Editor's Note: The challenges our cities face are growing, but so is the strength of this movement. Every story we share, every idea we spread, and every tool we build exists because people like you are committed to showing up. Your membership isn’t passive—it’s the momentum that makes change possible.

If you want to know what it looks like to bring small-scale development back as a force that can revitalize American neighborhoods, you need to be watching South Bend, Indiana. Some of our continent’s most expensive cities are infamously innovative in finding ways to say “no” to new housing: layer upon layer of development delays, permit requirements, arcane zoning rules, appeals to mountain lion conservation, etc. Meanwhile, South Bend, a Rust Belt city that has lost 50,000 people in 50 years (mostly to its own suburbs), is busily working on finding better ways to say “yes.”

The latest innovation: an exciting new program from the city of South Bend offers pre-approved development templates to small-scale developers at no cost. The plans, developed with the help of incremental developers and design experts, are specifically crafted for South Bend’s existing neighborhoods, where they fit the current zoning rules, lot sizes and shapes, and market conditions, and nod to the city’s historic architectural vernacular. The catalog includes templates ranging from single-family houses of varying sizes and bedroom counts to a carriage house, a duplex, and a six-unit apartment building that can fit on a typical urban lot.

Imagine: While places with some of the richest existing legacies of missing-middle housing squabble internally over whether to loosen the reins on anything other than strict single-family zoning, South Bend quietly says, “Hey, want to build a sixplex here? Come on down! Let us help you.”

Context is key. South Bend has countless vacant lots, and it’s in everyone’s interest to fill them in. This includes 400 in the Near Northwest Neighborhood alone. The city’s hope is that the new catalog of plans will give would-be infill developers a jump start. If a developer uses these plans, with minor architectural variations permitted, they will avoid the need to hire an architect, and have access to speedy and simple building and development approval. The city, in return, gets a predictable form of development that is aesthetically compatible and can be replicated at scale.

South Bend’s vibrant small development community is in a good position to hit the ground running with the new program. “What I’m most excited about, quite frankly, is the duplex,” developer Mike Keen told WVPE. “And the reason for that is that in these neighborhoods, if we can make every homeowner also a landlord, now they not only have an additional income stream, but they’re providing affordable housing themselves to the neighborhood.”

This strategy—build a duplex, live in one of the units and rent out the other—has a long history as a way for those without prior wealth or connections to get into both homeownership and real estate development on the ground floor. Keen understands this well: He has been one of the foremost champions of South Bend’s incremental development community. I spoke with him at length for a 2021 piece on the remarkable growth and success of this community. South Bend is a model when it comes to making development accessible to more than the usual suspects.

South Bend Is Setting the Standard for Nurturing Small Developers

Incremental development—lot by lot, person by person—used to be the way American cities grew. If you want to know how to encourage this approach to scale back up, South Bend is one of the cities working hardest on cracking that nut.

South Bend is home to a remarkable cohort of about 100 small-scale developers. These 100 or so individuals, working separately, are collectively the largest developer in the city. Many are women and people of color, and most did not come from wealth or connections. Most of them operate in the city’s historically poor and redlined neighborhoods, and came to be developers out of a love of the community and a deep desire to see it recapture its past vitality. They are supported by not just a ton of entrepreneurial and activist energy, but also by champions within City Hall.

The city’s Build South Bend program represents an organized effort within local government, largely spearheaded by South Bend’s novel Department of Engagement and Economic Empowerment, to nurture and provide resources to this growing community. South Bend has sponsored a series of small development workshops to both introduce aspiring developers to a network of professionals who can help them with the process, as well as teach the ropes of how to select, plan, finance, and build a project that can be profitable. You can see some of the resources the city provides on the Build South Bend page, along with profiles of small-scale developers working in South Bend.

In addition, the city has worked, across departmental boundaries, to remove barriers to small-scale development, especially for those developers without prior connections or large amounts of independent wealth. A revamp of the zoning code sought to simplify unnecessary rules and make the code accessible and intelligible to anyone with “a high school education and an hour of time” to spend.

In 2021, South Bend removed its mandatory parking minimums citywide. These mandates are one of the single biggest obstacles to infill development, especially in neighborhoods that weren’t originally laid out to accommodate universal levels of car ownership. (For example, the sixplex in the city’s new catalog would likely be impossible to build on just about any lot if six or nine or 12 parking spaces had to be provided off street.)

South Bend also has a program, announced in July 2022 by Mayor James Mueller, that reimburses up to $20,000 in sewer hookup fees for infill development, another cost barrier that falls prohibitively heavily on small-scale projects versus large ones.

