A Tale of Two Walks: Part 1

This is the first in a two-part illustrated series (see part 2 here), where I’m switching from my usual road-trip focus—such as this photo essay following U.S. Route 11 in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley or this appreciation of U.S. Route 50’s Americana landscape—to observing car-oriented places on foot. Not only do places look different when you’re a pedestrian, but things that seem like minor details, or that you might not even notice from behind a windshield, suddenly matter a lot more. And they matter the most for those who have no alternative.

For this piece, I walked Maple Avenue, the roughly one-and-a-half mile main drag of Vienna, Virginia. A relatively early and affluent suburb of Washington, D.C., Vienna was once served by both rail and trolley, a period in which it grew from a small settlement to a major suburb. A final wave of growth crested in the postwar era, when the old commercial area migrated to the more car-centric Maple Avenue, and when many of the town’s streets were built out and lined with modern houses.

In the second installment, I will be walking about three miles of Fairfax Boulevard, the stretch of U.S. Route 50 that runs through the City of Fairfax. Superficially, these are similar-looking places. Both are main local travel routes and commercial corridors alike, and both are very close to a large number of homes. These two stretches of road are only a few miles apart from each other.

The details matter a lot, and they’re not exactly the same kind of place. Maple Avenue, though always a thoroughfare and not Vienna’s original commercial corridor, resembles a street that has evolved to accommodate cars. Fairfax Boulevard, on the other hand, is a highway that has been gradually densified. As streets were opened up to cars, often gutted in the process, and highways and country roads added development parcel by parcel, they convergently evolved, as it were, into the stroad.

But not all stroads are created (or evolved) equal. Maple Avenue retains some of its old “town” DNA, while Fairfax Boulevard retains its “highway” DNA. So here, not so much in a financial or historical sense, but in a “get out of the car and experience a place“ sense, is what they feel like, what distinguishes them, and what they can learn from each other.

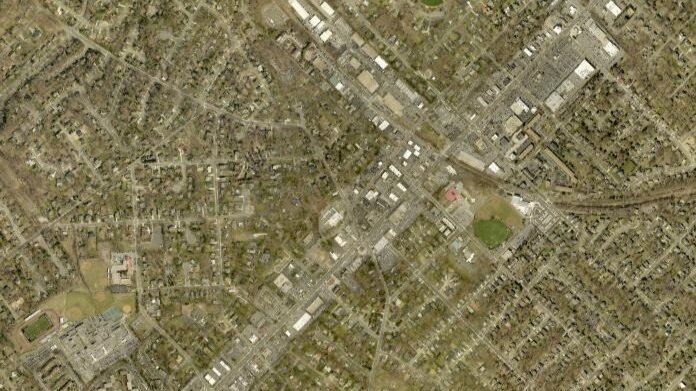

2019 aerial view of Maple Avenue corridor and surrounding homes. Image via Fairfax County Historical Imagery Viewer.

First, of course, there’s parking. As a suburbanite, I pretty much have to drive somewhere even if I’m intending to barely use my car. Vienna has on-street parking as well as a few relatively small public lots for tourists. I found a spot along an ordinary side street, between an empty lot about to undergo redevelopment and a mid-size office building. Here’s what I saw as I turned onto Maple Avenue.

View along commercial stretch of Maple Avenue right outside the town center.

It isn’t pretty. However, it isn’t quite as unpleasant to walk as it looks. This corridor has a little bit of what urbanists call “fine grain.” The individual commercial plots are relatively small and tightly built. The buildings are not set back too far, and the front parking lots are therefore narrower and less intimidating to someone on foot. Many parking spaces are also fit in between or behind buildings, or along their sides, which makes for some visual variety and makes possible those narrower front setbacks. I felt as though I could just walk into any of these stores from the sidewalk, rather than being separated from them by an ocean of asphalt. These are not traditional urban blocks, to be sure, but they give off a feeling of hugging the street.

