"Another Kind of Piñata You Can Be"

Pueblo, Colorado is blessed with a remarkable natural setting. It lies near a spot where the Arkansas River emerges from the canyon it has gouged through the jagged peaks of the Rocky Mountain Front Range onto the endless sweep of the High Plains, beginning its long, slow descent toward the Mississippi. Pueblo is the southern anchor of the booming Front Range megalopolis, and you’d be forgiven for assuming it has shared in the recent economic dynamism of its cousins like Denver and Boulder.

But Pueblo is curiously unlike much of the region in its history and economy. In fact, it has more in common with Rust Belt cities over 1,000 miles to the east. For most of its history, Pueblo was a steel town. The city’s dominant employer was the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, for decades the state’s largest employer. CF&I owned not only the Pueblo steel works—a magnet for immigrants and other blue-collar workers from throughout the U.S.—but a whole network of iron, coal, and other mines throughout Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah.

The story of steel in Pueblo is long and I won’t tell it at length here. The industry underwent the same decline, for many of the same reasons, as Pittsburgh and other steel hubs. In 1984, the steel mill issued 6,500 pink slips in a single day, according to a recent NPR profile of Pueblo and its changes. Today, the CF&I steel operation is owned by a Russian company, and most of the jobs have been automated away: only 6% of Pueblo jobs are in manufacturing.

But even as these economic changes buffeted Pueblo, a different kind of growth industry was taking shape: one that is, in its own way, no less extractive and fragile.

Pueblo’s Bizarre Suburban Experiment

A community losing its primary manufacturing base, with job and wage growth significantly below the state average, should not be a good candidate for massive suburban expansion. From 1960 to 1990, the population of Pueblo County barely budged at all. But Pueblo County had mountain views and wide open spaces, and plenty of cheap land to be sold and speculated upon. And so, in 1969, along came Pueblo West, described by its founder as a “pioneering,” “multi-million dollar investment to transform nearly 26,000 [acres] of rich rangeland at the base of Colorado’s teeming front-range strip into a city for 60,000 people.”

An aerial view of part of Pueblo West, Colorado, from Google Maps reveals the sparseness of the development pattern.

A half-century later, Pueblo West has roughly 32,000 inhabitants, not 60,000. And to call it any sort of “city” is a stretch. Pueblo West is something altogether stranger. Unlike most suburbs, which grow around the periphery of their core city, Pueblo West is barely contiguous at all with the city of Pueblo. It appears on the map as a wholly separate blob, spilling out onto the rangeland along U.S. Highway 50 up toward the mountains. Pueblo West is mostly residential, and very sparsely populated, but crisscrossed by an extensive network of streets and sewers all the same.

Photo via Urban3.

It’s also not a legal city, even 50 years into its existence. Its quasi-government, the Pueblo West Metropolitan District, has the authority to collect property taxes, but does not provide the full suite of services that an incorporated city would: things like law enforcement and libraries are the responsibility of Pueblo County. The school district is also a separate entity (which is not unusual in America, even for incorporated cities).

Pueblo West has attributes that will be familiar to those who know the likes of Lehigh Acres or Palm Bay, Florida; California City, California; or Lake Havasu City, Arizona. All of these, among others, had their origins as speculative land development schemes in the loosely regulated 1960s. In all of them, developers subdivided and paved street grids across truly massive expanses of empty land, selling off the individual lots to homebuyers with little thought to planning for long-term infrastructure, a public realm, or a sustainable economic base. In all of them, many lots have sat undeveloped for decades, and most of the actual population growth has come only since 1990 or so.

(Pueblo West’s original developer, Robert McCullough, was a colorful character who made his fortune in the chainsaw—yes, chainsaw—business. He was also the developer of Lake Havasu City, where he famously pulled off the stunt of transplanting and reconstructing an 1831 stone bridge from London, England. If you’ve ever been informed, as a matter of trivia, that “London Bridge is in Arizona,” you have McCullough to thank.)

Graphic via Urban3.

The defining feature of Pueblo West is that it is huge: 70 square miles. That is 56% larger than Pueblo itself, for only 27% the number of inhabitants. (Numbers in this graphic are from the 2010 census; a more recent estimate has the population of Pueblo West slightly larger, at 32,000.)

Pueblo West is sparsely populated, but because its infrastructure was created far in advance of any sort of build-out, to this day there are whole blocks with only a few scattered houses. Commercial activity is centered on U.S. 50, and what is there is largely chain retail.

Pueblo West has 400 miles of road. If it is not readily obvious how excessive this number is, consider that it comes to 66 feet of road per capita. Compare this to, for example, 10 feet per person in Miami, Florida; 28 feet in financially strapped Kansas City, Missouri; and 46 feet in Palm Bay, Florida—a vastly overbuilt city that was developed in a very similar way to Pueblo West.

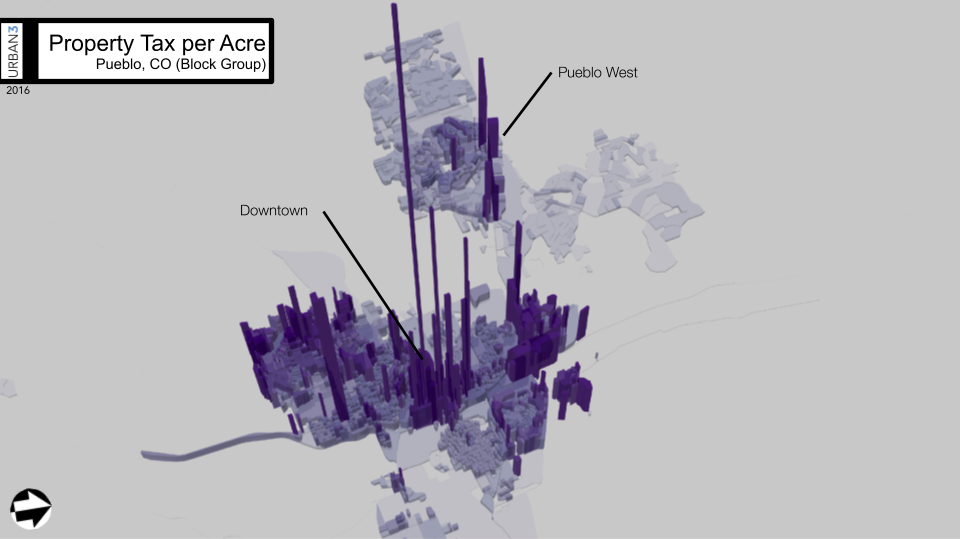

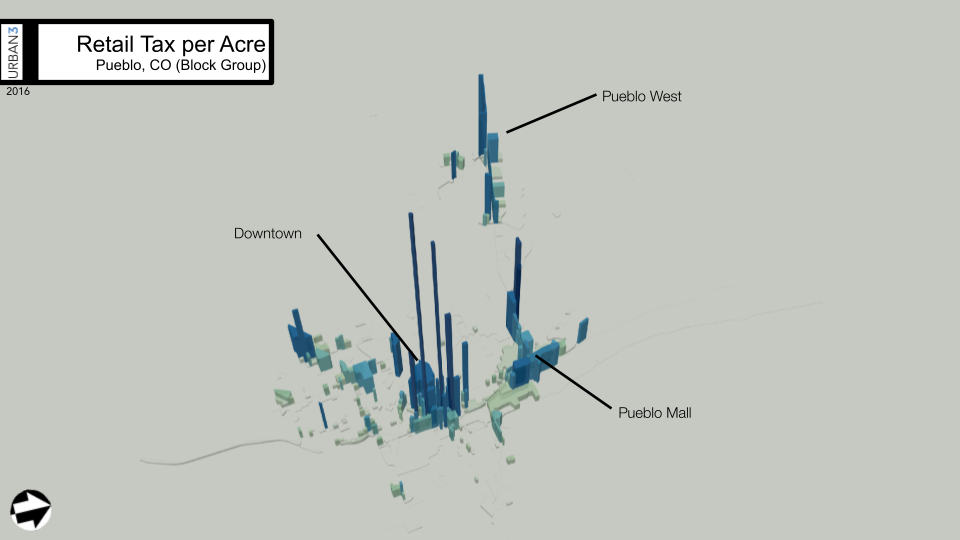

If the disparities in population and infrastructure are striking, the disparities in the economic base available to fund that infrastructure and the needed services are even starker. Data from geoanalytics firm Urban3 examine Pueblo County’s property and retail tax revenues on a per acre basis, comparable to the way you might measure your car’s fuel efficiency in miles per gallon. This reveals that Pueblo West brings in far less revenue from either source than the city of Pueblo, and is particularly less productive than Pueblo’s core downtown. (It’s worth noting that retail tax revenue does not go directly to the Pueblo West Metro District; it goes to the State of Colorado and Pueblo County.)

What part of Pueblo County outperforms financially? As is the case in city after city, large and small, the greatest concentration of taxable value is found in downtown Pueblo, the area developed on a compact, walkable pattern prior to the age of automobile suburbs. Downtown is represented by several tall “spikes” on the above maps. Even though Pueblo is not the economic powerhouse that other Front Range cities like Boulder or even Colorado Springs can claim to be, its compact, walkable core still brings the goods.

A side-by-side comparison of two buildings is enough to illustrate what this difference looks like on the ground: a single small mixed-use building in central Pueblo, the Union Ave Palms, generates more than ten times the property tax value, on a per acre basis, that is brought in by the 56-acre Pueblo Mall. It’s two stories of housing over retail, but it represents one template that works, and that can be repeated again and again.

Another Extractive Industry?

