A Love Letter to the Slums: The Urbanism of Final Fantasy 7

We can learn a surprising amount about cities from fiction. By telling the story of an imagined place, a work of fiction has the power to expose or call into question our ingrained cultural values and narratives about real places as well.

I'm no huge gamer, but I am just the right age for the classic 1997 role-playing game Final Fantasy 7 to have been a formative experience for me. So I've been eagerly awaiting the long-delayed PS4 remake with bated breath... and more bated breath... and yup, still bated. But the first installment is (finally!) here, and one thing I'm loving about it is the game's unique urban setting, now rendered in stunning detail.

While plenty of video games either feature grand, picturesque cities to explore, or are set in bleak sci-fi futurescapes, FF7 offers something more unusual: a huge chunk of the story takes place in an urban slum.

Lessons From the "Informal" City

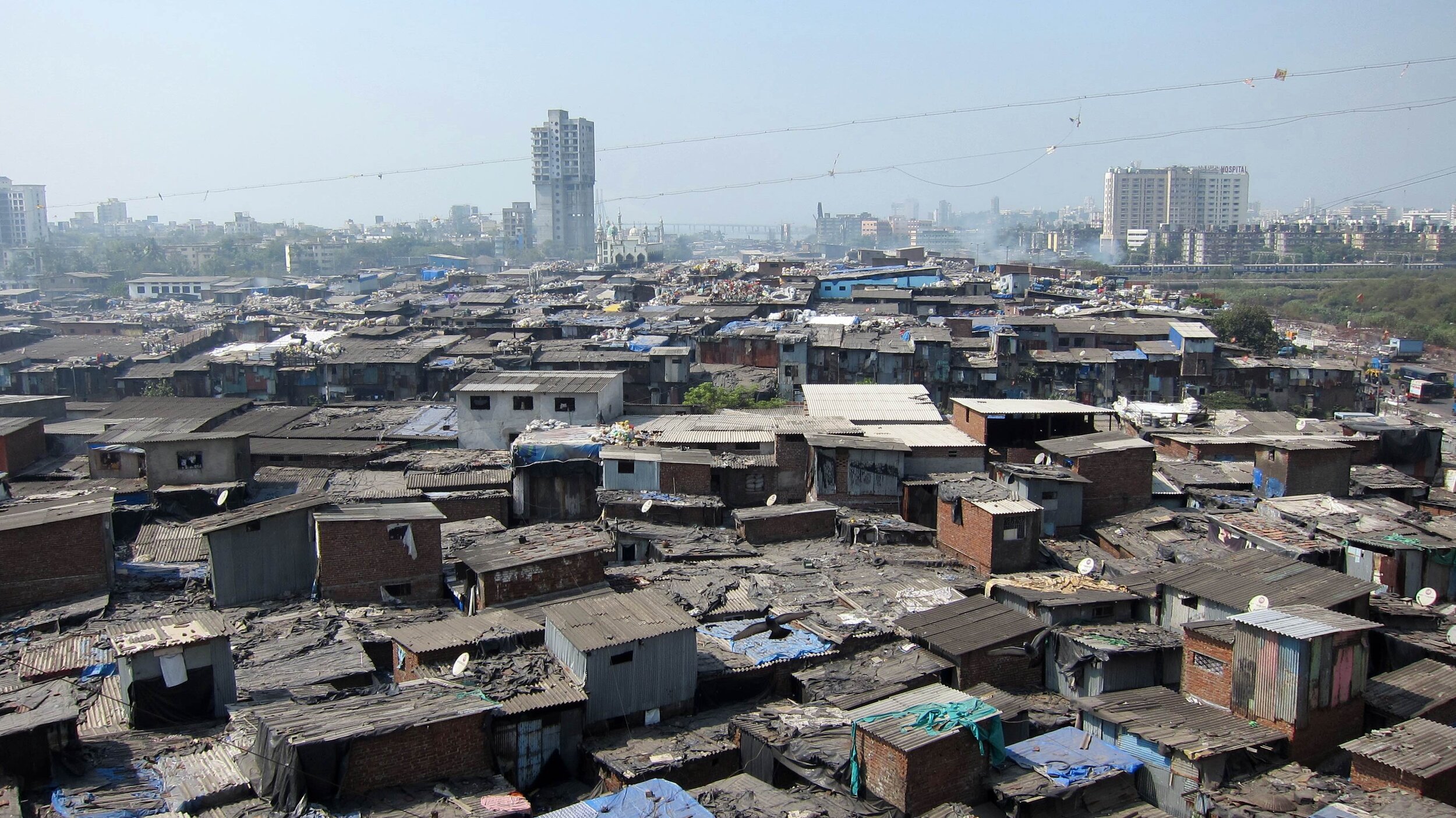

Specifically, FF7's slums appear to me to be inspired by real-life precedents such as Dharavi in India, Soweto in South Africa, Brazil's famous favelas, or Hong Kong's Kowloon Walled City, demolished in the 1990s. These are the kinds of places urban planners and economists refer to as "informal settlements"—meaning that their development is largely unplanned and unregulated. Much of the economic activity within them may occur on the unregulated black market as well.

Informal settlements in the real world are places of poverty, yes, and often overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, crime, and unreliable utilities and services. This is true. What is also true, though, and less often depicted in popular culture, is that they are places of tremendous resourcefulness and scrappy invention, and whose residents have every bit as much pride of place as the owners of a row of historic mansions. Maybe more.

