High Water Victorians, Roosevelt Corner Shops, and Hipster Legos

This article was originally published on Strong Towns member Johnny Sanphillippo’s blog, Granola Shotgun. It is shared here with permission. All images for this piece were provided by the author, unless otherwise indicated.

As happens from time to time, a reader reached out to me and suggested we meet in person. A quick Google search provided a couple of links to podcast interviews where he talked about his life. He described being a military dad and how he and his wife foster and adopt children as part of their Christian faith. I drove from San Francisco to have lunch with him in Sacramento, where he gave me a day-long walking tour of his neighborhood. He was kind, smart, and charming. I’d like to think I’ve made a valuable new friend.

To the extent anyone thinks of Sacramento these days, it’s as a company town—the company being the state government. It’s the old Bonn or Canberra or Brasilia of California. Respectable enough, but a bit dull. Downtown is sleepy, especially after office hours, but the metroplex is growing rapidly. The overwhelming majority of that growth is occurring out on the suburban periphery. While “inner city” Sacramento has a patchy reputation, a handful of older neighborhoods are getting renewed attention these days, since they offer a reasonable degree of high quality urbanism at a significantly lower price point than San Francisco or the Main Street remnants of Silicon Valley.

Our walk was centered on the parts of town that date back to the Gold Rush era. Sacramento sits at a strategic point where two great rivers, the Sacramento and the American, meet and eventually connect to San Francisco Bay. This allows seafaring ships to come and go from all around the world and for smaller river boats to then travel north, east, and south to access farmland and raw materials. Sacramento thrived as the natural exchange point and value-add nexus for industry. It’s worth pointing out that in the late 1800s, Los Angeles was a dusty, scarcely populated rural backwater with no visible prospects, while Sacramento was by far the more important and dynamic city.

One of the lesser known aspects of Sacramento’s location and history involves serious cyclical floods. The same geography that provides navigable waterways for commerce and fresh water for agriculture also delivers devastating periods of inundation. The Great Flood of 1861 submerged a 300 mile (480 km) stretch of California’s Central Valley and bankrupted the young state.

Way back in pre-history the Central Valley was actually a massive lake that filled and drained as conditions fluctuated. Scientists say these mega floods occur about every 200 years and we should expect a similar event in the not-too-distant future. The next time an atmospheric river coincides with an unusually heavy spring snowmelt from the Sierras, a whole lot of California’s interior is going to be under 10 feet (3 m) of water for a month or two. Like the next really big earthquake along the coast, this is a “when,” not an “if,” situation.

Victorian-era institutions rallied and built large public works projects, such as levees and canals, to tame the water, but these earthworks didn’t always hold. As a result, the city continued to flood from time to time—not every year, and not even every decade. But the floods came often enough for people to develop pragmatic work-arounds to accommodate them.

The response from property owners was to repurpose the existing housing stock so that the primary residents lived in the upper floors of buildings, while the ground level was rented to tenants. In a flood event, renters would carry their belongings up to the higher floors for the duration, wait for the flood waters to recede, then move back downstairs when things aired out. These are now referred to as High Water Victorians.

Construction of the late 1800s involved clay bricks and naturally rot-resistant old growth timber from nearby forests. There was effectively no insulation inside the wall cavities to soak up and hold water. Air flowed freely through these porous structures and allowed the homes to breathe after a flood. Lath and lime plaster interior walls would dry out over time and not be terribly bothered by the floods. Of course, all these qualities also made old homes drafty and terribly inefficient to heat and cool. Pick your poison.

In addition to the way previous generations built adaptively given natural forces, I’m enamored by how property was understood to be an economic tool. Homes weren’t merely a static asset meant to appreciate passively over time or convey status. They were assumed to be productive businesses. Why wouldn’t anyone want to make some extra money by renting out a portion of their home? Why wouldn’t the front yard be built out into a profitable enterprise? The older parts of Sacramento are full of Roosevelt-era corner shops and home-based businesses.

Yes, this was raw, unbridled capitalism. But it also solved problems in a straightforward manner. These neighborhoods needed grocery stores, lunch counters, churches, barbers, and “affordable housing” so local property owners simply supplied it. Very often, the front lawn was the perfect place to build such an establishment. If one small enterprise failed, as many did, something new took its place. A century ago, this was just common sense.

Was this set of arrangements perfect? Absolutely not. The culture of the time had its own non-negotiable imperatives. “Irish need not apply.” “No Negros or Chinamen.” “No Jews or Catholics.” Blah, blah, blah. But over time, society traded one set of constraints for another via exclusionary zoning. Individual properties and neighborhoods are now prevented from adapting over time, so problems just fester and multiply.

Here’s a block of modest little homes within bicycle distance of the capitol dome, each fully detached with a bit of garden front and back. Notice how these homes are about as wide as a pickup truck is long. Workers housing, whether for sale or rent, was built in response to market demand, not federal subsidies or municipal mandates. Someone made money filling a need by building the kinds of homes that society required at a price that worked. This stuff isn’t complicated. And yet these same exact homes in exactly the same location couldn’t legally be built today. They’ve been regulated out of existence. Our current rules did, in fact, solve some of the problems people were keen to fix—like filtering out “the wrong element.” But new problems emerged as a direct consequence, like people living in vans or tents under the freeway.

This cottage court was built in the 1920s in what is sometimes referred to as the “Disney” storybook style. It’s kitschy and overly romantic, but people do tend to love it. The same plot of land that would otherwise hold a single-family home with a front lawn and back garden can equally accommodate a half-dozen perfectly respectable little homes for rent or sale. If the goal is to provide decent homes for people at different price points, this is a great option. But if the goal is to intentionally exclude people of lesser means (which is almost always at the heart of zoning regulations), this is completely unacceptable. Ironically, the fact that so few properties like this exist makes these cottages command very high prices. Even market-rate “affordable housing” can be made unattainable if the larger institutional dynamics put the squeeze on things.

Sprinkled around the older parts of town are infill buildings from the middle of the twentieth century. They tend to be boxy and minimalist compared to their ornate older neighbors, and they came with the trend of removing nearby buildings to make space for surface parking lots. If the goal was to make historic districts more easily accessible for drive-in suburban visitors, they failed. The suburbs are purposely built with cars in mind and are far superior to a mediocre retrofit of the older urban fabric.

On the other hand, a chopped-up, semi-suburbanized Main Street is still pretty good on foot and can continue to function in a compromised fashion for decades. I’m actually very keen on these unadorned box buildings, because they’re so easy to renovate and repurpose compared to gooey Victorians or craftsman bungalows. If I’m trying to avoid institutional friction (always!) and want a walkable, mixed-use location, these are the better buildings for my money. The cherry on top is their durability. After a flood, the concrete blocks, bricks, and unpretentious slabs can be power-washed and aired out quickly. And their style, bare as it may be, has an earnest simplicity I can appreciate.

As we walked around each contiguous neighborhood from different eras, we observed how the building stock changed. Tucked away in what looked like single-family homes were all sorts of detached backyard cottages, garage apartments, and in-law units. They were everywhere. In the past, these kinds of ad hoc arrangements were entirely normal and completely legal.

On one particular block, there was a clear line between a 1930s neighborhood and a 1950s development. The architectural style shifted from faux Cape Cod, imitation Tudor, and mock Dutch colonial to cookie-cutter ranch homes. But notice how the 1950s homes are actually duplexes. These are the kinds of properties that were profitable for private builders to construct and affordable for ordinary families to buy or rent. Yet the suggestion that new duplexes might be built anywhere near existing neighborhoods today is the kind of heresy that brings out mobs bearing firebrands and pitchforks.

So how exactly is new housing being created in Sacramento now? There are a couple of workable models. One is to find a patch of disused industrial property that’s no longer productive and transform it into a whole new neighborhood. The cost of the acreage, upgraded infrastructure, impact fees, environmental remediation, and so on all compel the builder to squeeze as many units as possible onto the site. Otherwise, each individual home or apartment will be too expensive for the market to bear.

What most people really want is a fully-detached, single-family home at a manageable price point. But they want that home close enough to civilization to still have reasonable access to economic opportunity and culture. So they settle on so-called “handshake” buildings. You can reach out your window and shake hands with your neighbor. It’s all about compromise.

I see these residential subdivisions as a peculiar mashup of medium urban density, paired with borderline suburban iconography. It’s the idea of a house and a lawn. It’s the feeling of a walkable neighborhood. In some cases, it might achieve some version of both, but in general they’re neither. I’m not saying this is good or bad. I just don’t find them satisfying enough to want to live in these places, myself.

There’s a miniature version of this same strategy that’s a bit more appealing to me, depending on the particulars. It’s the conversion of a small plot of old commercial property that’s been infilled with a smaller row of townhomes. The important characteristic is the location where the neighbors don’t freak out and resist change. That usually means a poorly aging, downwardly mobile inner-suburban strip lined with half-dead Jiffy Lubes and abandoned McDonalds. These are the places that are ripe for Hipster reinvention. You can call that gentrification if you like, but the alternative is continued decline.

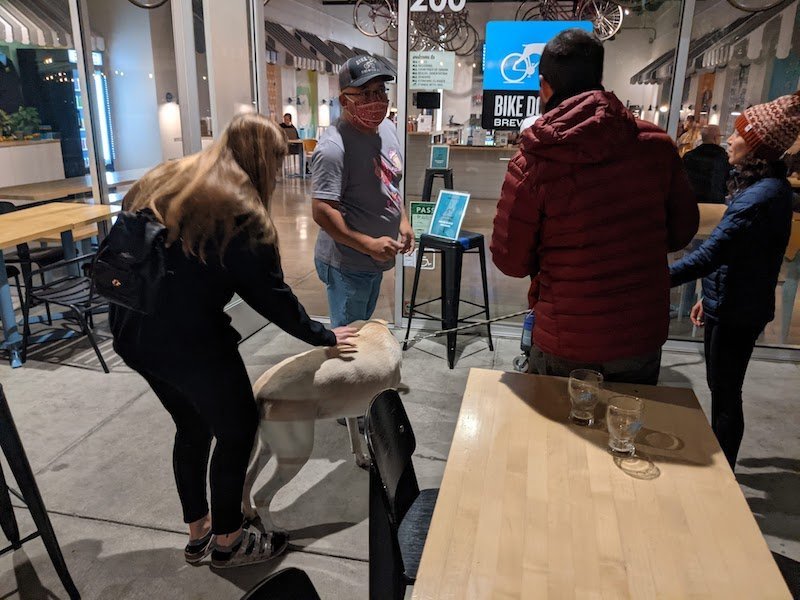

If the surrounding suburban strips are retrofitted, even a little bit, with sufficient activity close enough to walk to or ride a bike… There’s potential. A peculiar “gift” of the COVID era is the discovery that parking lots make reasonably good public plazas on the cheap. I could be tempted to think about living in one of these Lego-looking boxes under the right circumstances, even if they aren’t my first choice.

But, let’s be honest. The overwhelming bulk of new construction is being built out on the fringe of the metroplex where there’s more open space and it’s easier and cheaper to build new stuff. “Drive ‘till you qualify” has been the American housing mantra for the last three hundred years. I have no interest in this landscape, but I understand why so many people chose to migrate out to these places. Fast. Cheap. Good. Pick two… It’s all about compromise.

But here’s my primary non-aesthetic concern. Modern flood control infrastructure has effectively contained the normal seasonal events and kept the newer suburbs reasonably dry most of the time. But all infrastructure is predicated on assumed parameters. The highest flood is thought to be x feet high so the levees are built to that standard. Cost considerations and value engineering prevent overbuilding beyond a certain statistical point to keep on budget.

To me, this suggests that sooner or later, the Sacramento Delta will experience a flood that exceeds the capacity of that existing infrastructure and that old, 300-mile long temporary lake down the middle of California will return with dire consequences. Today’s new homes are made of compressed dust and synthetic materials that will turn to moldy mush pretty quickly. The 1860 census listed 380,000 people in the state. Today there are just shy of 40 million. What could go wrong?

Developers often have to jump through hoops to get their projects approved by a city. When a Costco branch in California was faced with lengthy waiting periods and public debate, it decided to take a different approach: adding 400,000 square feet of housing to its plans so it qualified for a faster regulatory process.