I (Don’t) Want More Than This Provincial Life

FADE IN on a rustic village in the French countryside. In the background, the sun is just clearing the distant hills. Somewhere a rooster crows. Otherwise, nothing is stirring. Yet. The cobblestone streets are clear for now. But the village isn’t sleeping, just standing by. Not empty, just offstage awaiting its cue.

At the house at the end of the lane, a front door opens. Out steps Belle, our hero, carrying a book. She descends the stairs toward the street…and she begins to sing:

Little town

It’s a quiet village

Every day like the one before

Little town full of little people

Waking up to say—

The village clock is chiming now. Just as the clock strikes eight, the town comes to life. Villagers throw open their windows, shopkeepers their doors. “Bonjour,” they say. “Bonjour.”

Bonjour, bonjour, bonjour.

“This Provincial Life”

This is, of course, the opening song from Beauty and the Beast—specifically, the 2017 live-action version. The 1991 original is still my favorite Disney animated film. Thirteen years old when it was released, I was outside the target demographic. But, I related to Belle. I was a book person, a daydreamer, and a romantic. I was a newcomer to Gypsum, Kansas (pop. 365). And though I loved my quiet village, I sometimes struggled to fit in.

Yet the opening song didn’t quite land for me. Belle sings, “I want much more than this provincial life.” I never did. Like Belle, I wanted adventure, but it never occurred to me I needed to leave town for “the great wide somewhere” to find it. I dreamed in fairy tales, but they weren’t set in distant forests and foreign castles; I just assumed that Gypsum Creek, and the fields of winter wheat, and the abandoned high school, were crowded with their share of fairies and gnomes and ghosts.

Later, I would hear in this song a creeping anti-rural bias. To be “provincial” literally means to be outside the capital. In Latin, a provincia was a territory under Roman domination; it was a place that had been conquered. Today we use the word provincial as a synonym for narrow-minded, unsophisticated, countrified. I never minded being countrified, any more than I minded my steak chicken fried. The description I really hated was “flyover country.” Though I’d been born in Oregon, and my extended family was all still there, and even though I proudly call myself an Oregonian again today, as a kid growing up in the Midwest I resented the implication that the people and places I loved (and found endlessly fascinating) were an afterthought on the way to someplace more interesting.

The anti-rural bias is less subtle in the live-action adaptation of Beauty and the Beast. At the end of the film, we learn that the same curse that turned the prince into a beast caused many of the castles’ other inhabitants to forget about their old life. They apparently moved to the village in a kind of amnesic haze. True love rescues the prince from spending eternity as a monster; it also rescues the courtiers from spending the rest of their days as yokels.

“Little Town Full of Little People”

CUT TO…present day. I live with my wife and daughters in Silverton, Oregon (pop. 10,484). Pre-pandemic, Silverton was becoming a bedroom community for Portland and Salem. In an age of remote work, maybe that’s less of a factor. Now we’re just a place people want to live. We have a lot going for us: a downtown with potential; walkable neighborhoods; lots of nonprofits, clubs, churches, fairs, and festivals; and proximity to good farmland, the wilderness, and the city.

During the height of the pandemic, Oregon shut down tighter and longer than most other states. With the exception of a few weeks last summer, our indoor mask mandate was in place for two years. By the end I was speculating about the psychological and social effects of not seeing strangers’ faces for so long. (I’m not saying the mask mandate was a right call or wrong one. That’s not this article. Even right calls have trade-offs.)

Yet since the mandate lifted last month, what’s struck me most has not been seeing the faces of strangers. It is seeing again—and being seen by—the friends and acquaintances who, through it all, are still quietly and reliably making our town work.

Dan “the Bread Man.” (Source: Author.)

There’s Dan at Silver Falls Bread Company. I can hear Belle sing: “There goes the baker with his tray like always / the same old bread and rolls to sell.” And I’m so glad he does. Dan the Bread Man, as we call him in our house, makes the best bread in Silverton.

A few doors down from him are Dan and Annie at Gear-Up Espresso. Their coffee shop has had to weather not only the pandemic but 18 months of road construction in front of their business. (Oh, and a Starbucks came to town.) Yet, there they are, Monday through Saturday, the hosts of what I’ve described as the community living room. When they have leftover gluten-free pastries, Dan often drops them off at our place for my housemate, who has celiac disease.

Dan of Gear-Up Espresso. Annie was out at the time this photo was taken. (Source: Author.)

There’s Jody at the grocery store, the checker you always hope to get. No mask could dim her luminous smile. On the other side of the store is George the produce clerk. Several years ago, my eldest daughter made George a comic book with him as the hero. George was Lettuce Man. My two daughters were his crime-fighting associates, Strawberry Sidekick and Blueberry Bubbles.

There’s Melissa, the newspaper reporter who walks everywhere. (She also gives our house two dozen eggs each week from a local farmer.) And John, a musician, painter, and my pastor. He walks or bikes pretty much everywhere, too.

There’s Ann A., the librarian who may also be Silverton’s most recognizable artist. And Ann H., a retiree who knows seemingly everyone in town. If something good is happening here—some new initiative or project—chances are Ann H. is near the center of it.

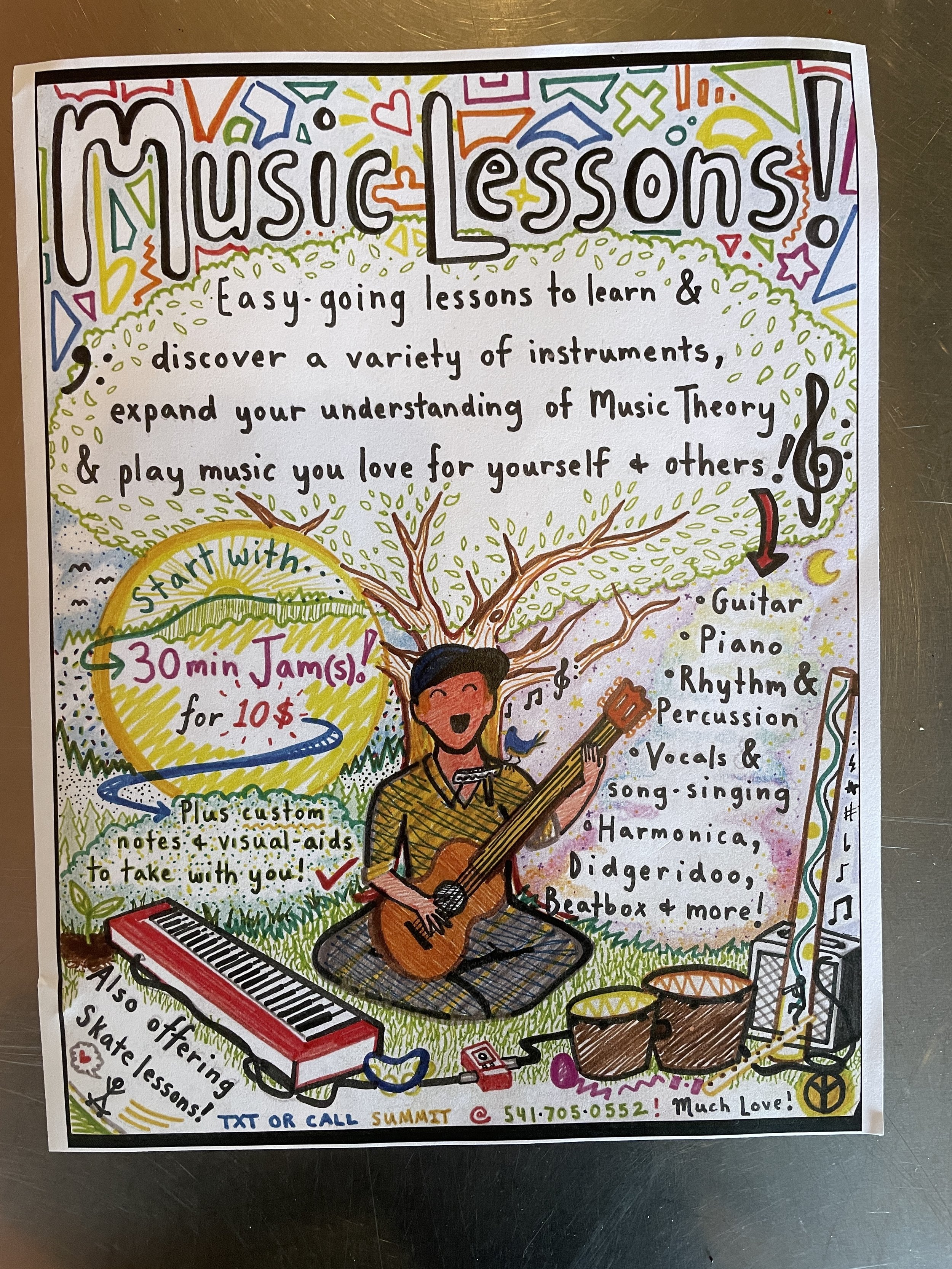

There’s Summit, a young musician and entrepreneur who can frequently be seen busking downtown. Last time I was in Gear-Up I saw some posters Summit made advertising music and skateboard lessons.

There’s young Noah and Carson, preschool teacher Meg, Johnny the barber, and Joel the chef.

There’s Gus, a local historian I think of as our town’s memory-keeper. For Gus, the streets of Silverton are alive not just with the present but with the spirit of the past.

These are just a few of the local characters I regularly see out and about. They’re not bit players in someone else’s drama. They are moving the story of our community forward. After two years, my town is saying “good morning” to itself again, and this is who we’re talking to.

“Every Day Like the One Before”

It’s easy to take for granted the benefits of “every day like the one before,” until one day is suddenly, radically different. Yet for many people, this was never even an option. The suburban development pattern makes it challenging to forge the kind of daily social and economic relationships that make possible a good life in a prospering place.

The Suburban Experiment is historically unprecedented, yet it is now the dominant approach to growth in North American communities—and not just in the suburbs, but in our cities and small towns, too. Its incentives, codes, and regulations favor a few big box stores over many local businesses and a few big developers over many small ones. It shifts investment from high-productivity neighborhoods to those of low financial productivity. It obliterates established neighborhoods with urban freeways. It prioritizes speedy car travel at the expense of safe and pleasant walking and biking. It separates uses so we are often forced to travel great distances to buy groceries, grab that cup of coffee, go to school and church, visit friends, etc.

Belle walked past dozens of neighbors on her way to return a borrowed book. Most of us have no option but to run our daily errands via solo car trips or long bus rides.

Belle longs for much more than her provincial life. Twice this month, new Strong Towns members have sent messages to us saying they are tired of living, in their own words, in a suburban development pattern “hellscape.”

Back in 2019, my friend Steve MacDouell wrote an article for Strong Towns that made the case for public spaces. We need to design for serendipity, he said. “Public spaces that are designed and programmed for serendipitous encounters keep us from becoming isolated from our neighbors—and can, over time, lead to more interconnected, resilient neighborhoods.” Daniel Herriges wrote something similar for us last year, in an article on “delight-per-acre,” a celebration of design that is “rich in sensory detail, intrigue, and serendipity.”

I’m all for celebrating serendipity, the happy chance encounters, those little bursts of pleasure that bring joy and color to life. But this article is a humble defense of the dependable. The Strong Towns approach sets the stage not only for serendipity but predictability. A strong town is one where we come to expect the unexpected; it is also neighbors we can count on right where you need them.

Maybe I’ve been too hard on Belle, who really is my favorite. A provincial life isn’t precisely what I want, either. In a 2019 interview with The New Yorker, Wendell Berry made a distinction between the “provincial” and the “parochial.”

The word parochial is from the same Latin root as the word parish, which literally means “to dwell beside.” The mark of a provincial person, Berry told The New Yorker, is that they’re always looking over their shoulder to see if someone thinks they’re provincial. In that sense, the imagination of a provincial person is limited not by their place but by their own insecurity. It also implies that being provincial isn’t limited to the provinces; the self-consciously unimpressed Portland hipster is just as likely to be provincial as the rural daydreamer. In contrast, Berry said, a parochial person is “always assured of the imaginative sufficiency of the parish. The local place.”

Silverton isn’t a village like Belle’s or like Gypsum, Kansas. But it is big enough to live life in and small enough to be known in. (In other words, it is a parish.) Silverton has its characters, its roles, its strengths, its prejudices and its problems, an imperfect past and an unknown future. My family chose Silverton 12 years ago both for these things and despite them, and we hope to be here forever. Being a Strong Towns advocate means working to make Silverton a place worth choosing for others, and a place worth staying too. That’s work I plan to continue here until, at last, I…FADE OUT.

John Pattison is the Community Builder for Strong Towns. In this role, he works with advocates in hundreds of communities as they start and lead local Strong Towns groups called Local Conversations. John is the author of two books, most recently Slow Church (IVP), which takes inspiration from Slow Food and the other Slow movements to help faith communities reimagine how they live life together in the neighborhood. He also co-hosts The Membership, a podcast inspired by the life and work of Wendell Berry, the Kentucky farmer, writer, and activist. John and his family live in Silverton, Oregon. You can connect with him on Twitter at @johnepattison.

Want to start a Local Conversation, or implement the Strong Towns approach in your community? Email John.