Pueblo’s economy is showing signs of turning a corner. The region has embraced clean energy industries, as well as marijuana tourism following its legalization in Colorado in 2012. However, deindustrialization’s toll has been steep. The countywide poverty rate remains a stubborn 19%; in the city, the figure is 23.5%. And while population growth has returned since the 1990s, much of it has occurred in cheap, low-tax Pueblo West, representing a drag on the region’s potential.

Joe Minicozzi of Urban3 describes Pueblo County as illustrative of “another kind of piñata you can be.” Communities dependent on natural resources, like Pueblo once was with the dominance of Colorado Fuel & Iron, are batted around by economic forces largely outside their control. But in embracing a speculative suburban growth model, the region may have traded one extractive industry for another.

Suburban development is, of course, not an extractive industry in the same way that iron or coal is, but in many ways, “extractive” is an accurate descriptor. The development of a place like Pueblo West is a one-time shot. It produces an initial windfall out of those sweeping views and wide-open spaces. It leaves behind a development pattern that can’t pay for its own maintenance in subsequent generations. Undeveloped land is a non-renewable resource. And all those chain retailers lining the highway aren’t keeping their profits in town.

The Arkansas Riverwalk in downtown Pueblo. Image via City of Pueblo

What Pueblo needs is a development strategy that builds local resilience, an economic base that isn’t reliant on a single industry or employer as was the case in the steel era. And it needs a physical development pattern that is conducive to this, concentrating local wealth and fostering local entrepreneurs. This means working to redirect growth toward the already-productive core neighborhoods, and eliminating perverse incentives for businesses (and new residents) to locate outside city limits.

Otherwise, the growth of Pueblo West is at best going to be a drag on those efforts, by dispersing the county’s population away from the city center, and imposing massive public service costs on its taxpayers. Minicozzi warned Pueblo leaders as much in a 2016 visit:

“It’s just going to drag the whole county down in the process….. You see the moonscape of empty space. It’s just not going to ever achieve the value of even the North Side of Pueblo.

The numbers are there to tell us exactly what we have to be doing. You just have to do the math.”

Officials in Ottowa, Canada, are showing that local governments don’t need to accept expensive and unproductive projects, even if they have a lot of momentum behind them.