A “Sears Catalog” Approach for the 21st Century

This measure is not just a minor cost-cutting initiative. In some ways it harks back to how small-scale development used to work, back in the era when most development was undertaken by small businesses or individuals with local financing, not goliath corporations.

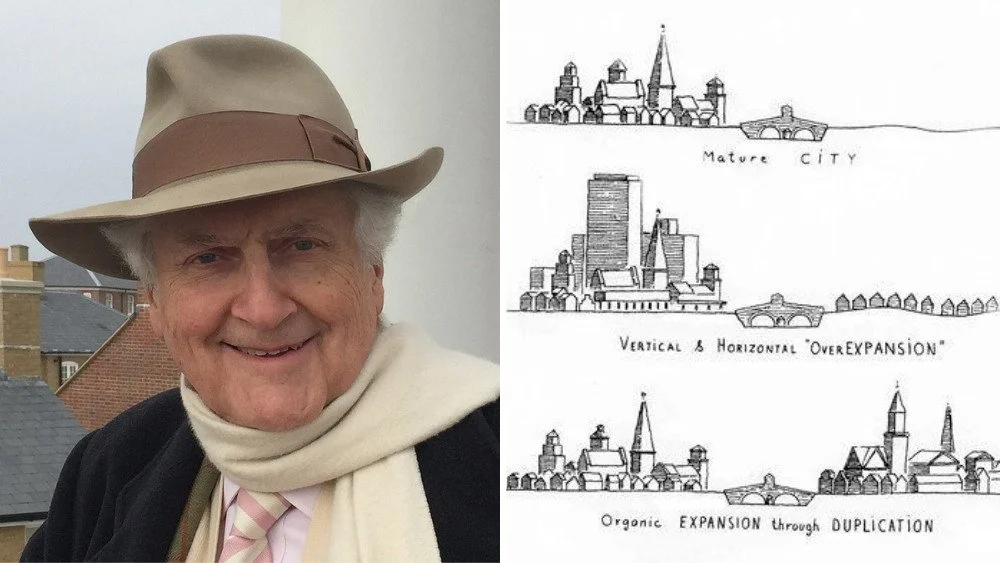

Prior to the modern era, most buildings built hewed closely to a local architectural vernacular. The way we’ve put this at Strong Towns is that people “copied what they knew worked.” This might not have been something so formal as a set of plans on paper (it likely wasn’t) in the days before building codes, although many cities did have either design guidelines or an official town architect.

In any case, home builders worked off of templates. And those templates, applied over and over at the scale of a block or neighborhood by different individuals, resulted in resilient and beautiful patterns.

The decentralization of development lasted even as mass production techniques began to simplify the process of building in vernacular styles. Urban planner and photographer Max Dubler documents the “cookie cutter” Victorian homes of San Francisco. Dubler has observed that in the late 19th century, you would build a simple “plywood box” and attach decorative moldings produced in an off-site factory, resulting in the beloved “painted lady” style that is world famous today.

In the early 20th century, the Sears Roebuck company revolutionized home building by selling immensely popular, mail-order “kit homes”—often known today as Craftsman homes—that populated burgeoning residential neighborhoods across the U.S. You would order a set of plans and the associated building materials from a catalog, and assemble the house. (Think of it as a very, very large and complicated piece of Ikea furniture.) South Bend’s website for its new pre-approved plans nods to this history with an allusion to the “Sears Catalog,” although this time, no building materials are included.

When I talk to small-scale developers today, many of them emphasize that one of the biggest things missing for them—one of the culprits in the disappearance of the small developer—is the lack of templates to make what they do more replicable. Andre Jones in Memphis, Tennessee, is one of the developers who has placed this near the top of his wish list: the ability to plug and play a tested, financially viable template for missing-middle housing in the neighborhoods where he works. “It would make it so much easier to get some of these surface lots, missing teeth in our neighborhoods built,” Jones told me in January.

“Cookie-cutter development” gets a bad rap today, because it’s associated with the standardized floor plans used by production home builders, which tend to ignore local context, climate, and are also “value engineered” to minimize construction costs at the expense of charm or detail. But this need not invalidate the idea of having templates itself—if the template is a good one.

South Bend isn’t the only city playing with this approach. A number of cities have done it specifically for accessory dwelling units, including Los Angeles. And recently, the cities of Bryan, Texas, and Claremore, Oklahoma, have adopted “pattern zones,” a back-to-the-future approach to zoning that emphasizes a consistent, simple, contextual built form over strictly regulating the use, density, and dimensions of buildings as most modern zoning codes do.

South Bend seems to be on board the cookie-cutter infill housing train. The truth is that if you want to produce a lot of really attractive cookies in a short amount of time, a cookie cutter is a fantastic tool for the job.

.webp)