What Have Cities *Actually* Accomplished in the Past 100 Years?

This article was originally published on Strong Towns member Kevin Klinkenberg’s blog, The Messy City. It is shared here with permission. All images for this piece were provided by the author.

Today we start with a very brief history of the Klinkenberg family. (Trust me, this will go somewhere.)

Klaas and Klaasina Klinkenberg (yes, you read that right), left the Netherlands in 1871 with a large family in tow. My great-great-grandfather Klaas reportedly said, “I won't have my children fight the Kaiser's wars." Smart man. Germany had just unified in 1871, and some of history's bloodiest battles were on the horizon.

The Klinkenbergs found their way to Leavenworth County, Kansas, to work some farmland. Klaas had experience as a mason and a carpenter, all of which no doubt came in handy in that era of settlement in the Great Plains. Eventually, they purchased a farm of their own in 1879, and put down roots that led to yours truly, among many others. They built a small home for themselves, and soon after some of the children similarly acquired farms and built homes.

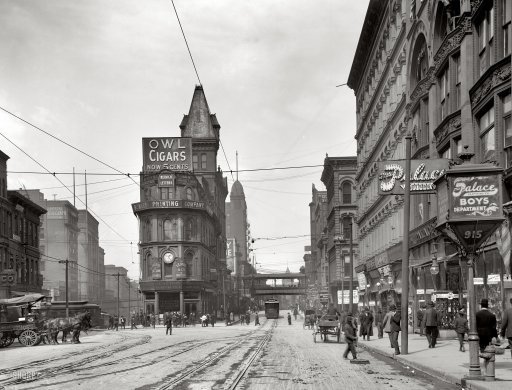

About twenty-five miles away to the east was Kansas City (KC), Missouri. The young city had a population of just over 30,000 people in 1870. Today we would call that a "small town,” though it was the largest city in the region. By the time Klaas passed away in 1889, KC had ballooned to 130,000 people. That was in just 18 years. And when Klaasina passed in 1917, it was around 300,000 people. Think about that for a moment. This particular city, in the middle of an enormous, continent-sized country, had a 10x growth spurt in the half-life of one person. There were no Autocad experts, no 3-D printing, no heavy construction equipment and no iPad apps. Technical professions were few and far between. And yet, the city grew—and kept growing.

The Klinkenberg family farmstead.

The KC population surge eventually reached almost 400,000 by 1930, when it started to level off, shortly before my parents were born. The "boom" era of KC was mirrored in many other Midwestern cities and towns. Take a look at the growth numbers for cities like Chicago, Detroit, and many more, and you can see the incredible change that happened in a short period of time. Mass immigration fueled a substantial portion of the change, with the enormous wave of people that came to the U.S. in the 1880s through the 1910s. The railroads were the facilitator of continental settlement, since they enabled a much easier movement of large numbers of people.

There's so much about that era that's fascinating to consider today, especially for those of us who find ourselves in the world of city planning, architecture, and development. One of the obvious elements is that essentially every one of the most beloved "historic" neighborhoods and buildings were built in that era. Cities that were lucky enough to have the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a boom time truly reaped the rewards of a fabulous period of architecture and design. The neighborhoods are littered with examples of what we call "missing middle" housing and commercial today. The City Beautiful movement inspired great civic architecture and beautiful parks and boulevards. In any arena of life, look at the quality of an average building from that era to one of today: schools, industrial buildings, homes, and utility structures. The built legacy is astounding.

Our cities also got wealthy, very quickly. Urban life was a relatively new phenomenon to America, which was a decidedly rural country for the first 100-plus years of its existence. That new urban wealth built much of the civic legacy that we enjoy today. And the pattern of building, in what we might call strong towns now, created very productive neighborhoods financially. Even today, we benefit from that wealth-creation. The neighborhoods in KC that were built in that era still generate six times the revenue to local taxing jurisdictions than an average neighborhood in our city. And that's after decades of decline and abandonment. So we can safely say, whatever we did in that era created generational wealth for people and for communities.

One final fascinating note is that all this was undertaken in an era of what we'd describe today as a laissez-faire approach to regulation and building. There was no Planning Commission, no Zoning Code, and effectively as free market approach as can be imagined for real estate development by those of us in 2021. The City Plan Commission in KC wasn't established until 1919 and the first zoning map and code in 1923. Essentially, the new regulations were put in place at the tail end of the boom wave. The Parks Commission was established in 1893 to oversee the Parks and Boulevards Plan, but its scope was strictly limited to that effort.

