Low-Income Families in Philly Want to Build Their Own Future

Philadelphia, PA. Image by Edan Cohen on Unsplash

In the city of Philadelphia, a group of families have stepped in where the government is failing them. They’re fixing up old, vacant buildings on their own dime while a government agency pursues expensive, new construction. These families dream of taking ownership of the buildings they’ve worked on, so that they become safe, economically productive investments.

As Shelterforce reports in a recent article:

Eeg Stremist [a pseudonym] and her family are among about 50 people who have taken over 12 vacant [Philadelphia Housing Authority] properties since late March, according to Jennifer Bennetch, an Occupy PHA activist who led the home takeovers. Most are single moms and their kids. They’ve spackled walls, patched roofs, fixed leaky plumbing, and registered utilities in their own names, while waiting to see if the PHA will send its private police force to evict them from the homes. PHA says it knows of about 20 homes with squatters.

Set aside however you might feel about public housing and hear this as a story about low-income neighbors who want to live in a home, just like everyone else. They see available properties being neglected and they take the initiative to fix them up themselves. These families want independence and ownership—goals that many American share.

Some of these families were likely living in their cars, crashing temporarily with friends or patching together stays at homeless shelters. Now, at least for the moment, they have some autonomy and control over their living situation. Stremist, for instance, mentions that her older children (she’s a mother of nine) had had to live separately from her until they moved into the PHA property. We don’t know the details of why, but, given my own experience working at homeless shelters, I can almost guarantee that it was because precarious, temporary sleeping situations like shelters nearly always come with restrictions on who can stay and how many people are welcome.

Why are hundreds of homes owned by the Philadelphia Housing Authority sitting vacant when families need places to live? The Shelterforce article quotes local housing advocate Jennifer Bennetch with her explanation:

“PHA isn’t keeping up. They’re not coming in and renovating the properties and moving people in. They just board them up and never come back to them. So the number just grows. By the time they come back to them, they’ve become dilapidated. Water is coming in the roof and there’s water in the basement,” Jennifer Bennetch [a homeowner and housing activist in North Philadelphia] says.

The way the PHA treats its properties is, unfortunately, not unlike the way many government entities treat their infrastructure. When budgeting for projects today, local governments rarely plan for the long-term maintenance costs these projects will incur over their lifetime. Then, as a bridge or pipe or home falls into disrepair, the government looks for new projects they can pursue using new pots of money or outside revenue sources. The mayor or city council gets to point to a shiny, new thing they built, while the old, dilapidated thing gets further neglected.

Why do we do this? Why do we keep building and building when we can’t even maintain the stuff we already have? In the case of the PHA and other housing organizations, it might be because money for new projects—from state and federal government sources—is easier to come by than money for basic updates. From the Shelterforce article:

Rather than putting that money toward basic upgrades at aging, dilapidated structures, the agency regularly sells properties to raise cash for new construction, [PHA CEO Kelvin Jeremiah] says. The goal is to build modern homes that are well-integrated into neighborhoods, replacing the isolated superblocks of high-rise towers that PHA put up in the mid-20th century.

It’s a worthy goal; if you’ve spent any time living in or learning about old public housing buildings, you know that most are rough places to be. But this model of aiming to build new when you can’t even manage to make basic fixes on what you have sounds a bit like putting a fancy sports car on a credit card when you can’t even afford an oil change for your ten-year-old Honda Civic—and all while your children need rides to get to school. I yearn for a world where everyone can live in high-quality housing, but having sufficient housing for everyone should be the first goal, rather than giving a few people nice new homes while the rest must sleep in their cars, in shelters or on the street. And we haven’t even started talking about what happens when those new homes eventually need fixing up in a couple decades…

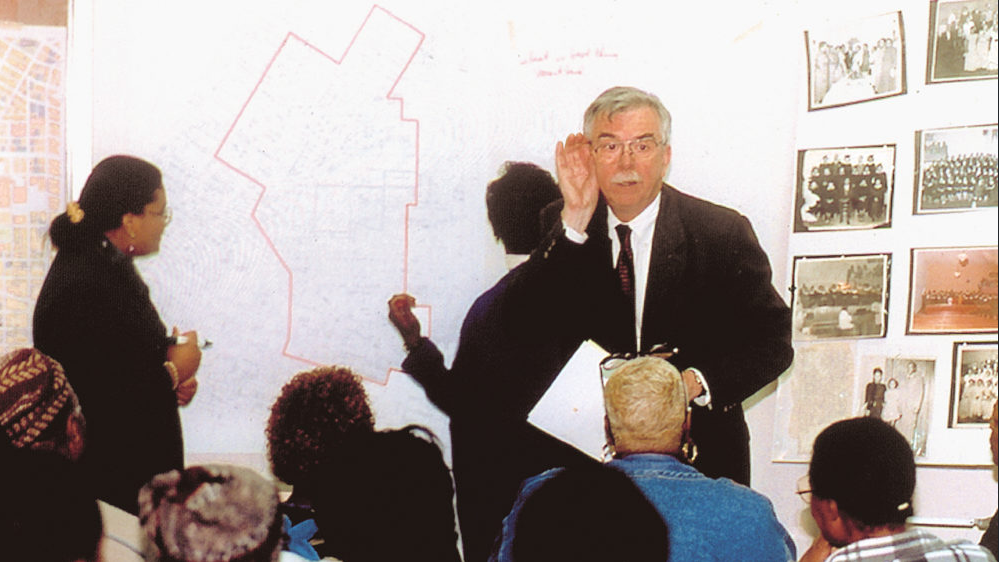

The design for the Philadelphia Housing Authority’s new headquarters in North Philadelphia. Image source.

Advocates in Philadelphia are pushing for maintenance over new construction in the hopes of getting more housing for people who need it. From Shelterforce:

PHA’s critics say it should spend more of its $470 million budget on maintenance and rehabilitation and less on non-housing expenses like its 30-member private police force and Jeremiah’s annual salary of $350,000. They also criticize the agency’s new $45 million headquarters, which opened last year as part of a half-billion dollar mixed-use redevelopment in North Philadelphia’s Sharswood neighborhood. […]

Protest organizers also fault the housing authority for what they call a privatization strategy, in which it sells off properties to raise funds for construction and capital improvement, and partners with private developers to rehabilitate old units. […]

Residents are tired of watching the PHA focus on building expensive new construction. They want to take matters into their own hands, using the homes that already exist, fixing them up and, ideally, taking over their ownership so they can determine their own futures. Here’s a final quote from the article:

Bennetch and others say that instead of selling properties to afford pricey new ones, the authority should do relatively inexpensive renovations of existing units or give properties away to residents.

The coalition activists say they want to create a new community land trust that would manage the acquired homes cheaply without government support. It would depend on the contributions and labor of residents and community members, much as Stremist and the other squatters are doing now.

This is a story of neighbors whose voices aren’t often heard, stepping up and doing what needs to be done to keep their families safe and provide for their basic needs. If we want to build financially strong towns where all residents can live good, prosperous lives, we must pay attention to the people who are showing us what they need and demonstrating a clear path to achieve that with the limited resources at hand.

The Christmas Cookie Inflation Index has risen 6.2% in the last year. This is compared to the official inflation rate of 2.6%.