6 Things to Know About How Development Works

Photo by Aditya Chinchure on Unsplash

Depending on the circles you travel in, the word "developer" may elicit a strong reaction in you. Maybe you hate and mistrust them; maybe you see them as enterprising risk-takers improving your community; maybe you are one. (If you are one, this article is probably not for you.) Americans have strong opinions about real-estate developers as professions go, to the point where academic research has even found that one of the strongest predictors of how opposed people will be to a new building in their neighborhood is whether they think a developer is going to make a profit from it.

There is, however, a lot of misunderstanding about what developers do and how their business model works. Here's a super-dumbed-down, 101 guide to six things you want to understand if you're going to have informed conversations about development in your community. (This article will focus on housing, but note that some of these apply more broadly to retail, office buildings, or any sort of project.)

1. "Developer" is a broader category than you think.

Who builds new homes in your community?

Who built the oldest homes in your community?

Who built the home you live in?

The answer to all of these is: a developer. By definition, development is just any activity that increases the market value of a piece of real estate by building something on it. There's a certain irony when community activists decry "developers" as profiteering interlopers whose motives stand in opposition to the purer, gentler interests of existing neighborhood residents—since those neighborhoods must have at some point been the latest new development themselves. (Daniel Kay Hertz memorably calls this the "immaculate conception theory of your neighborhood's origins.")

But it is true that the category of developer used to look a lot different than it does today. In "The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of the Triple Decker," the New England Historical Society explores that region's iconic triplex houses. All over Massachusetts and Rhode Island in particular, starting in the late 19th century, triple-deckers were erected by many hundreds of manufacturers, "mill owners, small builders and carpenters." The ante required to be a developer of a single home on a single lot, or a small cluster of homes, was simply not that great, and with vernacular architecture and passed-down building techniques, it didn't have to be your primary career.

The "developers" of the day—if they even used the term—were a far cry from the industrial-scale homebuilders of today like Lennar or Del Webb. The Suburban Experiment, with the rise of whole neighborhoods built to a finished state, has changed the face of development and what we expect a "developer" to be.

2. The cost of building sets the floor under the price of a brand new home—and it's not cheap.

The most common misguided refrain I hear in debates about housing affordability is the following:

The problem is that these developers aren't building any affordable homes, only luxury. They need to build homes that working-class people can afford.

Imagine if we asked the same thing of Ford or Toyota. "You have to sell a brand new Escape for $5,000, because that's the most many of our working-class customers can afford." Of course, Ford won't do that, because the Escape costs more than that to make.

We don't as often apply this logic to housing, I suspect, because many people have very little sense of the actual cost of building a house. We know there are cheaper houses in our communities, so we assume new houses could be that cheap if the developer were willing to forgo a bit of profit. In reality, the "used" house is much like a used car—it can be much cheaper than the cost of creating it in the first place, because it's already there and it is merely changing ownership. The theoretical floor on the price of a “used” home is zero.

A new house, however, will never be cheaper than the cost of creating it. Not without some sort of subsidy, since nobody's going to build at a loss.

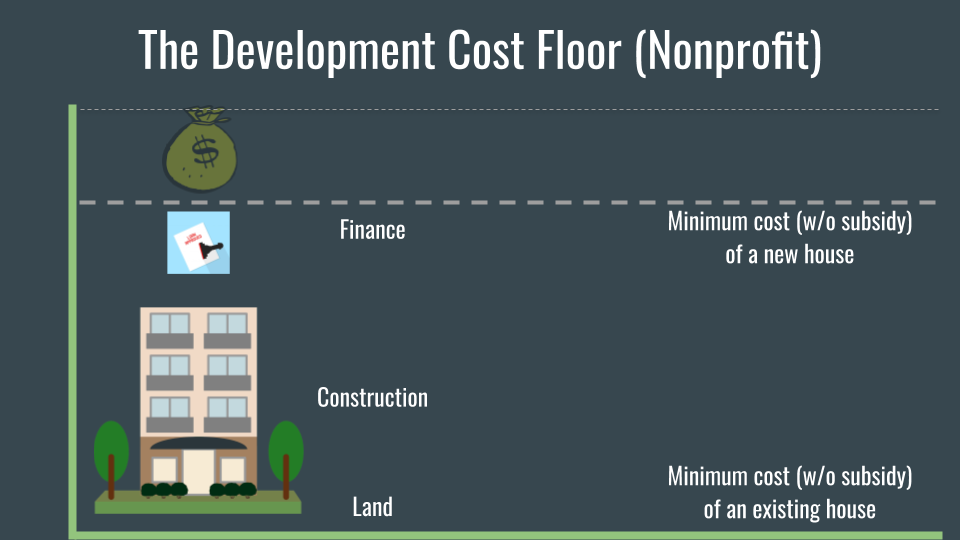

3. Even nonprofit developers have a "floor" unless subsidies are involved.

The exact same "floor" logic applies to nonprofit developers, like those that build dedicated affordable housing. A nonprofit may not expect a return on their investment at the end of the day, but they still have to be in the black. If they spend more money than they bring back in, they won't be able to keep building homes for very long.

