Zoning Desire Paths

The 10-year-old Alaska kid deep inside me loves to go off the paths and bushwhack through the woods. But the middle-aged, obsessive-compulsive part of me cringes at the sight of children ignoring a graceful, curvy new sidewalk to walk the short way on the grass to the front door of the local pool.

Kids naturally find these informal desire paths, formed by walkers essentially voting with their feet. These improvisations may aggravate designers and landscapers and OCD dads, but they are more efficient.

My kids, on their way to the pool. (Source: Author.)

There is a famous Dwight D. Eisenhower anecdote about desire paths. As the story goes, Ike was president of Columbia University during a campus expansion. Architects couldn’t agree on the locations of sidewalks, so Ike had grass planted instead, telling the designers to watch the students for a year to see where they wore paths into the turf. Pave the sidewalks there, he told them.

An excellent story by Conor Dougherty in the New York Times two weeks ago considers how a critical mass of hundreds of thousands of people in California are cutting desire paths through the tall grass of restrictive zoning and antiquated building codes.

They are building uncodifed, informal, illegal housing in tight California housing markets and, like creative kids voting with their feet and walking the short way on the grass, homeowners are voting with their toolbelts to create zoning desire paths. And here is the news, those paths are now being “paved” by the government, to borrow Ike’s metaphor.

In Los Angeles County, home of 10 million people, there may be 200,000 informal housing units, according to an estimate from researchers at University of California, Los Angeles. Dougherty points out that is more than than the entire housing stock of Minneapolis.

The Times article quotes Vinit Mukhija, an urban planning professor at University of California, Los Angeles, who says housing built outside zoning allowances is one of the most significant sources of affordable housing in the country.

When “homes are desperately needed but also hard to build, people of every income level have decided to simply build themselves,” Dougherty writes. “The result is a vast informal housing market that accounts for millions of units nationwide, especially at the lower end.”

Over the past decade, California cities added more than three times as many people as housing units. The state is now far below the national average in housing units per capita, according to analysis from the Public Policy Institute of California. Population growth slowed and even fell in California last year, but the supply of homes is so low and the demand so great that prices only continue to rise, Dougherty writes.

Californian suburbs. (Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

So, officials in all levels of California government are paving the way for more density, following a bottom-up lead from homeowners and landlords innovating their way out of housing shortages.

California state legislators restricted local governments’ ability to block new developments and passed new laws removing regulatory barriers to building backyard homes and other accessory dwelling units (ADUs), with the hope that new construction would increase housing density in the state. The cities of Los Angeles and Long Beach have new ordinances on the books that provide a kind of amnesty for existing unpermitted units in multi-family buildings.

These changes herald a more pro-housing stance, but whether it’s enough to cover a gap estimated in the millions of units remains to be seen.

Dougherty highlights his reporting with vivid examples from the overheated Los Angeles housing market. In one, a family spent $2,000 in the mid-1990s to clandestinely convert a garage behind the main family home into a “cold but habitable unit with a bed and bathroom.” It was rented to a family friend for $300 and then to a family member for $500. The family used the money to withstand economic insecurity during the recession of the 2000s.

Ultimately, the family’s son lived there while he was getting a master’s degree in architecture. He converted it into a brand new unit of housing, made legal by recent statewide legislation that now encourages homeowners to put small rental homes on their property to help California with its chronic affordable housing shortage.

The addition is two stories tall with 1,100 square feet of living space, wrapped in a curved, fanciful exterior wall that dwarfs the ranch home out front. The garage may have become a legal residence in 2020, but it has long been someone’s home, Dougherty writes. He quotes the son: “The city rules are finally catching up to how these places are being utilized.”

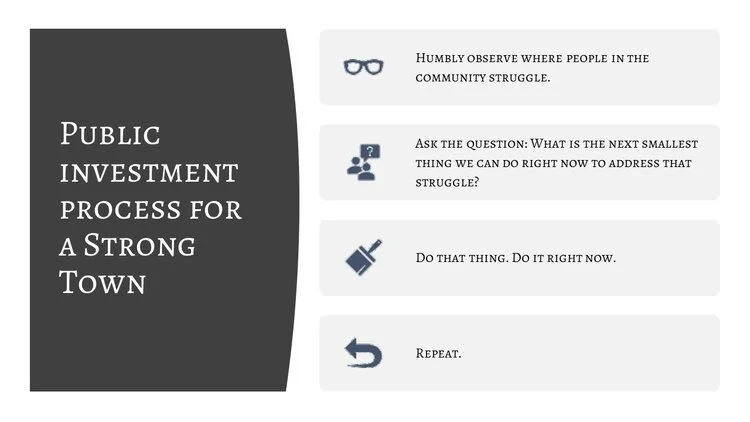

The primary starting point in the Strong Towns approach to public investment is to humbly observe where people struggle and take the first, most simple steps to ease it. The example in California is that by following the lead of its residents—paving the zoning desire paths—the government can take an important and affordable step to add housing options.

How that might translate into other jurisdictions depends on need, price inflation, level of enforcement and the kinds of built environment available for homeowners to work their creative magic to make new housing where none exists now.

Informal housing is most successful when it’s hard to see, built to escape notice from building inspectors and neighbors. That’s much harder to do in suburban Connecticut where I live, for example, than in urban Los Angeles.

The Times article quotes Jake Wegmann, a professor of urban planning at the University of Texas at Austin, who describes additions that make use of driveways and yard space instead of going up to a second or third floor, as “horizontal density.”

Wegmann tells the Times the number of tenants making use of such horizontal density easily goes into the millions nationwide. Their presence is often logged in the form of proxy complaints about city services, including parking availability on the street, sewer pipes deteriorating, and overcrowded schools. Unpermitted housing is underlying all of it, Dr. Wegmann said in the interview.

Those proxy complaints are the reasons given by suburban homeowners, state legislators, and local planning and zoning officials to argue against the addition of multi-family zoning in vigorous debates in the Connecticut General Assembly last year. Single family homes in the Land of Steady Habits commonly sit on one-acre lots, and demand for affordable housing is off the charts—aggravated by pandemic-era population shifts away from urban areas.

A new non-profit advocacy group called DesegregateCT is working to reform zoning in Connecticut, location of some of the most restrictive single family zoning in America. DesegregateCT volunteers did months of data gathering and analysis to create a Connecticut zoning “atlas” last year. It showed about 91 percent of the three million zoned acres in Connecticut can be single-family homes as of right, meaning no public hearing is necessary to build them. By comparison, only 28.5 percent of zoned lots are available for two units as of right, 2.3 percent allows for three units, and 2 percent allows for four or more. Eight towns don’t allow any multi-family housing at all.

Land use is controlled by local planning authorities in 169 separate municipalities in Connecticut, one of the reasons why DesegregateCT had to go to such lengths to analyze zoning distribution. In some cases, land use was indicated in hand-drawn maps from a pre-digital era. Advocates for reform are pushing for a statewide approach to opening up affordable housing options. It’s been slow going.

Horizontal density is unlikely to expand onto exclusive, one-acre suburban lots in Connecticut, where neighbors are very likely to notice and protest. But more urban areas accept informal units as a crucial part of their housing supply, Dougherty writes. Just how often, and how actively, city rules catch up to actual land use depends on the city and the size of the zoning enforcement and code compliance budget.

Before my family bought it as an investment, a two-family home in a streetcar suburb in Connecticut housed a multigenerational family structure. An older member of the family cut hair in the basement and slept in the partially-finished attic while the family rented out or inhabited the two formal units. This arrangement helped support a large family for a generation. No one complained to code enforcement staff. They didn’t need to.

The home we bought that had previously housed a multigenerational family structure. (Source: Author.)

Conversely, in Anchorage, Alaska, where I used to live, there were enterprising and sometimes unscrupulous homeowners who rented garden sheds with no plumbing to summer laborers for hundreds of dollars per month. People would leave plastic soft drink bottles full of urine—post-modern chamber pots—outside the sheds. Code enforcement officers were few and far between there.

One way or another, people will find a place to live or expand their offerings, despite many risks and uncertainties. State and local lawmakers would do well to get out of the way, à la California, especially when doing so doesn’t create health and safety risks.

A former code compliance officer quoted in Dougherty’s Times article is now a consultant who gives frequent talks at planning conferences. Many of the places he inspected in his 10-year career had dangerous and substandard code violations, but most did not. He tells the story of a family he cited in 2016, just as the state laws on accessory dwellings were changing.

The family patriarch had died in a bus crash in 2009 and, to supplement her income, the widow hired a neighbor to build a backyard home. It cost $16,000 to build and she was able to rent it for $500, providing years of income for her family and one unit of affordable housing in a region that badly needed it.

The officer showed up after an anonymous complaint to find a unit with plumbing and a kitchen, usable and well-maintained; but he had to write it up because it was too close to a fence. He returned to make sure it had been torn down. “(A)s a planner I had a crisis of consciousness, like ‘How many people have I made homeless?” he told the Times.

Jay Stange is an experienced community development consultant, journalist, grassroots organizer, musician, teacher, and off-grid project manager. Raised in Alaska, his passions include transforming transportation systems and making it easier to live closer to where we work, play, and do our daily rounds. Find him shopping for groceries on his cargo bike, gardening, and coaching soccer in West Hartford, Connecticut, where he lives with his family. You can connect with him on Twitter at @corvidity.