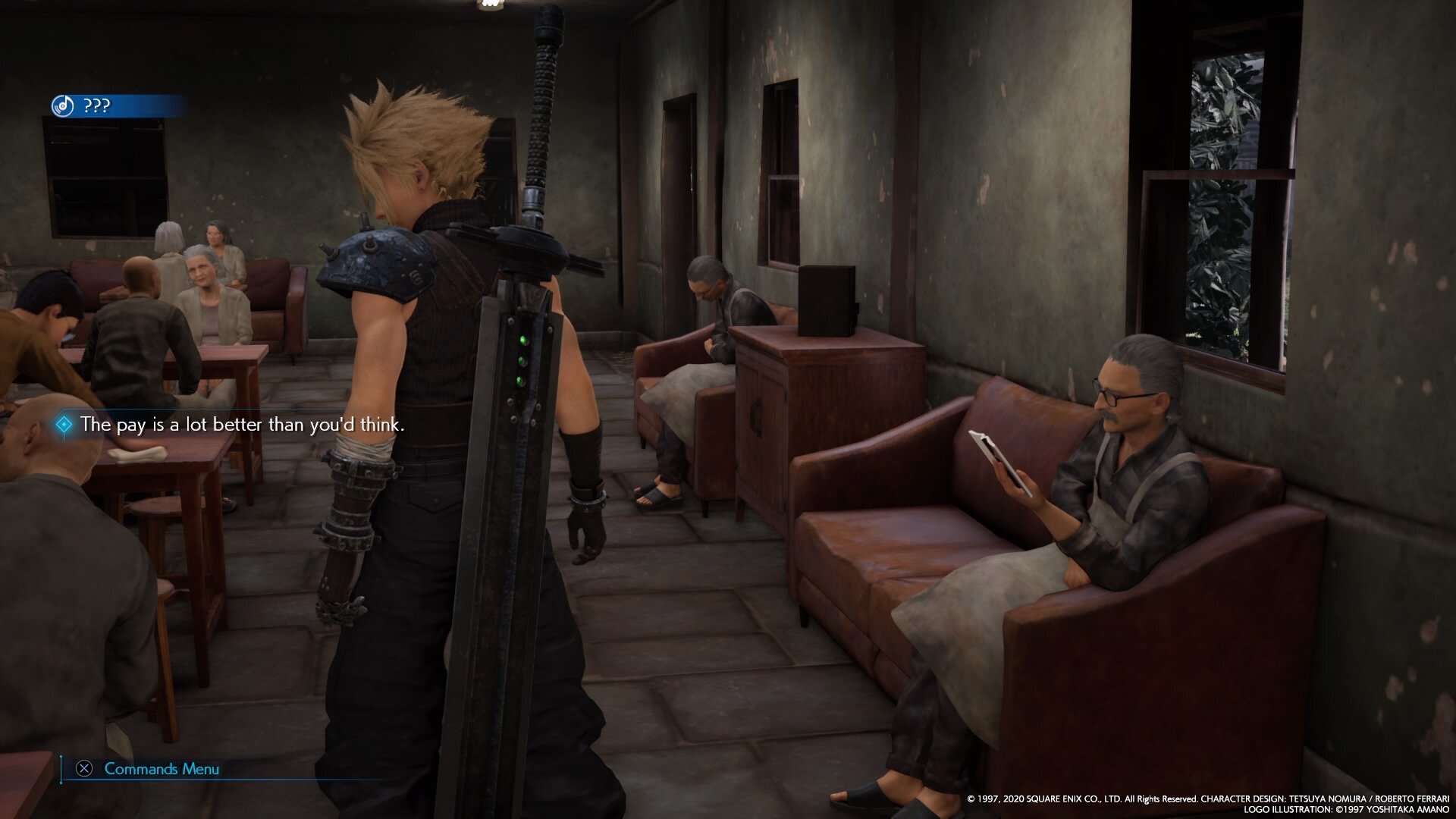

The heroes of FF7 are slum dwellers, and the emphasis as you explore their home is not on squalor or poverty or even oppression (though the presence of those things is made clear) but on the richness of community, resilience in the face of adversity, and the often heroic bootstrapping efforts of the inhabitants.

Slums Illustrate the Traditional Development Process

An informal community is a sort of proto-city, in which residents build what they can with what they have, and then constantly work to improve on it incrementally over time. This is, in fact, the only way you build a place when you have a) very limited resources to draw on, and b) no ability to take on large amounts of debt. Note that these conditions describe nearly all human settlements before the 20th century—it's only in the very recent past that we begin to see the anomaly of places planned and built all at once to a finished state.

Put another way, New York City started as what we might today presume to be a "slum"—a collection of makeshift shacks. So did London. So did Tokyo. So, almost certainly, did wherever it is you live, if it existed much before the 20th century.

The developers of Final Fantasy 7 took an obvious interest in how people would actually live in the game's environment, not just making it look cool. As The Verge reports in an interview:

[Co-director Naoki] Hamaguchi says that the team didn’t start from the perspective of changing the original city; rather, they wanted to expand it in a way that made sense. That meant not only making areas larger and denser, but also thinking about how they functioned. In the Sector 7 slums, for instance, a focal point is the 7th Heaven bar, the home base for environmental activist group Avalanche. The bar is huge, one of the largest structures in the sector, and a number of smaller businesses extend from there, including a vibrant street food district, small-scale apartments, and other essentials like a general store and weapon shop.

