Asphalt City: How Parking Ate an American Metropolis

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a long-term series exploring the history of Kansas City and the financial ramifications of its development pattern. It is based on a detailed survey of fiscal geography—its sources of tax revenue and its major expenses, its street network and its historical development patterns—conducted by geoanalytics firm Urban3. Here are all the articles in the series:

Kansas City's Fateful Suburban Experiment • Is Kansas City Still Living on Its Streetcar-Era Inheritance? • "Kansas City's Blitz": How Freeway-Building Blew Up Urban Wealth • The Road to Insolvency is Long • Asphalt City: How Parking Ate an American Metropolis •

The Local Case for Reparations • Ready, Fire Aim: Tax Incentives in Kansas City (Part 1) •

The Opportunity Cost of Tax Incentives in Kansas City (Part 2) • The Numbers Don’t Lie •

Kansas City Has Everything It Needs

In previous installments in this series, we've described how Kansas City, Missouri and its metropolitan region went from a showpiece for streetcars and City Beautiful planning to an automotive metropolis. After World War II, Kansas City built freeways with zeal, demolishing neighborhoods and carving up the city's core in swaths of destruction so total that residents compared it to the London Blitz. At the same time, an annexation frenzy by city leaders determined to keep up with the forces of suburbanization (instead of outright losing residents to the suburbs, as their peer city of St. Louis was at the time) just helped supercharge those forces. Annexation and outward expansion saddled Kansas City with a 169% increase in its road obligations, even as the population living within the city’s prewar borders fell by roughly half.

We still, however, haven't tackled one of the biggest transformations that Kansas City's total embrace of the automotive, commuter culture wrought upon the city's historic fabric. And that is parking.

Parking is the dominant physical feature of postwar North American cities. It dictates their form more than anything else does. The perceived, actual, or legally mandated need for parking determines where a building can sit on a lot, how big it can be, and how it relates (or doesn’t) to the street, sidewalk, and adjoining properties. Parking makes many beloved kinds of places all but impossible to build or sustain. We all kneel at the altar of King Parking.

And yet we often don't see parking. It's such a mundane, ubiquitous filler between the places we actually want to be that it’s hard to visually register just how much space is consumed by private car storage, and what an albatross it is around our necks in terms of resources.

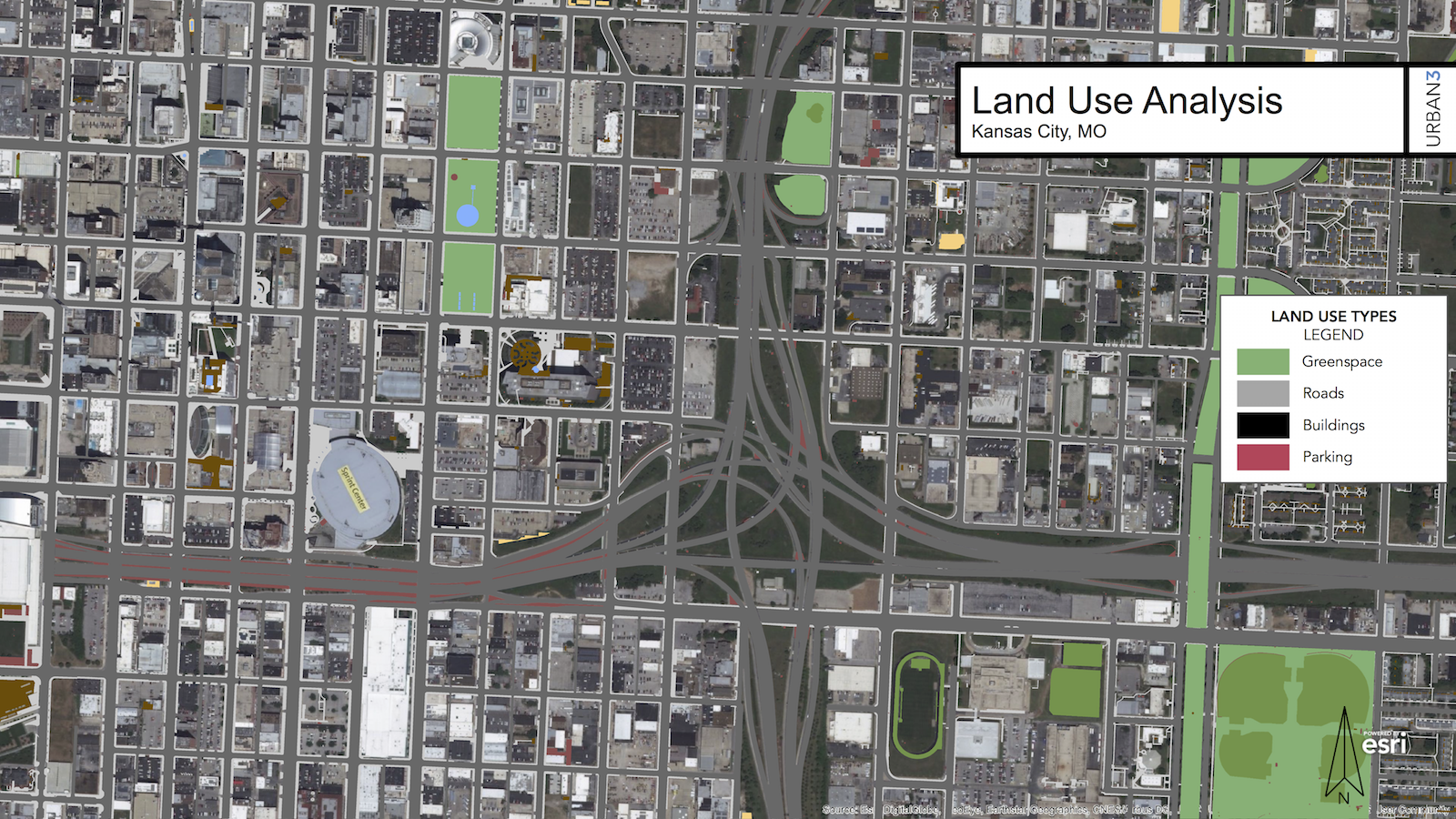

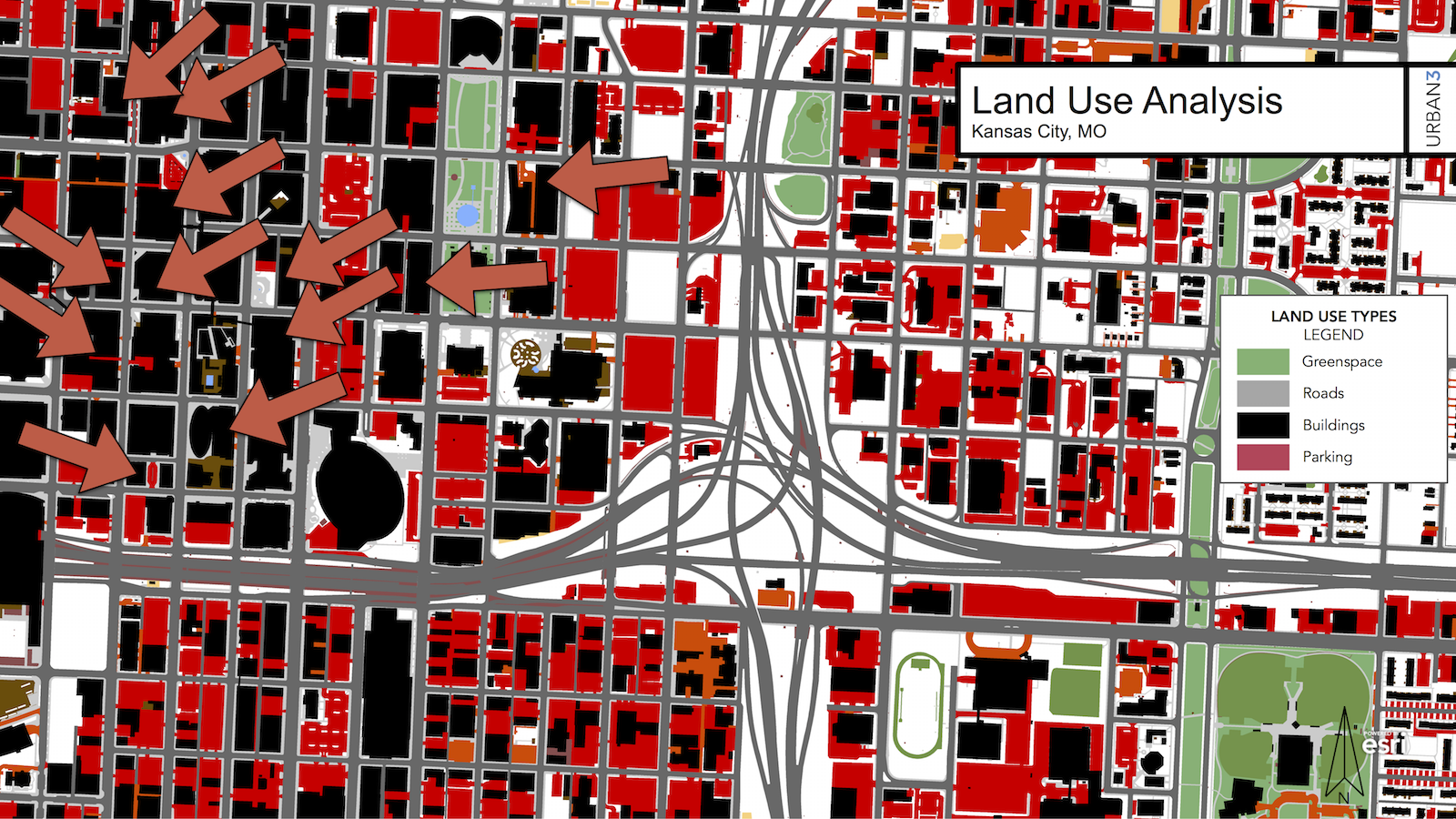

Urban3's fiscal geography of Kansas City includes a detailed breakdown of the entire city’s uses of land. Let’s zoom in on downtown first. As you advance through the below slide show, you can watch green space populate, then roads and buildings, and finally see parking (in red) eat up downtown KC in dramatic fashion:

The arrows in the final slide point to enclosed parking structures—not all of these consist entirely of parking, but all have at least some parking.

Part of the reason there's so much surface parking downtown specifically has less to do with commuter needs, and more to do with the temporary hollowing out of demand for downtown real estate as the suburbs boomed in the late 20th century. If you wanted to speculate on some downtown Kansas City land by buying it when it was cheap and waiting—even for decades—to sell to a developer, slapping a parking lot on that land was an easy way to make a bit of income in the interim. This pattern exists across North America: many of these lots are privately owned and, while they may bring in more than enough revenue to pay the low property taxes on unimproved asphalt, the point isn't really the parking operation. The point is land speculation.

Kansas City’s downtown is particularly distinguished by its glut of parking lots—enough that it has been a repeat contestant in Streetsblog’s annual parking crater contest. But the rest of the city has not been spared the ravages of the hungry beast. Here's parking citywide (in red):

It’s hard to tell how much red there is in the above map, other than “a lot.” But we can quantify it: the Urban3 team categorized all of Kansas City’s land cover into streets, buildings, parking (taxable and non-taxable), and other uses. The "other" is a grab bag that includes many things, from private driveways, to yards and other green space (including undeveloped land, which is still plentiful in some of the city’s annexed northern reaches), to parks and athletic fields to freeway medians to water. Here’s the breakdown—and on the right, you can see both the total and per-acre value of each category.

Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of the city’s taxable property value is coming from its buildings, where productive activity takes place. (It’s worth noting that the “value” of parking in this case is based on the cost of the raw asphalt, because that’s how the city assesses land improvements. It’s not based on the value proposition of the access that parking provides.)

Note that the roads impose a net cost: you can think of this as their life-cycle replacement cost. It is not to say that the city should not have any (of course, it could not function without streets), but rather that a street requires perpetual maintenance and should be treated by cities as accounting liabilities, not assets.

Another way to visualize the above data is per capita. Here's how much land is devoted to buildings, parking (taxable and non-taxable), and roads, for each Kansas City resident:

The scale illustration, complete with human figure, helps convey the extent of Asphalt City: that's 1219 square feet of parking just for you. The same for your mother, father, spouse, roommate, child, etc.

What could you do with 1219 square feet? How many people live in homes smaller than that? This is not all residential parking: this includes parking spaces at stores and restaurants, at offices, at schools, at stadiums and parks, at places of worship; all in all, far more than will ever be occupied at any one time.

Separation of land uses—a hallmark of the Suburban Experiment, and of much of Kansas City developed post-1940s—requires a huge amount of redundancy, because the spread-out and car-centric development pattern renders it difficult to make trips on foot, or to park once and then visit multiple destinations. When offices (daytime) and restaurants (nighttime) aren't in the same neighborhood, or homes (nighttime) and retail (daytime) aren’t interspersed, they can't double up on their use of shared street parking the way they would in a mixed-use environment.

More than twice as much land in Kansas City is devoted to asphalt as to buildings. For each resident there are 1,065 square feet of building and 2,347 square feet of streets and parking. In total, it all adds up to 18.8 square miles of buildings and 41.4 square miles of asphalt (the slight discrepancy in the ratio is because the citywide figure includes estimates of things such as private driveways). Kansas City isn't that unusual here: you'll find a similar ratio in almost any suburb and many other big cities. Once we remove yards and various buffers, we devote significantly more of our developed land to cars than to people who aren’t in cars. And we’re learning that it doesn’t work out financially.

But we don't see it until we really look at the data.

Cover image via Wikimedia Commons.

How Much Is Excess Parking Costing YOUR City?

Parking minimums are probably costing your town or city a lot of money—not only in actual dollars, but in huge opportunity costs. The good news: we can turn this around.

In this free ebook, you will find out why the U.S. has so much excess parking (some estimates have it comparable to the combined size of Delaware and Rhode Island), why it’s costing your town money, and the simple fix cities around North America are using to stop squandering their resources and start building great places again.

Parking minimums are hurting American cities. Let’s unleash our towns and cities so they can start building real, lasting prosperity again.

Daniel Herriges has been a regular contributor to Strong Towns since 2015 and is a founding member of the Strong Towns movement. He is the co-author of Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis, with Charles Marohn. Daniel now works as the Policy Director at the Parking Reform Network, an organization which seeks to accelerate the reform of harmful parking policies by educating the public about these policies and serving as a connecting hub for advocates and policy makers. Daniel’s work reflects a lifelong fascination with cities and how they work. When he’s not perusing maps (for work or pleasure), he can be found exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods on foot or bicycle. Daniel has lived in Northern California and Southwest Florida, and he now resides back in his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, along with his wife and two children. Daniel has a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota.