The Roots of a Resilient Small City Economy in Durango

The history of modern Colorado, like much of the American West, plays a significant part the history of mining. The hunt for gold, silver, lead, tin, and so on was what motivated many of the expeditions of white settlers into the state's forbidding mountain passes and valleys in the nineteenth century.

Durango, in the southwestern part of the state, is no exception. Its early history was shaped by railroad links to mines throughout La Plata, San Juan, and other counties, and by the resultant presence of the Durango Smelter, which processed minerals extracted from those mines until the 1930s.

Main Avenue in Durango, Colorado. Image via Flickr.

But every place where the economy is premised on the exploitation of a finite, non-renewable resource eventually reaches a point where it must either adapt or die. In that, Durango's highly successful adaptation makes it a powerful model of what the future could look like for former or present mining communities throughout the region.

A city of 17,000 people in a county of 51,000, Durango is now known as a tourist town—leveraging its renewable resource of mountain views and skiing and hiking opportunities. The former site of the smelter is a dog park, and the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad, recognized for the spectacular scenery along its route, hauls sightseers instead of silver ore.

But even tourism poses challenges for growing a resilient and diverse economic base. Tourism is a cleaner, greener version of the resource economy, but it doesn't wholly address the question of whether the community is building its own financial productivity, and developing in a way that can sustain that productivity over time.

We know what that looks like from doing the math on where hundreds of communities are drawing the majority of their wealth and jobs. The answer almost always involves a compact, walkable, strong downtown core that anchors the community. And it involves nurturing a robust ecosystem of local businesses that will generate prosperity and keep the proceeds at home.

In Durango, they've been making the investments in downtown and in locally generated prosperity that they need to make. And we can see what it looks like when those things start to pay off.

The Numbers Don't Lie: Downtown is Potent

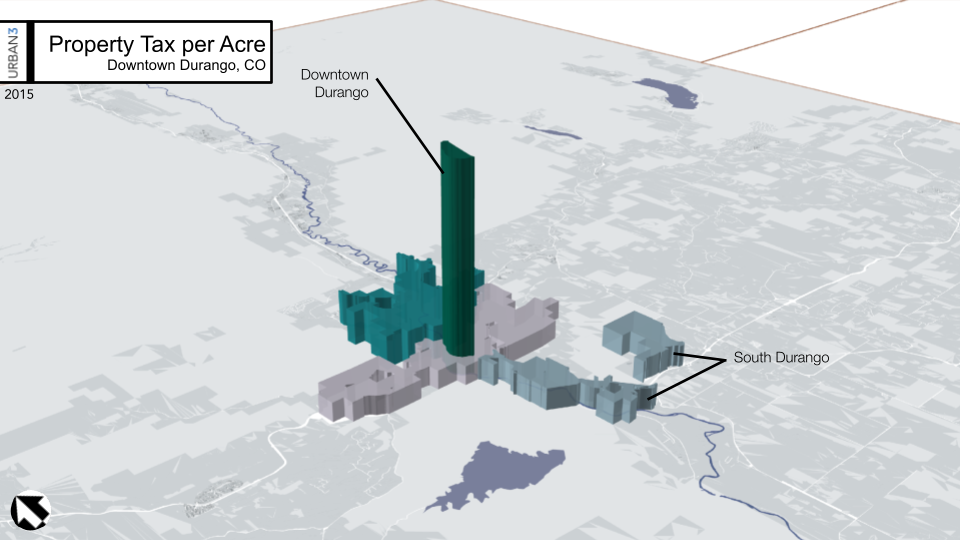

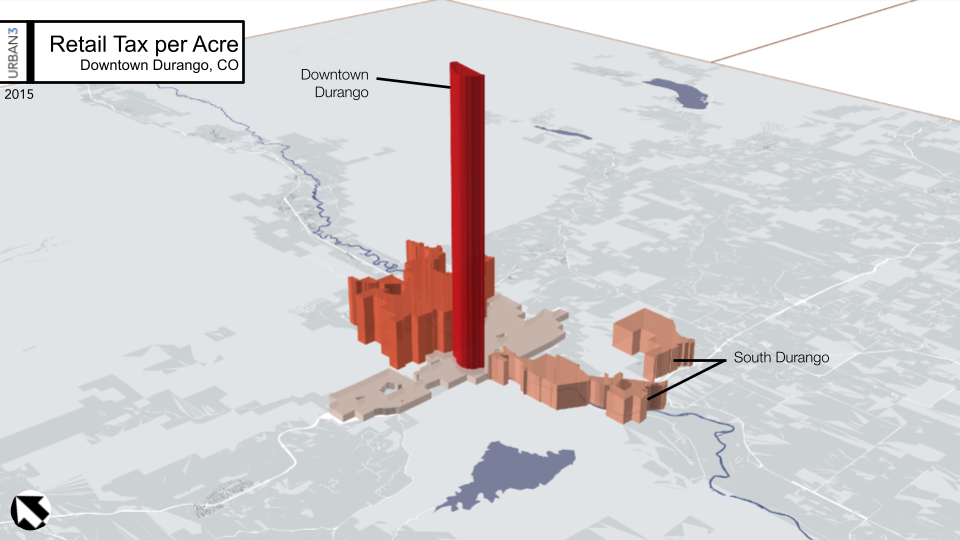

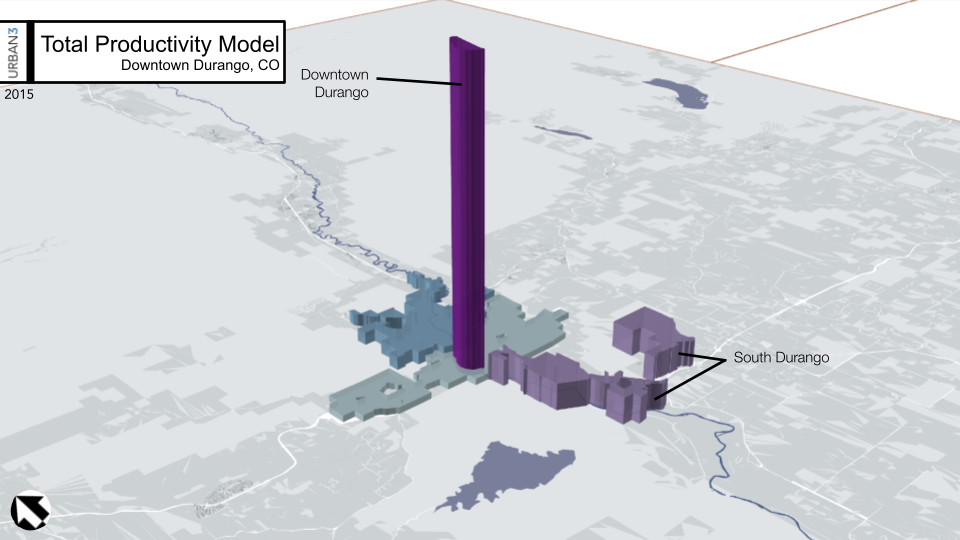

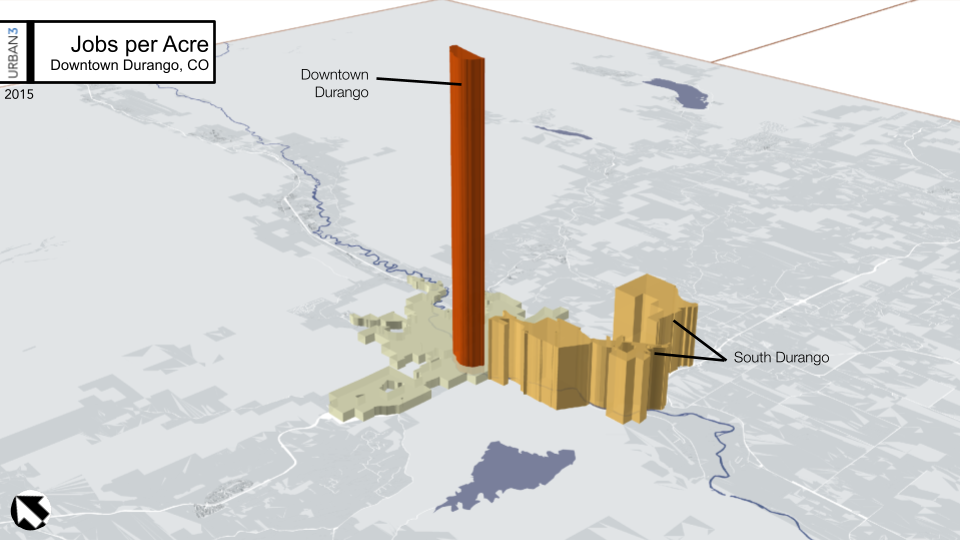

In 2015, the geoanalytics team from Urban3 paid a visit to Durango and did an analysis of property and retail tax revenue generated by area of the city. Urban3's work in Durango demonstrates the power of a strong downtown anchor, as usual. But it also contains a couple of interesting findings that might surprise.

One is that we can dispel the myth that the sales taxes generated by chain and/or big-box retail are such a boon to communities that they override the low property tax value generated by these stores. In 2018 we wrote about how, in fact, retail tax revenue in Durango closely tracks sales tax revenue, and is much higher on a per-acre basis in the walkable downtown dominated by local businesses than in South Durango, which is dominated by automobile-oriented chains:

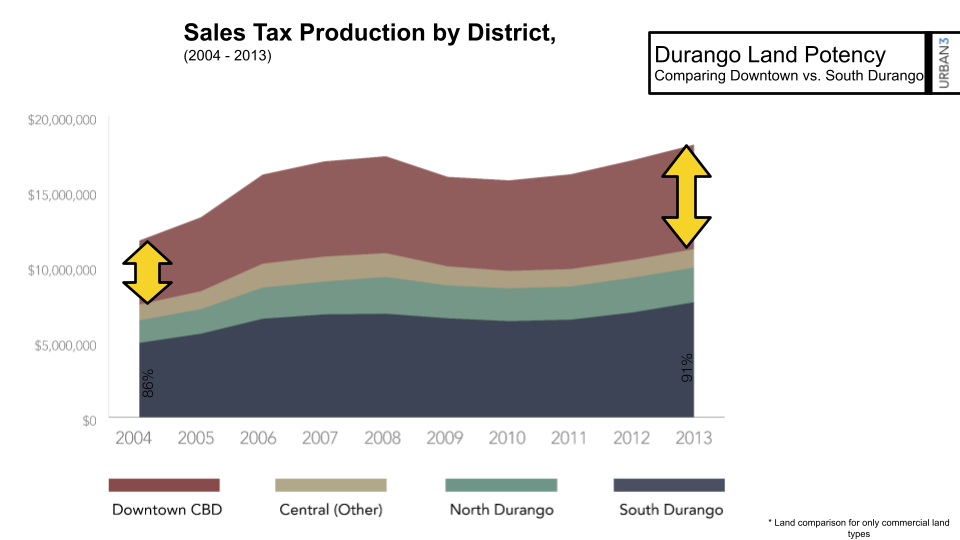

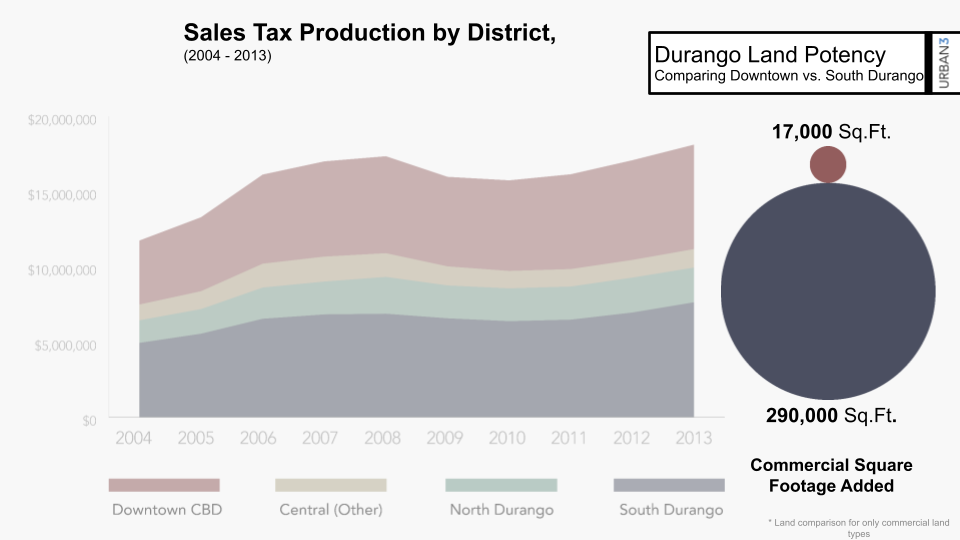

The other interesting tidbit from the Durango data comes when we examine the trajectories of different areas of town over the course of the Great Recession and the years leading up to it. We can see what appears to be a modest but steady growth in sales tax production in both the walkable downtown and the auto-oriented south side, with a slight dip during the recession, followed by recovery. That being said, though, how much new retail space did each of those areas add between 2004 and 2013? The answer is only 17,000 square feet downtown, versus nearly 300,000 in South Durango. It's not infill development that is driving downtown's fortunes, it's the potency of what is present there.

What's going on downtown is the success of a local business ecosystem, not just a few successful businesses. As Joe Minicozzi of Urban3 put it to me, when you think about the owner of the downtown coffee shop or bookstore versus the Starbucks down the highway, "Who's using a local accountant? Who's using a local print shop? Who's sponsoring a little league team?"

Local business owners are more apt to support each other by using local services, but they're also more likely to explicitly cooperate toward shared goals. I spoke with Peter Schertz, who operated Maria's Bookshop on Main Avenue for 21 years before passing ownership on to his son Evan in 2019.

Schertz told me that Durango has a strong and very functional business improvement district. The BID, he said, helped during the pandemic to ensure that merchants had access to personal protective equipment, and sponsored events such as gift-card raffles to keep up customer interest in downtown. COVID-19 was not Durango businesses' first brush with banding together to withstand a crisis. In the summer of 2018, the 416 Fire caused the evacuation of the town and did massive damage to the area's tourism industry. In the recovery from the fire, the BID was an invaluable resource for identifying needs and helping them get met. According to Schertz, the Chamber of Commerce is also a champion for downtown and local businesses, and the tourism office collaborates well with the downtown BID.

The city government has also been willing, often at the request of small businesses, to reassess the public space of the city and how it's serving the community. While Durango still struggles with the effects of stroads built in the peak era of automobile ascendancy—including a four-lane Main Avenue—the city has been using bump-outs to calm traffic and encourage more pedestrian life.

Durango has also been willing to roll with the times. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the city established a grant program to fund the creation of parklets for businesses to offer safe outdoor space for their patrons. Under the program, the city would match up to $3,000 in private funds raised for such projects. Schertz estimates that Maria's bookshop put in over twice that in its own funds, producing a pleasant, green, and lush ("I'm a big tree and shrub guy") oasis for patrons to read and linger.

Moving Beyond Local Consumption

Durango has the problems that afflict most tourist towns. There are severe issues with affordable housing for the local workforce, even as newly remote white-collar workers from larger cities such as Denver move to Durango full-time. Wages in the service industry are low, and economic activity is seasonal.

Durango isn't going to deliver a high quality of life to full-time locals purely on the basis of tourism. The next step in economic development is to look outward: what can we produce locally that we can sell nationally?

SCAPE, the Southwest Colorado Accelerator Program for Entrepreneurs, is an award-winning program based in Durango that aims to help find and empower the people with good answers to that question. Locally based companies whose customer bases are nationwide can enroll in SCAPE's six-month program, where founders will learn "customer-oriented product development, product marketing operations, and finance from experienced executive experts." SCAPE aims not only to mentor founders, but to invest in these companies enough to give them a year or two of runway to scale up their operations. Eight years old, SCAPE has raised $25 million in capital and launched 36 companies worth a total of $170 million.

Elizabeth Marsh, the Executive Director of SCAPE, explains that SCAPE focuses on companies that sell their goods, services, or technology outside the region, because those tend to create higher-paying positions for community members. Also, they are more insulated and able to weather seasonal economic fluctuations and downturns. During the COVID-19 pandemic, none of the SCAPE companies had any layoffs, because their businesses were already geared for remote sales.

The first company in the Southwest to sell cross-laminated timber (CLT) for construction was founded in Durango and participated in SCAPE’s accelerator program. Image via Flickr.

SCAPE has seeded Southwest Colorado-based companies that include a mountain-bike components manufacturer; a cross-laminated timber producer (first in the Southwest); and a company that "does web-based case tracking and grant management software used by crime victim advocates"; among many others. A lot of SCAPE's mentors and investors are wealthier, older second-home owners who have chosen Durango for its quality of life and outdoor amenities.

Similar to economic gardening (an approach developed on the other side of the state in Littleton), SCAPE's accelerator model seeks to build on the forces of innovation and ingenuity already present in the community instead of luring it from outside. "We don't really believe in recruitment or incentives," says Marsh. The incentive packages required to lure a larger business to a small rural community with a small workforce and, often, a lack of affordable housing, are unreasonable when not totally laughable, and are generally a losing proposition. But many of these places do have entrepreneurial people who would like to live, and remain, in the community. The key is to help them get off the ground floor.

I asked Marsh for her advice to communities that don't already have the things Durango has going for it, specifically Colorado towns trying to transition from an extractive economy to the kind of generative one that SCAPE is helping to build. Her answer: "The most important thing is that you start immediately. I think people need to be prepared for how long it's going to take."

Small towns trying to escape the curse of dependency on a dying resource economy can find themselves in a catch-22: They desperately need economic development, but who is going to pay for it? With a declining property tax and sales tax base, sometimes communities find it impossible to fund and support the efforts now that could be transformational in the future.

The response to that is to get everyone at the table. Diversifying and strengthening your local economy is a community effort, involving the public, private, and nonprofit sectors. It's a long, patient one, and there's no single road map: you need to identify needs incrementally and respond and adapt to them.

When you start to develop an ecosystem of local innovators and producers who have a deep commitment to place, though, you can really begin to grow something remarkable.

Cover image via Flickr, with edits.

Daniel Herriges has been a regular contributor to Strong Towns since 2015 and is a founding member of the Strong Towns movement. He is the co-author of Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis, with Charles Marohn. Daniel now works as the Policy Director at the Parking Reform Network, an organization which seeks to accelerate the reform of harmful parking policies by educating the public about these policies and serving as a connecting hub for advocates and policy makers. Daniel’s work reflects a lifelong fascination with cities and how they work. When he’s not perusing maps (for work or pleasure), he can be found exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods on foot or bicycle. Daniel has lived in Northern California and Southwest Florida, and he now resides back in his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, along with his wife and two children. Daniel has a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota.