 2018 Congestion Report. Speed is shown on the vertical axis; the volume of cars on trucks on the horizontal axis. Each dot corresponds to an observation of the number and speed of cars on this section of roadway. The shaded curve shows the statistical relationship fitted to the pattern of dots.

At low levels of volume (top left), traffic moves a long at a free flow speed (usually the speed limit, or slightly higher). As traffic volumes increase (moving along that curve to the right), speeds decline slowly. Once traffic becomes saturated—on this chart, between 1,500 and 2,000 vehicles per lane, per hour—we get to a point of instability, where the speed/volume relationship is erratic and the curve becomes backward bending. The exact tipping point for any stretch of freeway will depend on a number of factors: whether the road is straight or curved, the presence of on- and off-ramps, and other factors. Once a road reaches and slightly exceeds its capacity, traffic suddenly slows, and the road then carries fewer cars. The roadway tends to stay stuck in this lower part of the curve until traffic entering the freeway drops, and cars can accelerate and get to the upper part of the curve.

The reason we have recurring traffic jams is because there’s nothing to stop too many cars from getting on the freeway, and once they do, and push the freeway past its tipping point, the roadway tends to stay congested. In fact, a lot of the “improvements” that highway engineers make (i.e. expanding the capacity of ramps), actually makes it easier for more cars to get onto the roadway, causing it to jam up sooner. (As we documented at City Observatory, the widening of I-5 at Victory Boulevard a decade ago was associated with lower throughput over the I-5 bridges at the peak hour).

That’s why “removing bottlenecks” is a hopeless game of infinite whack-a-mole. When you enable more cars to travel faster at one point, you simply overload the next downstream point even more quickly, and the traffic jams recur. It’s one of the reasons that widening freeways never reduces congestion…even when you have 23 lanes of freeway, as in Houston.

So the trick in making a freeway maximize its throughput is to keep traffic levels just below this tipping point. And that’s exactly what the COVID-19 travel restrictions have done on freeways throughout the nation. (It’s draconian and inefficient to be sure, but it shows how managing demand can make congestion disappear).

Policy implications: Managing demand is the key to reducing congestion

The experience of the past few weeks should be a powerful object lesson in how to effectively fight traffic congestion. If we manage demand for the roadways at the peak hour to keep traffic volumes below the tipping point, we can get our existing roadways to carry even more traffic than they do now at speeds right up to (and even above) posted speed limits.

You’d think with this revelation in hand, highway departments—especially cash-strapped ones, like ODOT, that face a 20-30% decline in gas tax revenues—would be looking to figure out how to apply the demand management solution so aptly demonstrated here on a daily basis. And remember, this doesn’t mean a dramatic reduction in total traffic, it just means keeping the volume at any one time from exceeding the freeways carrying capacity.

But what we hear from ODOT is just the sound of more bulldozers. Even in the face of demonstrable evidence about how to solve congestion without spending a dime on concrete or asphalt, they’re ready to march forward with a billion dollar freeway widening project on I-5 at the Rose Quarter—one, which without pricing or other demand management will simply increase congestion and pollution.

What this really shows is that their protestations to the contrary, highway engineers actually don’t give a damn about traffic congestion. Who builds a multi-billion dollar capital asset and then does nothing at all to manage its use, and in fact, allows it to regularly become monumentally inefficient by being overwhelmed by demand on a daily basis? A whole range of measures are available to traffic engineers, if they chose, to make the system work more smoothly, and deliver a better experience for all users. As economists have long pointed out, even a modest price for using the roadway at the peak hour would prompt some users to defer trips, take other modes, or take other routes, and would actually increase our well-being.

Congestion Pricing: What the COVID-19 traffic experience demonstrates is that pricing the roadway would not be an additional cost for road users, but rather it would generate huge benefits in terms of faster travel and better utilization of the roadway. It’s a powerful argument for road pricing. A system of time-varying tolls for the freeway system would encourage some people to re-arrange their trip-taking in a way that always kept the freeway from exceeding its tipping point. In this way, pricing provides what the British call “value for money”—if you pay a peak hour charge, you get a road system that works better for you and everyone else.

Managing Demand: Pricing may be the best and most powerful tool for making roads efficient, but it’s far from the only one. Every freeway in the Portland region is, by definition “limited access.” Most freeway ramps here have “ramp meters”—traffic signals that restrict the number of cars that can get on the freeway. The logic of ramp metering is drawn from the same underlying observations about the unstable, non-linear speed volume relationship shown above. Ramp meters are designed to keep too many cars from crowding onto the freeway all at once and producing these jams. But most ramp metering is timid, with fixed intervals (one vehicle every 5-10 seconds, regardless of how backed up or free-flowing the freeway is). Tougher metering, including allowing traffic to back up on on-ramps in order to keep the freeway moving, would produce higher levels of traffic flow). Likewise, the highway agency could consider simply closing some ramps at the peak hour. One logical candidate is the I-5 Jantzen Beach on-ramp to Northbound I-5. This short, substandard ramp essentially lets traffic from the Jantzen Beach shopping center clog up the flow of traffic onto the I-5 bridges and is a major source of the initial delays that trigger daily slowdowns. It’s also no coincidence that the improvement in I-5 traffic conditions coincides with the big decline in shopping trips to Jantzen Beach.

Here, in the midst of he COVID-19 pandemic, is an illuminating natural experiment that shows how, with a little ingenuity in the form of demand management, we could make our transportation system work much better—both relieving the annoyance of daily congestion, and providing even more throughput on our expensive infrastructure. If we’re smart, we’ll learn from this experiment and choose to manage our road system in a way that provides benefits for everyone, rather than simply throwing more billions at wasteful road-widening projects that do nothing to resolve the fundamental cause of traffic congestion.