Crime Scene Photos

One of the most enduring myths about North American cities goes something like this: "It’s such a shame we Americans didn't build our cities to have nice walkable neighborhoods, narrow streets, and human scale buildings, the way they did in other parts of the world."

The thing is, we did do that. We just deliberately destroyed a lot of it.

There is a lot that has already gone down the Memory Hole about just how destructive the post-World War II era really was for American cities. We did a better job of wiping out portions of our own cities than a full-scale war ever could have. We did it through Urban Renewal, and we did it through freeways. Of course, the two often operated in tandem, with the construction of a new highway providing a convenient excuse to condemn and clear land that the local government—in thrall to the new twin ideologies of car-centric expansion and hyper-orderly, modernist planning—wanted to redevelop.

The war analogy was not lost on the people alive at the time. In Kansas City, for example, citizens likened downtown freeway construction to the London Blitz.

Much more of the historic fabric has been lost to the depopulation and disinvestment that plagued the inner cities in the 1950s through 1980s, leaving many communities shells of their former selves. Businesses gradually gave way to vacant lots and parking, homes to abandonment, decay, and demolition, until whole streets and neighborhoods were unrecognizable. There are places in nearly every major U.S. city where the job was so thorough that few who are alive today can remember the lively buildings and streets that used to stand where there is now an interchange, convention center, or parking lot—and almost as few know they were ever there.

Sanborn Maps as Crime Scene Photos

Do you have to be a professional historian, tracking down and poring over dusty archival photos, to start digging into what once was and what could have been? No: there's actually a widely available and fascinating resource that anyone can use to answer these questions. I’m talking about Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps.

For decades, long before computers and GIS, the Sanborn company had a monopoly over the maps used by fire insurance companies to tally and estimate their total liability in fire-prone urban areas. They began to be published in the late 19th century, and the last one was released on microfilm in 1977. These maps contain detailed information down to the block level, clearly depicting and identifying individual buildings in approximately 12,000 U.S. cities and towns.

Today, old Sanborn Maps are a fascinating resource for examining forgotten portions of our cities. The Library of Congress has a very large collection of these maps accessible for free online. Full sets typically include an index map allowing you to identify the specific map number corresponding to an area of a few blocks you want to examine. Many university libraries and local historical institutions also have collections, though some of these restrict access.

Think of Sanborn Maps as crime scene photos, depicting the productive and full places that were hollowed out or deliberately bulldozed in the name of supposed progress. Imagine what many of these streets could hold today, had they been left to incrementally mature. Buildings seen as obsolete relics in 1960 would have been prized in 2020, when the scarcity of walkable urban neighborhoods means that Americans will pay a hefty premium to live, work, or shop in one. Especially one with historic character.