A typical Maple Avenue strip mall, with a narrow front parking lot.

With only a single storefront facing Maple Avenue, this strip mall and its parking lot sit at 90 degrees to the main thoroughfare, minimizing the sense of gaps in the street.

There is a whisper of a streetscape here. In fact, there’s even a “true” block, created by an L-shaped strip mall whose street-facing edge has no setback at all, and has street-facing retail entrances. The scale of everything is large enough for driving to be comfortable, but small enough for walking to be comfortable. Is it a good stroad? Maybe less bad than others. It’s a space where traffic, commerce, and pedestrians can coexist reasonably well.

The placement of this strip mall makes its street-facing wing feel like an urban block.

As I reached the center of town, the concrete sidewalks turned to brick, and the strips of grass between the road and sidewalk turned to slightly elevated brick planters holding tall grass, trees, streetlamps, and occasional bushes. This improved sidewalk continues for most of the corridor.

The little planted strip might look like a bit of expensive, faux-classic cosmetic landscaping, like antique-style street lights. But on foot, it makes all the difference. For me, it provided a physical and psychological buffer from traffic. And given its elevation above the curb, it clearly marks the edge of the street for motorists as well, and has the effect of making the street feel narrower. In other words, it is a low-tech, low-cost traffic-calming device that also enhances the aesthetics and walkability of the thoroughfare.

There are also several benches along Maple Avenue, where you can sit down and watch the cars gas up or go by. There’s even a bridge over a creek where the sidewalk widens up, with a set of two benches on each side. It’s like a tiny park. As with the planted buffers, this might look like perfunctory, kitschy decoration. But it’s more than that.

Further enhancing the pedestrian experience, there are brick walls along many of the edges of strip mall parking lots, serving as a barrier between the parking lot and the sidewalk. That means that a pedestrian along much of Maple Avenue is separated from the cars in the road and in the parking lots. And these brick walls also double as little spots to sit for a moment. (I did not see any signage prohibiting sitting on them, anyway.)

Even Maple Avenue’s bus stops, marked in many places by nothing more than a sign, are both visually attractive and functional. Taken together, all of these details, relatively minor individually, add up to an environment consciously designed towards some purpose other than making driving as easy as possible. It makes a real difference in how comfortable and safe it feels to traverse the corridor on foot. It helps integrate the commercial strip with its residential surroundings. It’s also worth noting that this slower pace appears to cause no issue for emergency vehicles, an issue often raised in the context of slower or narrower streets. While I was waiting at a traffic-jammed intersection, an ambulance came up behind the red light, and the cars managed to disperse in just a few seconds.

None of this is to suggest that cars, per se, exist in a zero sum battle with pedestrians. Rather, the lesson is that making driving effortless and idiot-proof is at odds with making places that are finely textured, tightly built, and fun to explore without a car. Vienna’s relatively small, narrow parking lots, smaller setbacks, crowded intersections, prominent road-sidewalk buffers, and overall visual variety are all things which make it inconvenient to drive through when you’re in a hurry. But they’re exactly the things that make it more welcoming for local pedestrians (and for tourists, who walk around and spend money).

Another way to think of the road-versus-street dichotomy is what Shayna Goldsmith at Greater Greater Washington dubs thoroughfare-versus-destination, or through-or-too. While separation of street and road functions is ideal, it’s possible to combine them in bad and less bad ways. And that can start with tweaking spaces to be more viable and pleasant for those not in cars. Maple Avenue shows that it isn’t terribly difficult or expensive.

The same things that make for a fun afternoon in town, or that make a commercial corridor accessible via walking to nearby residents, also force motorists to slow down. Or even beckon them to stop.

Addison Del Mastro writes on urbanism and cultural history. He tweets at @ad_mastro and writes daily at Substack.

Amy Emery is a community leader focused on fostering sustainable growth and smart development in Warrenville, Illinois. She joins Norm to discuss several ways the city is working to build a core downtown. (Transcript included.)