What Is Wealth? How Do We Make It?

My daughter just turned one year old. In ten years, when she’s curious about what the world was like when she was born, the pandemic will be front and center, obviously: a global event that ricocheted through public health, the credit markets—pretty much everything. “Unprecedented” got thrown around a lot, whether describing Congressional appropriations running to trillions of dollars, or the loss of life, a number that in the United States, surpassed World War II combat deaths, reducing population life expectancy by more than a year.

Image via Unsplash.

That’s the bad news. The good news is what happened next: the global vaccination campaign, reaching 37.5% of the United States population—275 million doses—roughly a year and a half from when the disease is thought to have first appeared in Seattle. From then to now, we identified the disease, developed a vaccine practically overnight after sequencing its genetics, then tested, manufactured, and distributed it at hundred-million-dose scale. Doing this required extraordinary effort across everything from logistics, to precision manufacturing and molecular biology.

Reflecting on this, I considered how many people, and how much specialized expertise, was brought to bear on this problem—and the nature of 21st-century wealth. We write a lot about strip malls, taco joints, and housing at Strong Towns; perhaps wise considering these are basic necessities of life (food, shelter, toothbrushes). But these things don’t yield the kind of products the United States makes uniquely well: world-leading movies and TV, electric cars, or vaccines. This is the stuff of 21st-century wealth, areas where the United States excels due to a highly educated workforce, supported by great universities, a good legal system, and functional, honest government.

What does this have to do with Strong Towns? A lot, starting with the realization that place isn’t destiny. For a long time, “wealth” was physical, land and natural resources, a point Chuck makes when discussing the troubles of resource-based towns. Today’s story is different: natural resources matter, but all the gold in the world couldn’t develop or manufacture the COVID vaccine. With investment into intangibles (brands, patents, etc.) nearing 40% of gross business investment, it’s time to stop pretending advanced manufacturing or software development only happens in coastal cities or college towns. Not only is that false, factually speaking, it’s also a hugely wasted opportunity.

To understand how we got here, let’s review some basic economics, and consider how the American economy has changed, even as our understanding of wealth and prosperity (much of which is deeply embedded in our law, culture, and practices) lags behind.

Wealth: Not Money

In casual conversation, a large bank balance might qualify a town as “wealthy.” But this misses something important: money is just the placeholder. A town that hoards cash in the bank but doesn’t have what it wants isn’t “wealthy.”

Wealth is “what we want”; money is what’s in our pockets and bank accounts, which lets us buy and trade wealth. Wealth is:

Great schools

Well-maintained playgrounds where kids can play

Shelter, such as a house, that keeps us safe and out of the elements

Clean drinking water, and pipes that bring it to our houses

The basic problem with wealth, especially the tangible kind, is that it deteriorates, a process accountants measure through depreciation. When a city builds a school or road, it is promising, if only implicitly, that it will remain functional, requiring ongoing repair and maintenance.

Wealth is produced using an economy’s productive capacity: our collective ability to make what we want, like shoes, cars, or houses. The goal of investment, whether in business or government, is to increase our productive capacity; in business this is “profit,” in government it’s revenue from taxes. (Note that a family might call a new kitchen table, or even a car, an “investment.” These things make our lives more enjoyable, and we should have them, but they aren’t “investments” in this definition.)

When things depreciate, productive capacity must be directed to repair and maintenance. If we don’t do this, our wealth will decrease, because things will break down.

Bankers and businesspeople sometimes call money “capital,” but in economics, capital is anything that expands productive capacity: tools, machines, even software. Economists sometimes call investment “capital formation,” because upgrading our machines, skills, or tools in the hope of adding productive capacity almost by definition means upgrading our capital.

Somewhat counterintuitively, Strong Towns, as well as economics and business generally, make a lot more sense when you leave money out of it. Wealth is what we want, production and trade are how we get it, and investment lets us (hopefully) produce more. The Strong Towns “obsession with basic maintenance” is how we ensure our wealth doesn’t depreciate right out from under us.

Wealth, Then and Now

It’s worth acknowledging the accelerating pace of economic change. I think the rules have changed more in the past 150 years—four generations—than since the pyramids were built, some 4,500 years ago. My grandfather would’ve been 98 this year. He died 6 years ago, insisting that companies could never move manufacturing offshore. (He loved his V-8 Cadillac and I’m sure he’d call electric vehicles “golf carts,” like many gasoline diehards.)

As far back as the Middle Ages, the big thing was land: who had it and how much. Land meant crops, which meant food, and armies. In feudalism, the “landed gentry” sat at the top of the economic order, entitled to the literal “fruits” of peasant labor. As late as the Civil War, the U.S. federal government enticed people to move with “forty acres and a mule.”

In addition to being a major form of wealth, land has long been a source of government revenues (tax) because it doesn’t move and its ownership is carefully tracked. (I don’t hear much about “property tax evasion.”) In the United States, property tax was well established by the mid-19th century; the federal income tax wasn’t on clear legal ground until passage of the 13th amendment, in 1913.

Image via Flickr.

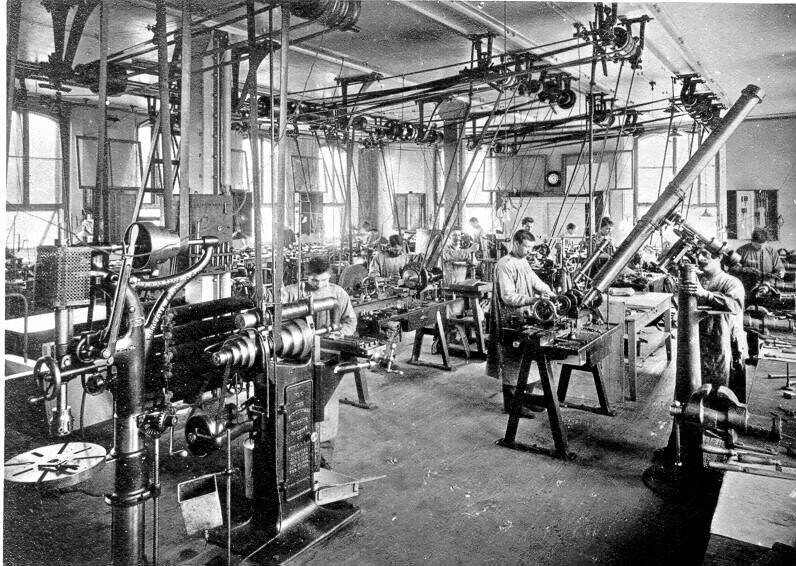

The Industrial Revolution, which started in Britain and reached the U.S. in the early 19th century (not surprisingly, the time leading up to the Civil War) was a game-changer for land. Before machines, if you wanted to produce more, there were two ways to do it: more labor (people or animals), or more land. When mechanized labor hit the scene, work could be done faster, cheaper, and better, when compared to human labor. An entire supply chain developed, and each link in the chain became fabulously rich: steelmakers, transport services (railroads), petroleum-based energy, and the banking and financial services that facilitated it.

And the value of technical knowledge increased: if you owned a machine, you needed the guy or gal that could run, repair, and operate it. The traditional professions: law, medicine, etc., had always rewarded brainpower, but it started to matter in industry, too.

A century or two later, factories and land still matter tremendously, but the march toward knowledge and know-how is accelerating, with leading regions in music, energy, finance, manufacturing, software, and consumer goods defined by their ability to convert know-how into productive economic capacity. There’s a playbook for this, and perhaps it won’t surprise anyone who’s read Richard Florida or Jane Jacobs, but it hews pretty closely to Strong Towns: embrace your strengths, reject the cult of infrastructure, create a real downtown where people want to spend time working. “Old and blighted” alongside newer and nicer.