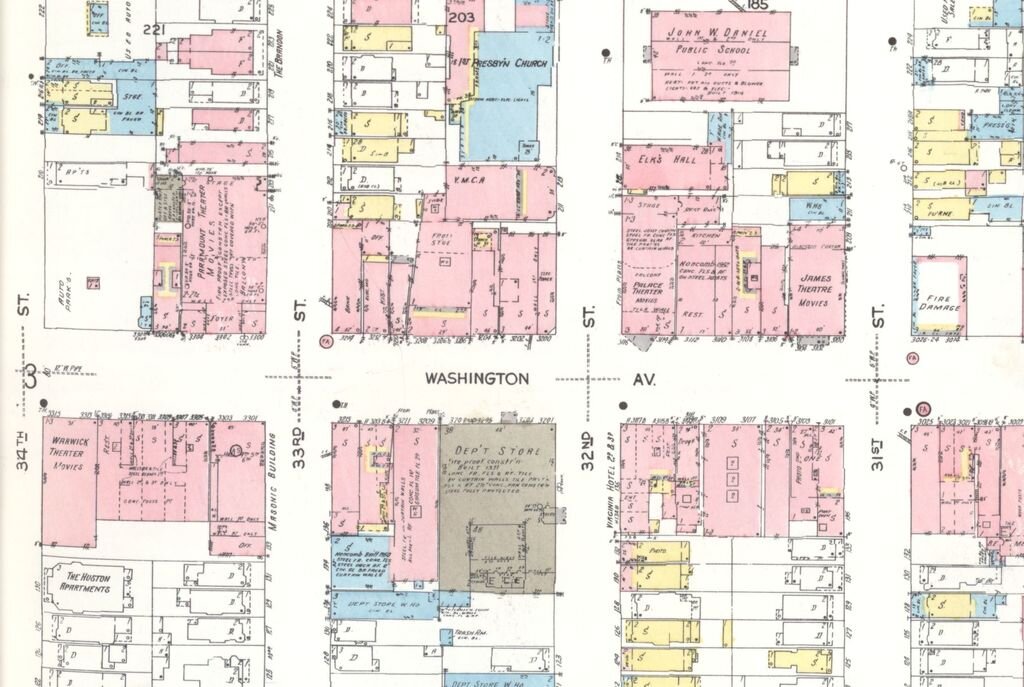

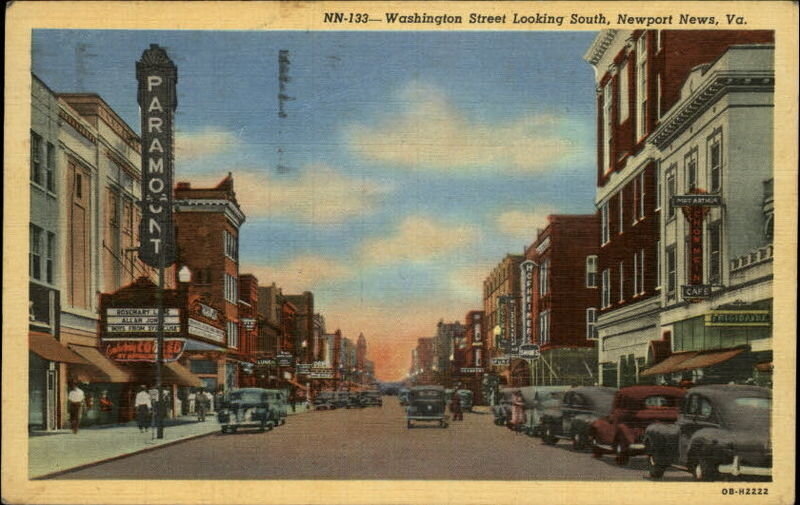

Did you know that Newport News, Virginia, used to boast a bustling theater row? You can see it in old postcards, and Sanborn Maps from 1926 confirm a cluster of theaters along Washington Avenue with names like the Paramount, Warwick, James, and Palace. Today you’ll find a less-than-striking mix of parking lots and garages, vacant land, and some recent superblock redevelopment.