These are 2017 estimates, courtesy of the Government Accountability Office, of the median per-unit cost of building subsidized homes for low-income residents in various markets across the U.S. This is the actual cost to build, not the price to the eventual inhabitant.

Here is a 2019 exercise by the Terner Center at UC Berkeley in modeling the construction cost—which, again, is the bare minimum sale price if no subsidy is involved—of affordable housing in Northern California, for many reasons one of the costliest places to build:

4. The rent on new apartments pays the cost of building them.

Here's the development business model in a nutshell. On the left are the expenses associated with building:

Buy the land

Pay for the architect, legal fees, permitting fees, marketing, etc. ("Soft Costs")

Pay for the actual construction, landscaping, electrical, plumbing, HVAC, etc. ("Hard Costs")

Pay interest on your construction loan

On the right are the two main sources of financing for development: equity (that is, cash the developer or any investor partners put forth) and debt—that is, a loan.

If you're building rental homes, the way you pay off this loan is through the rents you bring in after the building is occupied. There's nuance I'm leaving out—often some fancy refinancing is involved, for example. But the bottom line is that the rents on a new apartment building are how its construction is paid for. And this sets a floor under them, much like there's a floor under the sale price of new for-sale housing.

The rent coming in must cover the following things:

The cost of operating the building

Capital reserves for bigger maintenance needs, like an eventual roof or HVAC repair

Debt service, i.e. paying off the construction loan

A debt coverage ratio, or a buffer in case of vacancy or higher-than-anticipated expenses. The bank demands to see this ratio before they authorize a construction loan, so they know the borrower won't be likely to default.

So again, the problem with saying, "Nobody can afford the rents on these swanky new apartments; they need to set the rent lower!" is that it doesn't ask whether the developer can actually afford to set the rent much lower than it is. Perhaps surprisingly, the answer—for brand new construction—is often no.

Again, older, existing buildings—even just a little bit older—are an entirely different ballgame. Because they already exist, the cost, like that of a used car, depends only on what a buyer is willing to pay and what a seller is willing to accept.

5. The price of land depends heavily on its development potential.

Stop me if you've heard this one before:

Housing is expensive in cities because the land is so expensive. Dense development is more affordable because it splits that land cost many ways.

This isn't completely false. But it's a simplification. Here's why:

Imagine you own a vacant lot, and you are approached by two developers. One wants to build a single-family home like the one pictured on the left below. The other wants to build an apartment building like the one pictured on the right.

Which developer do you think can afford to pay you more for the lot? Whose offer are you going to accept?

This thought experiment demonstrates that the price of land is affected heavily by its development potential, because that affects what a buyer can afford to bid. If you upzone land to allow more density, you've just made it more potentially profitable. And the price will rise accordingly. (But, it's important to say, usually less than proportionately. And so it's still true that density tends to mean lower land costs per housing unit, just not lower overall.)

6. Developers don't tend to make huge windfall profits. Land owners do.

There's one more important corollary of the point about land costs above.

Suppose Developer X and Developer Y both have their eye on the same vacant lot. X has a project in mind that will deliver an 8% rate of return (think: profit margin) if she can get the land for $100,000. Y is greedy and wants a 20% rate of return—but to make this kind of profit on his project, he needs to pay no more than $40,000 for the land.

Who is the land owner going to sell to? Clearly X, not Y.

In general, in a strong market, a patient seller of land (or a redevelopment site, like a gas station that can be torn down) can hold out for the highest bidder, and not accept a lowball offer. This means that the land owner can bid up the price to just about as high as it will go while still leaving some sort of construction viable.

To reiterate: it is very difficult in a competitive market for a developer to reap a windfall profit, because another developer who's willing to settle for less profit can just outbid them for the same plot of land.

Who actually pockets a huge profit in this transaction? The land owner who sells to the developer.

This is important to understand when asking who benefits from high land (and thus housing) prices in cities. It's a myth that it's predominantly the "greedy developer" who does. The most reliable beneficiaries of high prices are land owners: specifically, those who bought property cheap years ago and have been sitting on it for a long time. (And this includes homeowners who sell to other homeowners, not to a developer at all. Homeowners are in fact, numerically, the biggest land speculators in cities and often the primary beneficiaries of a growing economy that drives rising land values.)

This article isn’t meant to paint developers as either virtuous or villainous. The reality is, they’re business people, and if you want to influence what they do, it helps to understand how their business model works.

As Norwalk navigates a housing crisis, one thing is clear: the path forward isn’t scale for scale’s sake—it’s building smarter, more affordably, and with the community in mind.