The Galesburg Papers, Part 2: The Cure

This is part two of a two-part essay by Strong Towns member Joe Hicks about his hometown of Galesburg, Illinois. You can read part one here. All images for this piece were provided by the author, unless otherwise noted.

Downtown Galesburg, IL. (Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

What are the vital signs we’ll need to consider as we work to help Galesburg recover and thrive? We know a budget doesn’t tell us everything, so what do we use? Since it’s not a true, precise estimation, we can’t use the $20-foot-per-year number for everything. (But city staff should be able to calculate an average cost estimation like that.) What’s an easily calculated metric that tells us if we’re reaching potential financial solvency?

The primary metric we should be looking at is private investment vs. public investment. Or, in other terms, the total actual value of all the properties in Galesburg in a ratio against the value of our city’s capital assets. As mentioned before, Galesburg has a total value of $1.29 billion. We can see in this city financial document (on page 72 of the PDF) that the city has $122,621,491 in capital assets, which includes all owned land, buildings, vehicles and machines, and infrastructure. If we take a ratio of the two, we see we have a 10.5:1 ratio, or $10.50 in actual property values versus every $1 of public investment.

10.5:1 isn’t great, but it isn’t the worst. Lafayette, Louisiana, has a ratio of .5:1, or 50 cents of actual value for every dollar of public investment. They are SEVERELY underwater financially, but that doesn’t mean we are in good shape, either.

What would be a good ratio for us, one that sets us up to be able to pay our bills? The range set out by Strong Towns, the organization that inspired most of this analysis, is somewhere between $20–40 to $1. Earlier I had mentioned we would need $3.6 Billion in actual value to cover our road expenses. If we divide that by our capital assets, we get a ratio of approximately 30:1, so $30 in actual value for every dollar of public investment. So we need to grow our property values by three times to be able to be a financially healthy city.

Growing our wealth by three times—how do we go about this?

The Game Plan

We first need to invest rigorously in our downtown. We need to direct every development we can to downtown, because the rates of return for the city are higher there than anywhere else in town. Higher property values mean more money for our schools and county as well, not just our city, so all the local governments should be joining in on this.

Downtown is a place that thrives when there are more people there. People like to go where people are, so I believe we can set a positive spiral going, but we need to make Main Street specifically more of a place for people. Currently, it’s a four-lane highway that is a major road through town. It’s hard for it to be a place for people with cars zipping by, trying to make the next light. We don’t need to get rid of the cars, but we need to redesign Main Street, and all the streets downtown, to be places cars go to, and not a place cars pass through. The space needs to be designed for people first and cars last. If we’re able to make downtown a better place for people to exist, then it’ll create more demand for the area and help it become a profitable area to invest in. Our country has an extreme shortage of walkable areas, so if we can make ours one, there’s demand for it.

Our second priority needs to be encouraging small developers to do infill projects on all of our vacant lots. We do not need to open up any more land outside of town to development. If anyone wants to build outside of the 74–34 border we can’t afford to run services to them, because it won’t be profitable for the city. We already have plenty of plots of land that have sewer and street access; we don’t need to build any more. If we can fill our empty plots within town, that will get us more revenue against our current expenses without any additional infrastructure cost to the city.

Thirdly, we need to update our zoning code to not only accommodate infill projects better, but we need to be able to increase our density incrementally. Denser buildings equal higher returns on city infrastructure, which is what we need. We need ways that neighborhoods can change over time, not sit under glass like it’s in a museum because the zoning won’t allow change.

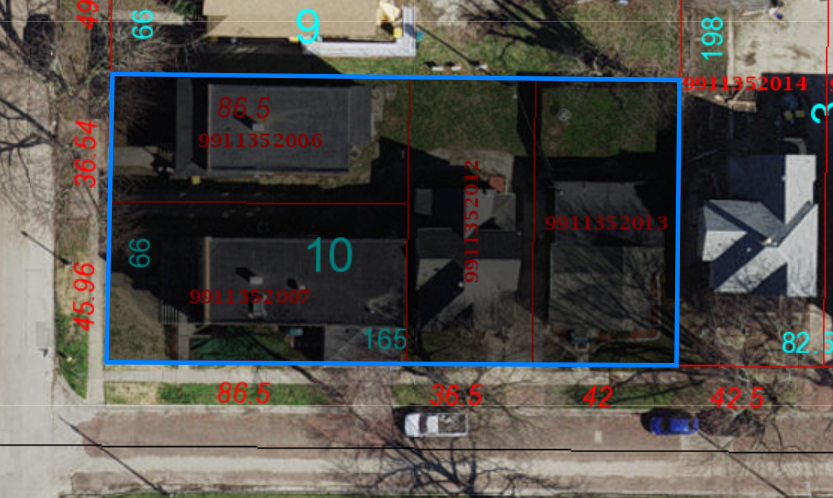

Take, for instance, this lot on Seminary, just north of downtown:

This area is 115.5 feet wide and is zoned R3A. The minimum lot width is 50 feet, so you can realistically only put two new buildings in this area. If you put two single family houses up, you’d need each house to be valued at $113,767.50 to break even on infrastructure, but that’s a bit pricey for the neighborhood. It could be two duplexes, but the units would be pretty small. But what if the minimum lot width was 30 feet? You could put up three houses that would only need to be worth $75,845 each for the city to make its money back, which is much more reasonable for the market and the neighborhood.

Look at this house:

You could build three of these 18-foot-wide houses and people would want to live in them, and they’d be profitable for the city per the infrastructure needed.

But it’s not just houses. Because of minimum lot sizes, we aren’t able to create financially productive residential areas anymore. Take a look at these duplexes on the corner of Chambers and Matthews.

These four properties are totally not compliant with the current zoning codes. The lots aren’t wide enough, the lot sizes are too small for the number of families on each lot, they don’t meet the minimum setback requirements, and don’t have the required off-street parking. These four structures couldn’t be built today. Even though they are run down, together they pay property taxes at a rate of $18,296.32 per acre! They are more productive than our Walmart, despite these buildings being in rough shape. This pattern of building is illegal today for no good reason. Are these unlivable conditions? Is there any good reason why we can’t build like this besides aesthetic preference?

Fourthly, we need to encourage small commercial developments. The building that houses Joy Garden (a downtown Chinese restaurant) pays taxes at a rate of $16,354 per acre. The building for Glory Days Barber Shop has a tax value of $40,575 per acre, and Jerry’s Barber Shop comes in at $42,621 per acre. All of these are more profitable per acre than our Walmart. We can make lots more little shops downtown like the ones mentioned above, but can’t really get any more box stores. Even if we could get more big box stores, we shouldn't want them, because the return for the city is low and the risk is high for the town, generally.

Here’s the property taxes per acre for those properties:

And since we’re here, here’s that same graph with The Kensington on it:

Galesburg Getting Better

As a general principle, we need to beef up our downtown and improve our neighborhoods. We should be obsessing about neighborhoods, doing everything we can to improve conditions around them. This creates a positive loop of seeing that the town cares about them, so the residents then care more about the town. This is a key ingredient to stopping the exodus of people out of our town.

If we can stop the flow of people leaving town and create a space where outsiders want to move in, that increases property values right there. We need to do as much as we can to make our town a more attractive place to live. The only tools for this with the limited resources we have is to voluntarily improve our properties, change zoning rules to allow for more complete walkable neighborhoods, and work with our local businesses to expand in whatever way they can.

In addition to all of that, all future developments need to be assessed on their private to public investment ratio. We need to calculate the ratio for any development that is going to need public investment. We should also look at how long it will take to repay that public investment from the taxes received. Here’s a great video with the city administrators from Fate, Texas, about how they applied this framework to go about scoring projects if you’re in the city administration.

But really, the name of the game is increasing the value of our properties versus the amount of infrastructure we have. Only then can we create a financially strong Galesburg. This piece wasn’t written with the intent to shame anyone, but to open our eyes to what the path forward is. If we take the conclusions from this analysis and others like this seriously, we can get on the path of creating a better Galesburg—one we can be proud of. I’m already proud, of course, but let’s get everyone onboard.

If you found this analysis interesting, there are a couple of talks I’d like to share:

This one is more at the 101 level, it’s Chuck Marohn from Strong Towns giving a TEDx talk on what makes a strong town.

Here’s the 202 version with Chuck again, but in a longer format.

And at a 303 level, here is a presentation from Joe Minicozzi of Urban3 about the Economics of Development for cities.

Joe Hicks writes the newsletter, Inland Nobody, which focuses on the renewal of his hometown, Galesburg, Illinois. Galesburg went through a transition during Joe's youth that shook it to its core when factories, which had been the biggest employers in the area, left town. Galesburg has since had a tough time recovering and finding a positive vision for itself. Joe left his hometown to earn bachelor degrees in economics and political science (University of Illinois at Urbana/Champaign) and returned to Galesburg to be closer to friends and family, reconnect with the community, and do "what he can to help the town be a better place." He combines his interests in economics, politics, public policy, history, and local culture to offer a new perspective on how Galesburg can move forward.

Ohio realtors and community advocates have created a practical toolkit to help communities across the state enable infill development.