Is the Coronavirus "Fuel for Urbanist Fantasies"?

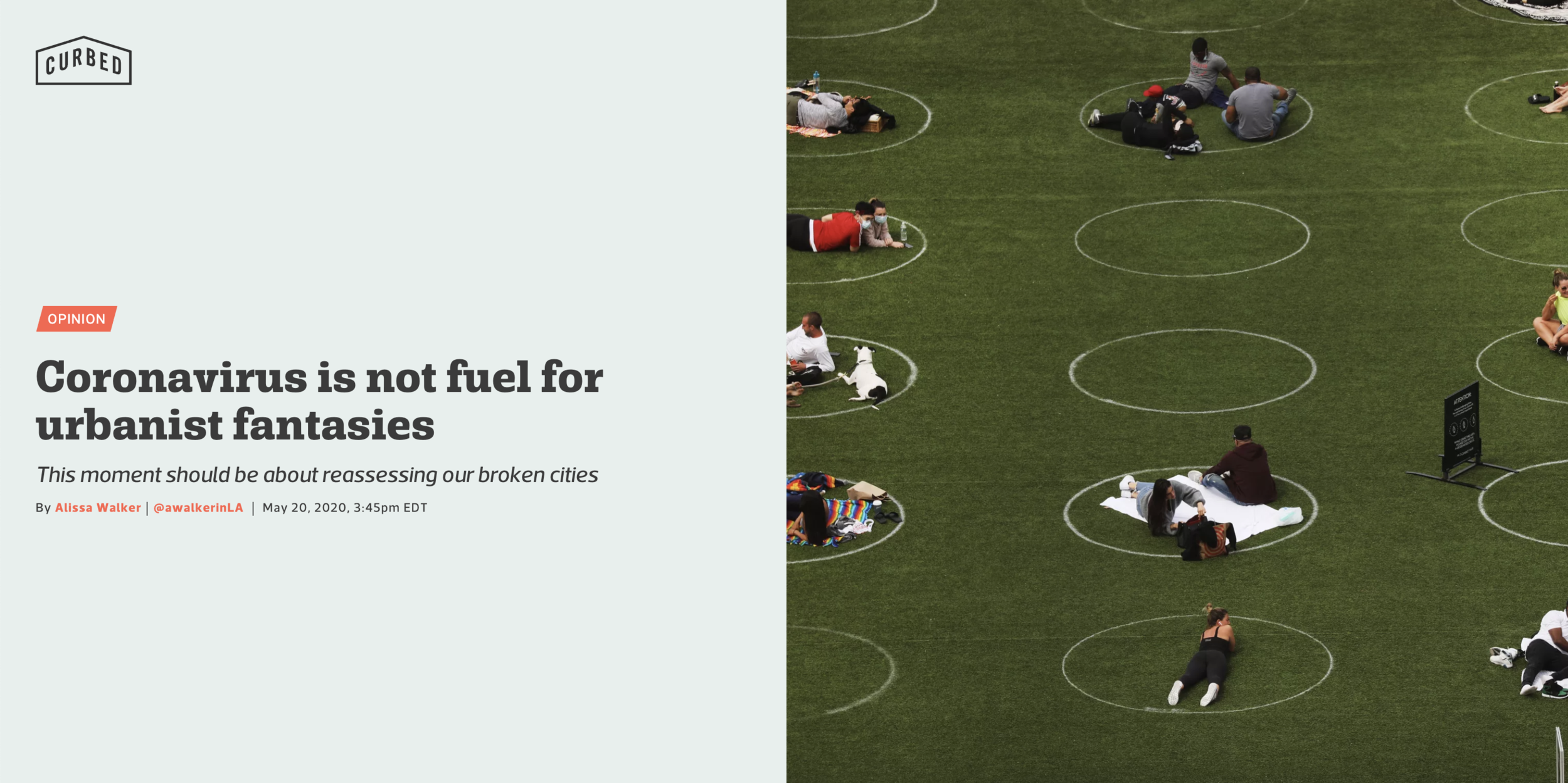

The article under discussion: “Coronavirus is not fuel for urbanist fantasies,” by Alissa Walker.

Earlier in May, Strong Towns staff read a compelling and challenging article on Curbed called “Coronavirus is not fuel for urbanist fantasies.” We decided to discuss it (in writing) and share that discussion with you all today. We began the conversation in May, but finished it this past weekend, as tensions and anger over the death of George Floyd were exploding across the country. (You’ll see more discussion of that at the end of the article.)

Please join a conversation about this article on the Strong Towns Community site to share your perspective and how this is impacting your own neighborhood.

RACHEL: This article, which came across our feeds a few weeks back, is written by Alissa Walker, a staff writer for Curbed who I’ve long been a fan of. She’s white and she’s basically calling out other white (often male) writers and thinkers in the “urbanist sphere” for jumping on the “opportunities” that the pandemic might present to advance certain issues like open streets for walking and biking, and more public space for dining. Instead, she wants to refocus attention on the disproportionately high death rates affecting people of color in America, and how these inequalities pervade so much of our cities. Our cities are “broken,” she says, and it’s time to reassess.

Daniel and Chuck, you’re two white men who sometimes operate in this sphere of talking about and offering ideas on urban issues. I’m a white woman who does the same. How do we react to this? What’s the call to action for Strong Towns advocates and what are you seeing around you in these sorts of conversations?

CHUCK: It’s a natural human tendency to view the world through your own lived experience, focusing on your own priorities. I think that is doubly true in professional realms. I joked early on in the stay-at-home order that, if aliens invaded earth, the first thing we’d do as a nation would be to lower interest rates. My point was to highlight how absurdly disconnected our urgent response is to the actual lived experiences of people.

In early February, before the pandemic really got going in North America, I wrote about how bike/walk advocates were downplaying the risk to make the case for how dangerous automobiles are. This kind of piggybacking on a separate, complex issue in order to make a point is often done with the best of intentions, but that doesn’t make it right.

Both sides of the political aisle can be guilty of reducing people’s complex struggles to talking points for a preconceived agenda. Chris Arnade (author of Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America) has pointed out how, for personal struggles, the policy response of progressives emphasizes self-improvement through education while conservatives emphasize self-improvement through increased individual responsibility. Both are projecting their own path, doing so not only without understanding but, as Chris suggests, without real respect. It’s clear we need to start with respect.

DANIEL: I’m an urban planner by training, and that’s a profession that comes in for a lot of criticism, especially from communities of color with a long history of not having a seat at the table when plans and policies that affect them are enacted. And yet I know a lot of very well-intentioned planners who chafe at hostility and criticism when they encounter it from citizens they view as the intended beneficiaries of their work. I’m talking about planners who not only genuinely value equity, but in fact, maybe the entire reason they went into the field was to make cities work better for their poorest and least advantaged residents. This is not an uncommon motivation for pursuing a local government career. (People certainly don’t do it for the money or the prestige!)

So to be told, “Stop going on about bike lanes, and focus on fixing what’s really broken about cities,” can kind of sting. It’s like, “What do you think I’m trying to do over here?!” A high-school friend of mine was killed by a truck driver while cycling. All that to say that I think a lot of “urbanist fantasies” are understood by their proponents—and I include myself in this—as one piece among many of making cities fairer and safer and better places for everyone. And a lot of the rush to institute open streets and related policies during the COVID-19 pandemic is driven by people with best intentions who are motivated by a real sense of moral urgency.

The Curbed piece, and the ongoing dialogue it’s part of (see also the work of groups like The Untokening, and advocates like Lynda Lopez and Ariel Ward) about whose voices are being heard in this rush is an important challenge to people like me, maybe even more so because of those best intentions. Walker observes, in highly specific detail, ways in which “best intentions” held by those with a particular set of life experiences lead to myopic policy that completely misses the needs of those with a very different set of life experiences. Restaurants versus street vendors. Recreational cyclists versus those who need access to the streets for very different reasons—and whose access may be conditional on things like disproportionate law enforcement.

RACHEL: I definitely felt myself getting defensive as I read Walker’s piece, but it was healthy to recognize that and ask myself why. Pete Saunders, who blogs at The Corner Side Yard recently wrote a post talking about how vastly different the experience of the pandemic has been, depending on your economic situation. For those in what he calls the “salary class” (people like us) they can basically sit out the pandemic, working from the comfort of their homes with relatively secure jobs. For those in what Saunders calls the “wage class,” the pandemic hits much harder and totally different. These are folks who have small businesses that have been devastated by the shutdown or work in the service industry, or they’re people who drive buses, deliver food, stock grocery shelves—and they’re still going to work each day under these conditions. Then finally, we have the “disenfranchised class” who were already very poor, unemployed and left behind by society—for whom things were already bad and have now gotten worse as many of the services they relied on are shut down.

I know that I am part of that salary class and Saunders says he is, too. The truth is that our work is not essential right now, but we’re getting by just fine.

I confront the fact that I am not intimately familiar with the experiences of people driving our buses or cleaning our hospital rooms right now, and so I cannot know what’s best for them. That’s where Walker’s indictment is prescient. It’s natural for folks like me who miss eating at restaurants to think about how we could get back to doing that safely—and I have a lot of friends in the service industry so I think about how they could get back to work, too...

But Walker is right: what’s far more important right now is figuring out how everyone in our neighborhoods can be safe and healthy. For me, the most important work is pushing past barriers that divide us by class and race, and getting to know my neighbors more fully.

Daniel and Chuck, where do you think the Strong Towns message fits into all of this?

Read more at “The Strong Towns Approach to Public Investment.”

CHUCK: We’ve definitely seen who the essential workers are. They aren’t the ones who are comfortable right now. They also aren’t the ones we are showering resources upon. In other words: they aren’t the ones the current system is set up to respond to.

Getting to know our neighbors is an essential step for building a successful place, but since most Americans live in enclaves separated by class (and, as an extension, often by race), it’s not a strategy that I think will move us substantively past division. For that, we need to shift power through bottom-up systems that are responsive to the urgent needs of people, not merely guardians of the status quo.

I don’t pretend that a Strong Towns approach can heal all class divides any more than I’ll claim it cures cancer, but moving beyond listening (from a position of comfort) to actually taking some action is central to what we’re about. Equally important is that those actions be based on a humble observation of real struggles, literally experiencing the city as the people we are serving experience it.

Instead of being responsive to top-down systems, we orient ourselves to become responsive to people, especially those who are struggling. So many of the people I have seen fall victim to the dual health/economic challenge of COVID-19 are people who had no alternative but to put themselves at risk. They live isolated in places not designed for their needs. The Strong Towns movement can’t fix all of that, but we all have the capacity to make things a lot better together.

DANIEL: The challenge for me is how you implement that bottom-up responsiveness.

Ruben Anderson wrote an excellent piece about how public engagement-as-usual is worse than worthless: it actually erodes trust, because it is set up to fail to be meaningful or actionable. We ask members of the public to weigh in on things they’re not experts on (“How wide should these travel lanes be?”), we don’t ask them to weigh in on the things they are experts on (“Where do you feel unsafe while navigating your neighborhood?”), and then we ignore their non-expert input where it clashes with expert best practices, leaving most people feeling used, while the conversation ends up dominated by the loudest voices in the room.

Starting with needs and struggles has to look different than the status quo. Rachel, you’re the one among the three of us who isn’t trained as an urban planner, so I’m curious from your perspective what you would like to see planning look like. What would it look like for planners to truly act as public servants—to start with respect and humble observation and not as salespeople for “urbanist fantasies” we believe are the right thing to do?

RACHEL: The three of us began writing this discussion earlier in May and a lot has happened since then—catalyzed by the murder of George Floyd. All of us grew up in Minnesota, and Daniel and I were raised in St. Paul and Minneapolis, respectively, so the explosion of anger over racism and police brutality there has hit home particularly hard as we hear from family and friends about what things look like on the ground.

For Strong Towns advocates, our message isn’t the sort of thing that intervenes instantaneously during crises like these. (And that’s not typically the work of planners either.) Rather, we participate in an incremental process that builds up neighborhoods over time so that they can become resilient places where it’s possible to live good, healthy, successful lives. In addition to building up local prosperity, I believe that process should also involve an examination of the role of law enforcement and broader issues of structural equity, so that we ensure economic prosperity is accessible to all residents. Our neighborhood groups, religious communities, schools and other local spaces should be the source of this change—with government leaders, planners, and others in power constantly humbling themselves to listen to their residents’ voices, and not waiting for moments of horror to be a wake-up call.

We know that these changes don’t happen overnight, but they are why I come to work every day.

CHUCK: Sometimes structural changes do happen overnight, though not peacefully and not without deep damage. We started this conversation responding to a call-out for us—specifically white, male, urban planners—to stop with the fetishization of cities as amenities for the affluent and start addressing how they are deeply broken for many of the people who live there. I couldn't agree more with that critique. It’s hard to deny the urgency of that call.

Please join us on the Strong Towns Community site if you’d like to discuss these issues further. We welcome your perspective.

Cover image via Gustavo Fring.

Upcoming Free Webcast

Open for Whom?

Streets as a Platform for Recovery

Tuesday, June 16

12 p.m. CDT

Crisis precipitates change. The novel Coronavirus has transformed our lived experience in the blink of an eye, generating mass uncertainty and economic upheaval while laying bare the inequities of America’s culture of white supremacy. As we witness the struggle to maintain a sense of self, purpose, and hope, it is paramount to understand that the collective utility of the street has never before played such a crucial role in determining our American destiny.

In this free webinar, Tamika Butler, Esq and Jason DeGray P.E., PTOE of Toole Design will discuss equitable, ethical, and empathetic approaches to “open streets” recovery initiatives.

This presentation will:

Table pre-pandemic agendas

Reflect on the nuance of how people rely on streets

Address the need to dismantle racial, economic, and environmental inequities for streets to be truly open

Identify the need for those who are most impacted by changes to the street to have the most power to shape those changes

Provide practical considerations for deploying open streets

During a recent Planning Commission meeting in Windsor, California, Vice Chair Tim Zahner advocated for using the Strong Towns approach to make the city's streets safer.