The result is a place that feels real and lived-in in small, frequently captivating ways. It's clearly expressed that we are exploring a makeshift environment meant as a temporary stepping stone to something better:

There is a mix of temporary, improvised structures and much higher-quality and more permanent ones.

Ad hoc placemaking using found materials is common.

The most impressive structures and the greatest hubs of activity are at the geographic center of the community (which is presumably where land value is highest).

Many of these centrally-located buildings are "third places," which play an important role in the social life of the community. (These are establishments like bars and restaurants, and a community center where, we're told, the old folks hang out just to talk.)

There’s a clear, defined main street where commercial activity is concentrated. The biggest difference between this and a mature city has to do with the quality and permanence of the structures, which get upgraded over time—not the basic function or layout. Otherwise, the basic pattern of what we would recognize as a neighborhood main street in a well-to-do modern city is there.

The streets themselves are platforms for social and economic activity, much more than they are ways to move traffic. Much of life is lived in public.

Street vendors are ubiquitous: being unable to afford a storefront is no barrier to being a small entrepreneur.

The game also takes pains to flesh out the social environment of the slums, not just the physical one:

Residents know each other by name and reputation, and we see them call on each other for favors; the network of social ties is robust. The social capital embedded in this tight network provides a vital safety net where money is not available to do the same.

People look out for each other, and internal class distinctions are less important (this is exemplified by a landlady character who, as an area resident herself, is highly protective of her tenants and invested in their well-being).