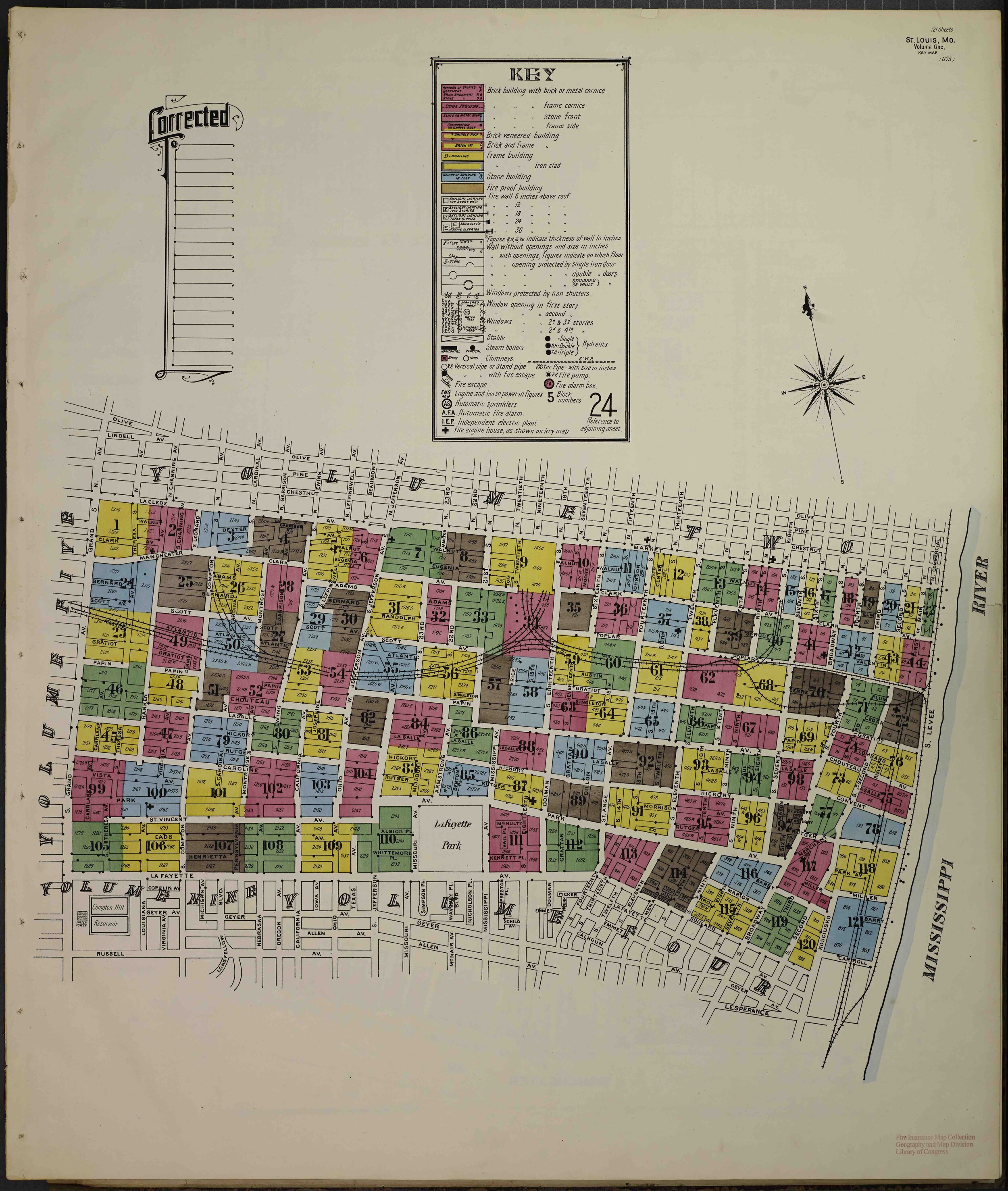

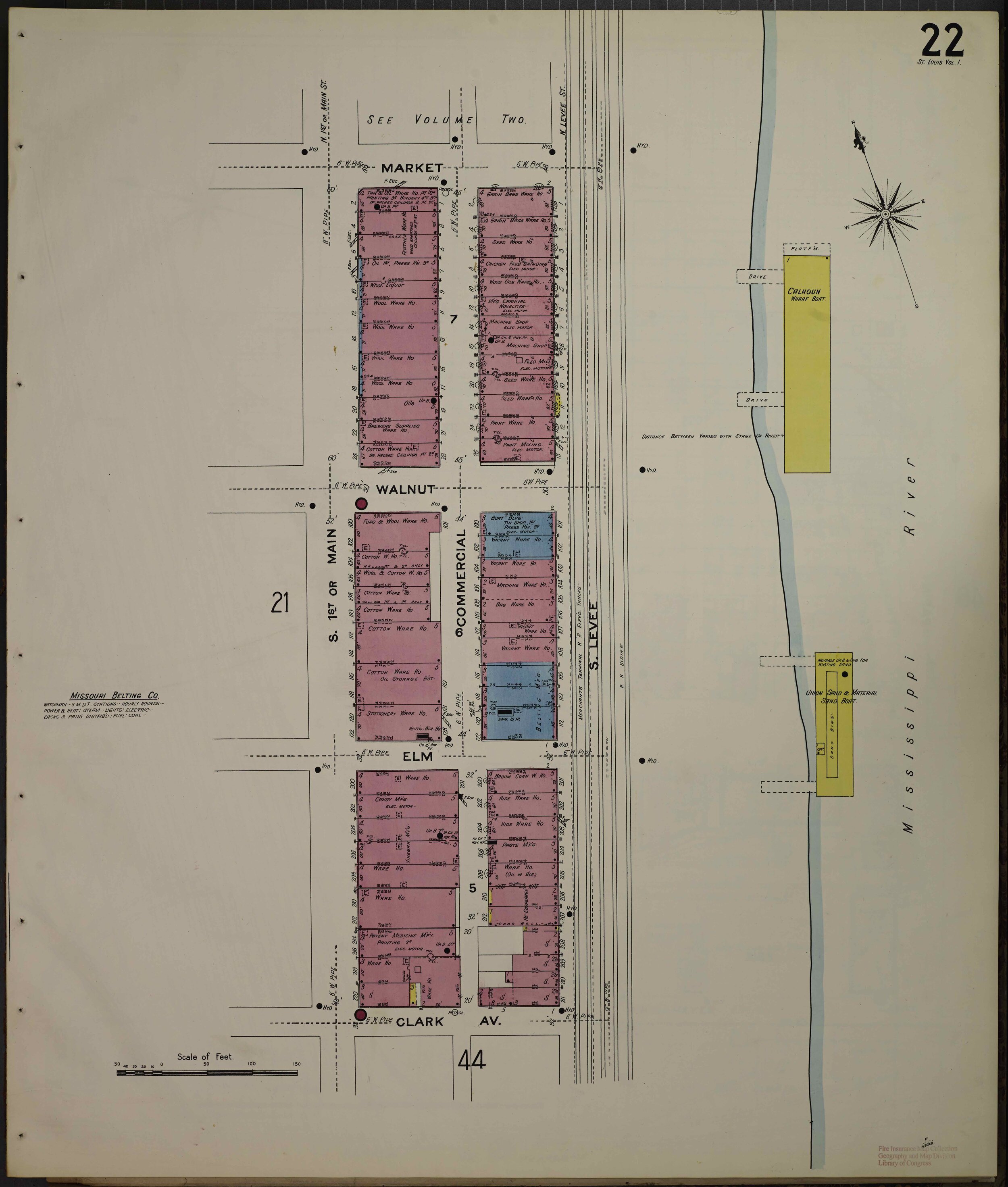

A whole St. Louis neighborhood some have compared to the French Quarter was condemned and leveled for what would become the Gateway Arch. Photos show the shocking transformation, and Sanborn Maps allow you to dig into the details. In 1908, zooming in on a waterfront block directly south of where the arch now sits—bounded by Market, Clark, Main, and Levee—we find warehouses for furs, wool, cotton, seeds, candy, and hides. Photos from shortly before the 1939 demolition reveal a dense grid filled with elegant architecture. Imagine the value of these buildings today had they not been destroyed but rather repurposed for housing, as has been the fate of so many other American warehouse districts in recent years.

In Minneapolis, Minnesota, the construction of Interstates 94 and 35W left a patch of land on the edge of downtown unrecognizable. Several dozen whole blocks were obliterated, in the process condemning the adjacent Phillips neighborhood to years of decline and poverty, cut off from downtown by an imposing moat of cars. A small sampling of the leveled blocks contains private houses (many of them duplexes) and some apartment buildings, along with a bakery, a dry cleaning shop, and a funeral home, all visible on the 1912 Sanborn map:

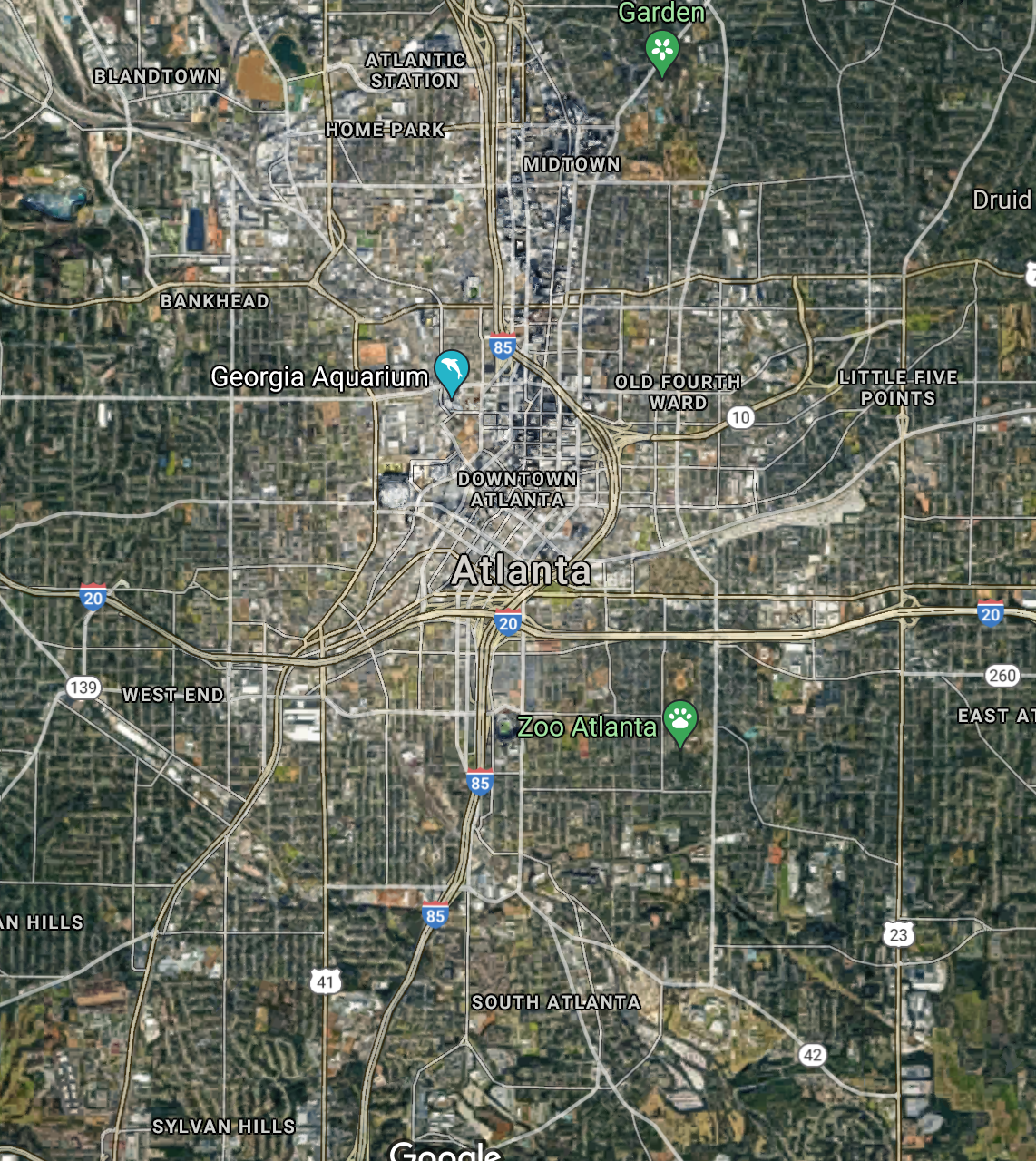

Freeways and urban renewal so transformed central Atlanta, Georgia’s street network that looking at a Sanborn map from 1911 is utterly disorienting: even the major streets then don’t seem to correspond to major streets now, as many have been rerouted and/or renamed. Once you get your bearings, the scale of the destruction is shocking:

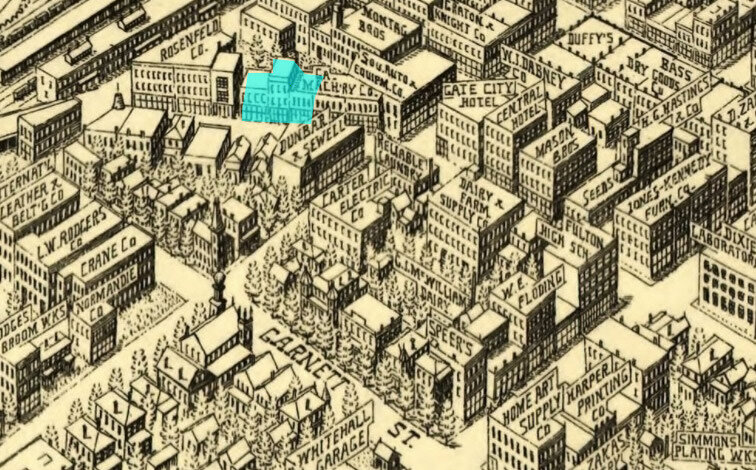

Atlanta activist Darin Givens has written about Atlanta’s forgotten urbanism. In one comparison on his blog, Givens finds a multi-block area in which only one cluster of three small buildings is still standing, although a 1919 illustration depicts a thriving urban district along an intricate grid of streets such as you might find in London or any other great city:

Here’s the 1911 Sanborn Map view of the same area. Buildings labeled on the map, centered on the intersection of Forsyth and Trinity, include a print shop, a stationery manufacturer, the Gholstin-Cunningham Spring Bed Company, Georgia Hand Laundry Company, National Straw Hat Works, Little Gem Hotel, and Trinity M.E. Church South.

Naturally, businesses will come and go. The real crime here is that not one of those buildings is still around. the neighborhood has been sacrificed on the altar of free parking.

Remember, So as Not to Repeat

I’m writing this on May 4th, which happens to be Jane Jacobs’s birthday, and which Strong Towns has for that reason suggested as a fitting date for Urban Renewal Remembrance Day. This would be a day for planners, engineers, or anyone involved in the building or design of cities, to set aside some time for solemn reflection on the hubris of the past and what was lost forever because of it. It’s also a chance to renew a personal vow to practice your work with humility and respect for the complexity of cities, now and in the future. Our places are strongest when they’re built and improved by many hands, but they can be undone by very few.

Reflection starts with remembering. Maps are but one vital tool for us to do so.

Today, Abby is joined by Bernice Radle, a small-scale developer and historic building preservationist from Buffalo, New York. They discuss how two developing news stories could affect both small-scale developers and historic preservationists.