While we created a great deal of urban wealth in the boom era, there was also criticism and pushback. Some people found the new development too “chaotic” and not worthy of a rising metropolis. Others were concerned about the shanty towns that popped up around the city. So we began to see a push for more exclusive neighborhoods, more "designed" approaches to our cities and a professional management team to oversee it all.

The timing of the new "scientific" and technocratic approach to city-building is interesting, since we soon had a generation impacted by the Great Depression and World War II. Not much was built in that era, nor was much renovated. Many buildings were in fact torn down, as the new authorities and its allies in the big-business community were eager to usher in the exciting era of automobile travel. While most people probably didn't realize it much at the time, an entire new approach to building the "new modern city" had been established.

“But We Are So Much Smarter Now”

It's now well worth comparing the results of approximately 40 years of that "boom" era from 1880 to 1920, to everything that has happened over the last 100 years. We tend to accept our practices and programs today as inevitable and correct, but are they? Do our modern approaches actually produce measurably better results for people? Have we been creating beautiful places, or generational wealth? Could our centralized, managed approach to city planning handle a growth spurt like we saw in that era? Are we adding a similar diversity of housing options?

This is not to say the boom era didn't have its problems. It certainly did. A substantial portion of our population was discriminated against based on race, religion, or heritage. They weren’t able to fully participate in the rising tide of increasing wealth. We also had a lot of substandard housing. "Informal settlements," as we call them today, were fairly common. But our cities also didn't seem to have problems with "affordability" or access to opportunity. Even in the face of an effective doubling of the U.S. population through immigration, our cities managed to get wealthier, build great public amenities for people, and accommodate the new residents. And we didn't just build "housing." We built arguably the most beautiful and livable neighborhoods in the history of our country.

How is this possible? How could today's much more sophisticated people, technology, and systems be less effective at meaningful outcomes than the efforts of millions of amateurs that basically copied each other? Is this what happens when we "unleash the swarm”?

Back to my ancestors for a moment. They could effectively buy a piece of property, and do as they wished with it immediately. This was true on the farm, and If they had lived in the city itself, this was also true. There was no central authority to appeal to if someone wanted to build an apartment building next to a single-family house. Some neighborhoods could deed-restrict themselves through private agreement to only single-family houses if they so desired (and some did). And it's true that some reformers didn't like this more chaotic, messy approach to city-building. The reformers found it to be ugly, too unpredictable, and perhaps ill-fit for the new urban upper-middle class. Developers and reformers like JC Nichols in KC wrote often about what was wrong with this, and that we needed planned neighborhoods and cities. His book, The Community Builders Handbook, is the culmination of his thinking on the topic, and many of his contemporaries.

So I come back to this question: What of the actual results of our modern efforts?? We've had 100 years of increasingly-managed cities. Zoning codes and development processes just get bigger and more complicated. What is that actually doing for us?

When we face issues or challenges today, the typical responses are to take complex, siloed, and centralized systems and make them ever more complex, siloed, and centralized. Our systems tend to feed themselves, and politicians tend to enjoy creating sound-bite promises of how they can "fix" whatever ails us. And yet, we have housing issues that are spiraling out of control virtually everywhere, more neighborhoods declining than improving, a wealth gap that is widening, and environmental issues that seem daunting. A hundred years of professional management of cities has given us this, and for many the present situation seems hopeless.

We all know the definition of insanity. Why would we believe that doubling or tripling down on our current systems and approaches is the answer?

Perhaps it's past time for us to take a couple steps back, and re-examine our entire foundational belief systems as they relate to cities, development, and the management of change. It's entirely possible our professional approaches are not as wise as we think they are, nor are we any less fallible than our predecessors. Perhaps we can learn an awful lot from my great-great-grandparents' generation.

For twenty-five years, Kevin Klinkenberg has worked as an urban designer, planner, and architect. He's worked in the private, public, and non-profit sectors, and now leads Midtown KC Now as Executive Director. You can find him at www.messycity.com, @kevinklink on Twitter, and @kevinurbandesign on Instagram.