It might be that my wife is an architect—she’s gotten to me—but I’m surprised how often I hear Strong Towns places described as “run-down,” “old,” even “neglected.” (I actually think this is the biggest long-term challenge facing strong towns: all too often, strong towns are seen as “ugly.”) But I humbly submit that, if you think “prosperity equals new,” then take a walk around Pittsburgh or San Francisco. Both are centers of scientific and creative work, and are positively blighted. I think of their buildings as paid-off Honda Civics, reliable workhorses doing what they need to, providing space to live, work, and relax, over decades. Whereas brand-new stadiums, drive-through banks, and other “infrastructure” are the leased Mercedes: it looks great, at least to some people, but the payments are absolutely killing you.

21st Century Wealth: Dos and Don’ts

Maybe you’re a resource town trying to become something different, or you just want some economic diversity—a specialty pet food manufacturer (e-commerce) or video advertising agency—to balance your community’s legacy economic base.

Forget the stadiums, roads, and other “infrastructure”; the number one advantage the United States enjoys is education, with literacy rates approaching 100% and 30% of adults having at least a bachelor’s degree. Our path to success isn’t mining or electronics assembly, but rather, invention and development of new products and services, particularly in intangible-heavy industries—things like software, cosmetics, semiconductors, or materials science.

Here are some tips on how to begin:

Do:

Image via Unsplash.

Embrace your area’s strengths. I was surprised RXBAR sold to Kellogg for $600 million (a fortune), but what surprised me less was hearing they got started near Chicago, a city that’s been doing food processing since farmers hauled it in on horse-drawn carts in the 19th century. I love hearing stories about retired auto machinists in Detroit with lathes in their basements, and was just chatting over the weekend with a guy who swears you can’t get decent clam chowder outside of New England. Play to your strengths.

Focus on walkable city centers. In addition to making an area safer, people are more likely to shop locally, and honestly, it’s just more pleasant. It doesn’t have to be the whole city, and a factory might need to locate a little farther out, but it will make the downtown area more desirable.

Make sure there are a few decent bars, lunch places, and cafés. 21st century industry is networks of small companies, not gigantic mega-firms like GM or Kellogg’s. When you spend all day in a tiny office alone, the local coffee place is your break room, client meeting site, or even a chance for some casual human interaction, after five straight hours of video calls.

Work with your landlords/property owners to cultivate a mix of building types. Focus on accommodating a range of business sizes and types. Suburban office parks aren’t good when getting started, but small companies need a place to grow when they become midsized. Ensure your city’s zoning, licensing, and approval process don’t make opening an ice cream place a $200,000 ordeal.

Don’t:

Don’t be afraid to specialize. Japan lost 1.4 million people in 2019; Zhuangzhai, a Chinese town of 100,000, supplied coffins for half of their funerals. That’s remarkable: one mid-size town, with a particular type of wood tree, supplying 740,000 coffins in a single year. Find your customers (generally on the Internet), and cater to their needs.

Don’t build “infrastructure.” Sports stadiums, office parks, “innovation districts”—just don’t. Local governments can assist by pairing local landlords and investors with business owners, helping everyone through zoning, food permitting, and other regulatory approvals, and showcasing the town through festivals and events. Keep subsidies to a minimum. If it’s worth doing, especially with interest rates as low as they are, private money will find its own way.

Don’t knock down old buildings “because they’re old.” Genuine safety hazard? Fine. But resist the urge to destroy your legacy in the name of “making it look new.” When I visit my parents, without fail, the places I end up—places like the Flossmoor Station Brewery— are the oldest, most unique spots in town.

This week is Member Week at Strong Towns. If you appreciated this content and want to see it spread, in order to help people make their places stronger and more resilient, then join the movement. Become a Strong Towns member today.

David Albrecht is CEO of Dials, the online hub for logging, planning, and publishing all things maintenance. Inspired by Strong Towns, David is also a part-time developer, and owner/operator of missing middle housing via Unchecked Capital, LLC. When not working, David and his one-year old daughter “devour” the news (The Economist and San Francisco Chronicle) in their own way: he reads it, she eats it. You can connect with David on his website and on Twitter.

Some of the best arguments for historic preservation are not aesthetic or sentimental, but economic. Here are some examples of how the preservation and reuse of historic buildings can increase an area’s productivity.