All In Good Time

Strong Towns member Johnny Sanphillippo blogs at Granola Shotgun. This post is republished from his blog with permission.

Image via Google

I recently received an email from a graduate student in Halifax, Nova Scotia asking about a project he’s been tasked with designing. The hypothetical redevelopment site is a collection of retail, commercial, and light industrial properties that are mostly still commercially viable, but isolated, disconnected, single-use, and underwhelming from a municipal, societal, and environmental perspective. Here’s a portion of the brief he was given:

Is there an opportunity to redevelop retail parks to accommodate the Municipality’s future growth without contributing to additional sprawl? Is there a realistic prospect of redeveloping these retail parks as complete communities? What land use strategies should be considered? How could transportation challenges be addressed? How can land use conflicts with nearby industrial uses be considered and/or mitigated?

I’m going to start by break down my reply about Halifax into a few chunks. First, this is a completely normative North American landscape. Throw a dart at a map randomly anywhere between Ciudad Juárez and Nunavut and there’s a good chance it will land on a place very much like this. Second, the options available to what can and can’t be done with the territory are determined by rigid institutional parameters with very little wiggle room for deviation. Third, the cost of compliance for a standardized redevelopment approach is pretty high, but the cost of anything avant-garde will be even higher. There’s a limit to what people are willing to pay for in suburban Halifax. Finally, I say embrace the suburban status quo—but do so with an eye toward how these places may evolve over time toward a future shaped by different forces.

Image via Google.

I mapped out a path from the Costco parking lot in the north to the Tim Hortons drive thru to the south to see what scale we’re talking about. That’s a three-kilometer, 35-minute walk past the Burger King, Marshall’s, Dollarama, Petro-Canada & Car Wash, and the Nothin’ Fancy Furniture Warehouse. Of course, no one would ever walk that route unless they were indigent and desperate. A municipal bus exists here and connects the neighborhood to the rest of Halifax, but I have no doubt it’s a slow and miserable experience. It always is in these kinds of places. I wouldn’t spend too much time or effort trying to upgrade public transit under the circumstances. We need to be honest about what this place is and what it isn’t.

Images via Google.

Just for giggles, here’s a three-kilometer, 35-minute walk in Florence from the Ponte alla Vittoria to the Torre della Zecca along the Arno. This path twists casually by the Piazza Carlo Goldoni, the Piazza della Santa Croce, and the Palazzo Vecchio. In defense of Bayer’s Lake in Halifax, Florence did have a 2,000 year head start. Florence had modest beginnings too. In 59 BC Julius Cesar established it as a settlement for veteran soldiers and it was no doubt a cookie cutter town back then. Those soldiers and their wives might have enjoyed a trip to the HomeSense and Dairy Queen after long campaigns subduing Gaul and Egypt. The Florence we know today emerged incrementally over centuries and in ways the first inhabitants probably couldn’t have imagined and might not have approved of. These things take time.

Images via Google.

Does anyone believe the PetSmart will still be around in a hundred years? Let me put a finer point on this. Whatever replaces the PetSmart after the building is scraped probably won’t survive for a century. These structures are designed using amortization and depreciation tables to last just long enough to cover the loan period, spin off some cash flow, and enjoy tax deductions. After that, they’re essentially toast. The franchise shops that occupy these buildings are themselves ephemeral. Remember Blockbuster Video and Borders Books? Will the Halifax Chrysler Dodge dealership endure? Everything has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Bayer’s Lake in its current incarnation is disposable by design.

Image via Google.

Image via Google.

So there are two paths to plan for. The site either returns to nature after a period of disinvestment and depopulation, or it’s repeatedly reinvented and improved until it achieves the Florence status long after we’re all dead. Either way it’s all about baby steps—up or down. I recommend relaxing about “sprawl.” The best suburbs will endure in a different more substantial form. The worst won’t be around for very much longer in the big scheme of things. The Earth won’t even notice they were there. Neither will civilization.

I found an article from The Coast from November of 2017 that depicts the proposed development of a nearby tract. Someone broke out the colored pencils and filled in the little blocks on the zoning map. Single family homes in yellow, semi-detached homes in lavender, townhouse condos in powder blue, and apartment blocks in orange. In between are green patches labeled “parks,” but they’re really storm water retention ponds and mandatory lake setbacks. This is what many people think of as a “complete community” because it has a variety of housing types at different price points. People can migrate from a rented apartment, to a starter condo, to a house with a yard, and then to a retirement condo. It’s all right there in candy colors.

Image via Google.

The idea that a neighborhood might need other things in addition to housing, parking, greenery, and maybe a school tends not to fly. Why would anyone want to live next door to shops or offices? Do we even need shops or offices anymore when everything can be pushed through a fiber optic line or be delivered in a panel van? It’s better to keep undesirables and traffic away from private homes. Think of the children!

This site, like all development sites, is subject to a lengthy review process where the locals come out and object. Sometimes it’s rich white people with the pitchforks and firebrands. Sometimes it’s poor black people. It might be Hasidic Jews or First Nations or a riled up group of Mormons or lesbian environmentalists. It doesn’t matter. They’re extras from Central Casting. The public review process at City Hall has a slot in the schedule waiting for them. The developer has already engaged the services of a consulting firm to smooth over everyone’s feathers. The procedures grind on as predictably as the final results. It’s all a cost of doing business that’s baked into the price of the completed project.

Notice how each of these tracts are intentionally disconnected from everything around them. If planners proposed connecting developments to each other with so much as a bicycle path there might be stiff resistance. The self-selecting demographic that chooses to live in these subdivisions doesn’t always want strangers wandering past their front garden at all hours. Mostly what is desired is a thick stand of pine trees and a fence to buffer them from the outside world. The path, if it must exist, should be circular and meant for residents only. Walking and biking is for leisure and exercise, not a form of transportation. And how would anyone walk or bike home from Costco with industrial size groceries anyway?

Image via Google.

Image via Google.

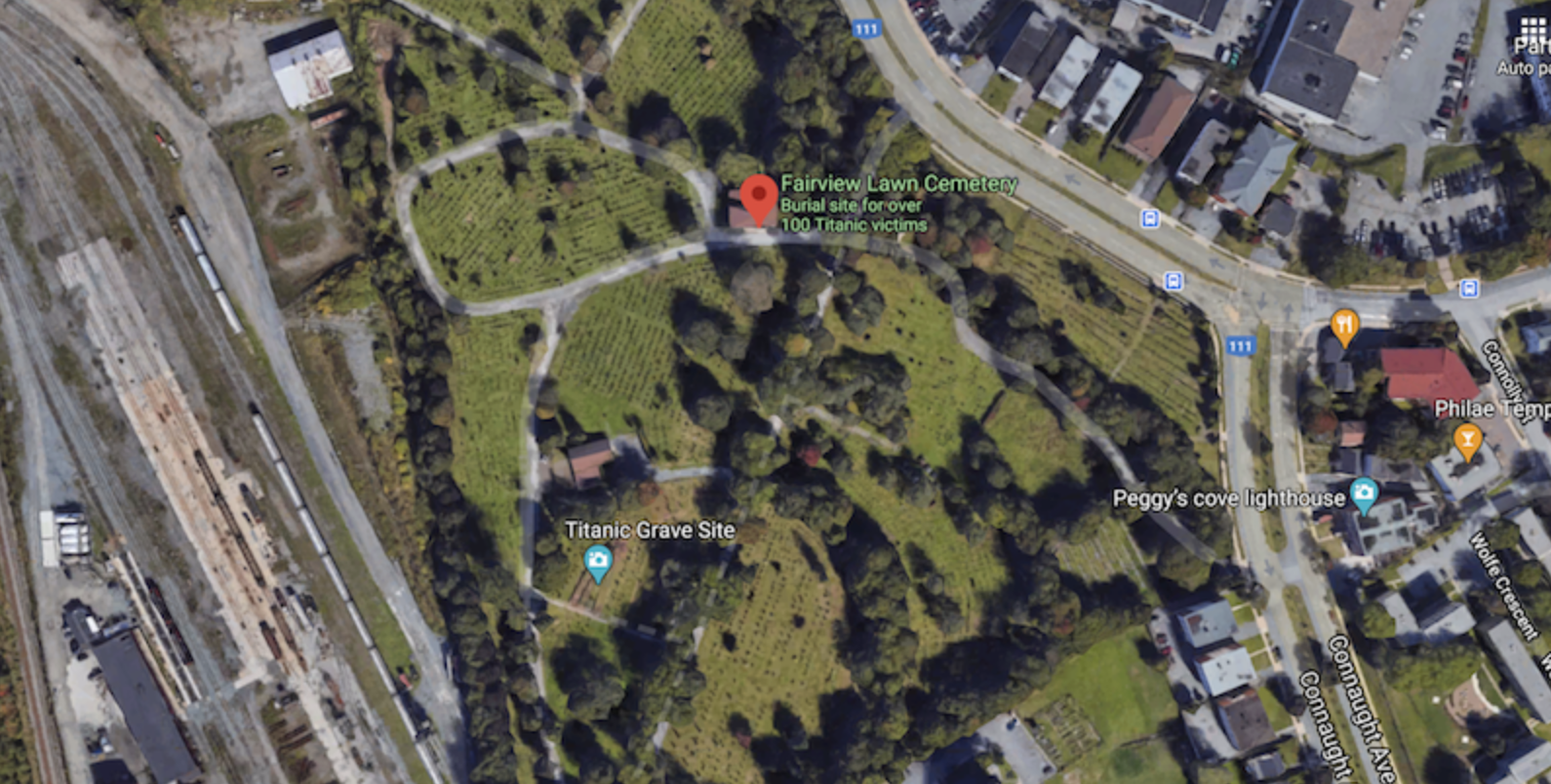

The swirly curvilinear streets of the typical suburban subdivision are based on the cemeteries of the late 1800s. Halifax’s Fairview Lawn, final resting place of victims of the Titanic, demonstrates the precursor of every modern cul-de-sac housing development. Streets twist through a parklike landscape of grass and trees insulated from the outside world. It’s peaceful. And it’s a complete break from both military gridiron urban blocks and the chaotic tangle of streets of ancient towns.

I’ve seen a trend in new suburban homes nearly everywhere in recent years. They’re getting bigger and taller, but they’re being built on ever smaller lots. This is in contrast to the low slung horizontal tract homes with generous gardens from past decades. Even when these new neighborhoods are in locations with relatively moderate land values the infrastructure costs are forcing the design shift. All the pipes, wires, pavement, support systems, permits, impact fees, and associated soft costs have to be rolled into the sale price of each finished unit. Compared to 70 or 50 or even 30 years ago these expenditures are significantly more pronounced.

There’s a hard limit on what people can pay for a house, but also unyielding must-haves and won’t-tolerates that have to be respected. So the front lawns shrink to a tiny personal parking lot with a green toupée of token grass to convey middle class respectability. The back gardens tighten up to decks with horse blinder side fences overlooking a shared drainage ditch. The homes get tilted up like boxes of cereal and the result is approaching a traditional urban row house format. It’s just been modified to accommodate four cars per family minus the commercial elements and urban amenities found in an older town. This is what I call density without urbanism.

Images via Google.

While suburban expansion is formulaic and dominated by deeply engrained cultural demands, urban redevelopment in the city center is equally predictable. I poked around past incarnations of Halifax’s old master plans for economic advancement and was underwhelmed.

In 1995 the Halifax Casino was opened as part of a larger vision to induce jobs and goose tax revenue through tourism—preferably from visitors from outside the province. The money drives down the highway, parks in multi-story decks, walks through elevated glass skyways and tunnels to hotels, hits the restaurants, shops, office towers, and casino, then drives back home to be a burden on someone else’s municipal budget. And it all pays for itself!

These two signs on either side of the highway sum up the zeitgeist pretty well: “Welcome To Historic Properties.” and “Marriott Access Only Beyond This Point.” Notice the middle aged couple on the sidewalk halfway between the hotel and the parking deck across from the highway wall. They only have one option. Go back inside. That’s a feature not a bug. The old downtown waterfront is a commodity to be consumed and a private realm to be enjoyed by paying clients. It’s been a mere 25 years and the whole thing is already out of fashion and coming to the end of its lifecycle with declining revenue and increasing maintenance costs. Turns out, every town on the planet now has a casino, an aquarium, a convention center, an international trade center, at least one over-scaled sports venue, a performing arts center, etc. More than a few are now stranded assets in a saturated market.

Image via Google.

Image via Google.

I found the newest master plan for the Cogswell District. Before I opened the documents I made a checklist in my mind of what I thought it might include: Replacing the old highway with a linear park, a bike trail, pedestrian plazas, a few traffic calming roundabouts, new links to the waterfront, and some shiny high rise towers. Toss in some solar panels, windmills, bio-swales with native plantings, and abstract plop art. Check out the video and see how close I got. I’m not opposed to any of these things per se. But I’m clear about what it’s all about.

Halifax is trying to attract a well educated demographic with disposable income and an appreciation for urban amenities. Sidewalk cafes, pop up shops, farmers markets, and upscale condos are the latest version of the casino. And all the usual players are on board. The engineering firms, the financiers, the companies that sell concrete, steel, and glass, the labor unions, the provincial apparatchiks, and the local business associations all want this plan to be as large, complex, and expensive as possible. These are precisely the same folks who built the casino a generation ago. And this plan pays for itself! If Halifax is really lucky it might mimic the success of Toronto and Vancouver in miniature, but that model is a curse as well as a blessing.

I noticed Halifax has a star shaped military fortification that dates back to 1749. The same design was used in the founding of new settlements all over North America around this time. They were based on more elaborate citadels built earlier in Europe going back to fifteenth century Italy. Michelangelo designed one for Florence, in fact. They too were formulaic. Find high ground. Dig a moat. Use the excavated dirt to build up mounds. The star shape created funnels so invading forces could be surrounded on either side as they approached. The interior provided secure space for housing, supplies, and munitions. They were the ultimate development vehicle of their day—the mega-mall or casino or tax holiday production zone. This model was repeated until weapons and military tactics made them obsolete. Most were eventually subsumed into the urban fabric or abandoned into ruins.

Image via Google.

This gets us back to the Bayer’s Lake site and the grad student’s project. At the moment nearly everything that’s built nearly everywhere is constructed by a handful of players. There are exactly 19 standard real estate “products” each with its own specific parameters and institutional ecosystem. There’s the garden apartment complex, the high rise condo tower, the strip mall, the office park, the single family home subdivision, the retail power center, the light industrial complex, the mobile home park, and so on. Building absolutely anything that doesn’t fit neatly into one of these categories is exceptionally difficult.

It’s entirely possible to craft a master plan that uses these standard products like Legos to build a tolerably walkable bike-friendly green neighborhood. I’ve seen this done reasonably well elsewhere. But to be really effective each of the separate property owners as well as the municipal authorities have to be on board. It’s like herding cats. And city officials will always choose the plan that creates short term employment and tax revenue at the expense of long term solvency and sustainability.

Bayer’s Lake was originally established as a commercial and light industrial zone. It isn’t special enough to become much else without heroic effort and a mountain of money that probably doesn’t exist. So embrace the zone for what it is. It’s right next to the Trans-Canadian Highway. Halifax has a deep sea port, a railyard, and an international airport. The university continually churns out smart young people. And the Maritimes are the least expensive region in Canada.

So, create a municipal zoning overlay that prioritizes the kinds of warehouse distribution centers that are putting physical retail out of business. As the existing stores die (and they will) the owners will have an easy path to sell off their empty husks in favor of distribution warehouses. To keep things diversified have the city woo some back office support centers with Halifax’s smart, but moderately paid labor force. And see if the province can’t induce some server farms with the lure of cheap bulk hydro. Rebrand the district “Tech Lake Center.“ This will buy the area some time until the next New Thing materializes in a couple of decades. It’s not pretty, but that’s how these things tend to go.

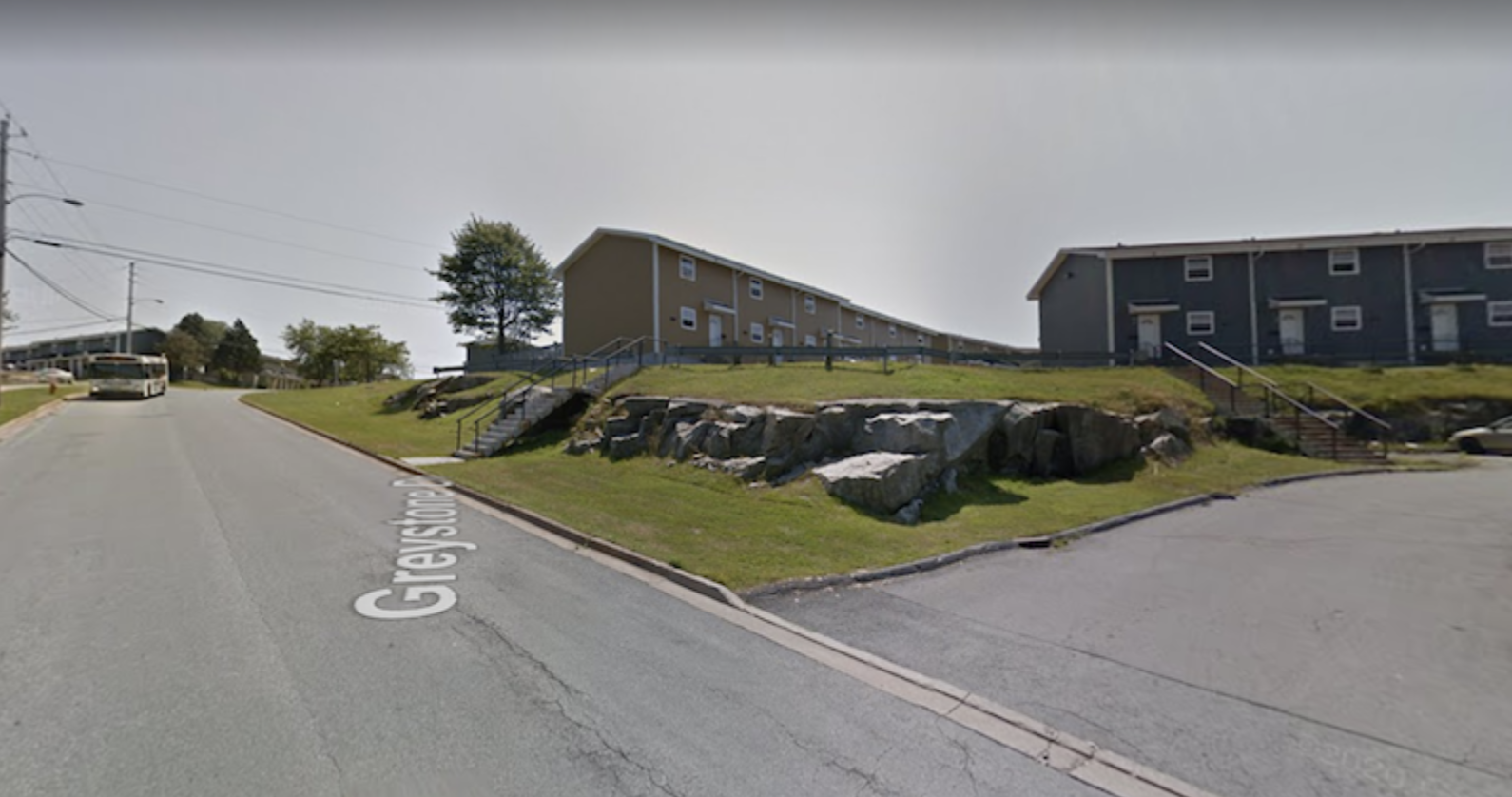

I’ll leave you with these images from the Metropolitan Regional Housing Authority. It’s a textbook “train wreck” apartment complex—named after what they look like from the air. As is so often the case this government subsidized housing is way out on the edge of town next to absolutely nothing. I see the bus makes its trek to and from civilization. I checked the schedule and, after hours, around the time an employee at Bayer’s Lake might need to get home after work, it’s an hour journey for a trip that should take fifteen minutes in a car. These are the choices society tends to make. But in this mediocre place planned with poverty in mind people are adapting. I love the little rubber pool filled with a garden hose enjoyed by the neighborhood kids. There’s nothing more ecological than drying clothes on a line in the sunshine. These are the pragmatic solutions that people come up with when they don’t have masters degrees in urban planning and lack multi-million dollar budgets for implementation. And it works…

Images via Google.

Cover image of Halifax via Pixabay.

Officials in Ottowa, Canada, are showing that local governments don’t need to accept expensive and unproductive projects, even if they have a lot of momentum behind them.