Neighbors self-organize services to compensate for what the government does not provide; for example, in the game we encounter a makeshift orphanage and school, and a very active Neighborhood Watch group formed to ensure public safety in the absence of formal policing. (While uniformed police are seen, they work for the game’s villain, the Shinra Corporation, and it is made clear through a couple short scenes that they are uninterested in helping slum residents with their problems.)

Unslumming in the Real World

Like a real-world informal community, the slums of FF7's world offer us a snapshot in time of the process which Jane Jacobs called unslumming: incremental investment in a neighborhood by its own residents, reliant as much on exchange of skills and services and networks of local support than on (often unavailable) institutional resources such as bank loans. Here's what Jacobs says about unslumming in Boston's North End in 1961 magnum opus The Death and Life of Great American Cities:

Twenty years ago, when I first happened to see the North End, its buildings... were badly overcrowded, and the general effect was of a district taking a terrible physical beating and certainly desperately poor.

When I saw the North End again in 1959, I was amazed at the change. Dozens and dozens of buildings had been rehabilitated. Instead of mattresses against the windows there were Venetian blinds and glimpses of fresh paint.... Some of the families in the tenements had uncrowded themselves by throwing two older apartments together, and had equipped these with bathrooms, new kitchens and the like.... The streets were alive with children playing, people shopping, people strolling, people talking.

In the developing world, unslumming is fairly common and often takes the form of gradual formalization of what was once informal. This is almost always led by the residents themselves amid a backdrop of central government neglect. Rocinha, the largest and most famous favela in Rio De Janeiro, has evolved from a shanty town to a true urban neighborhood, according to Wikipedia:

Today, almost all the houses in Rocinha are made from concrete and brick. Some buildings are three and four stories tall and almost all houses have basic sanitation, plumbing and electricity. Compared to simple shanty towns or slums, Rocinha has a better developed infrastructure and hundreds of businesses such as banks, medicine stores, bus routes, cable television, including locally based channel TV ROC (TV Rocinha), and, at one time, a McDonald's franchise.[4] These factors help classify Rocinha as a favela bairro, or favela neighborhood.

Villa El Salvador in 2015. Image by Mariano Mantel via Flickr.

The pueblos jóvenes ("young towns") on Lima, Peru's barren desert outskirts have undergone a similar evolution. The 1970s settlers of Villa El Salvador set up very active community organizations from the get-go. They laid out a regular street pattern as an extension of Lima's historic grid, with room set aside for future street expansion and for public space. Today, Villa El Salvador is the terminus of Lima's first metro line.

As development spreads outward, it also becomes incrementally denser and more intense in established areas. The pueblos jóvenes have evolved from residential shantytowns into satellite cities with active commercial and industrial sectors. There is even a massive, North-American style shopping center called Mega Plaza. The distinction between the pueblos jóvenes and the city proper has in many ways functionally eroded.

Poverty persists in these places, along with problems such as access to indoor plumbing and legal land tenure. But the trajectory has been dramatically positive compared to how things started out.

Starting With Nothing and Ending Up With Something

This is, literally, the incremental development process. This is how people start with nothing and end up with something. By making repeated small improvements, anyone can build a place that generates a bit of wealth, while offering some security, stability, and the benefits of community.

This process can be interrupted, of course. But when slums fail to improve, crucially, it's almost never through some fault of the residents themselves. It's usually by a top-down disruption that stops the incremental development process in its tracks. This disruption could be the economic havoc wrought by a depression or a hyperinflation episode. Or it could more resemble the total physical destruction and dislocation of urban renewal, when U.S. cities demolished buildings and expelled residents from our last remaining places that really fit the urban "slum" characterization in the 1950s and 1960s. Jane Jacobs was a ferocious critic of urban renewal, at the time the biggest threat to the virtuous cycle she saw otherwise unfolding in places like the North End.

And in Final Fantasy 7, likewise, the biggest threat to the slum-dwellers' own improvement of their community does not come from inside—from poverty, or lack of initiative or skills—but from outside, in the form of the Shinra corporation which... well, no spoilers here. You'll have to play the game.

Many of incremental development’s values — localism, quality and civic pride — align well with those of houses of worship. If faith communities embrace this model, we could see a wave of faith-based housing that complements the broader movement toward incremental development.