Main Street vs. Big Box Stores: A Western North Carolina Analysis

We all know too well the sparse downtowns that are littered throughout rural American cities. Many of them have been constructed to let a highway barrel through on the main street, big box stores stand routinely empty as businesses come and go, and in many places what was once a center for community is now a collection of parking lots.

Too often we’ve shied away from the fiscal power of our main streets and downtowns by putting more effort into chain stores and restaurants in the name of faster economic growth.

In an old Strong Towns case study concerning building strong rural communities, we told the tragic tale of two blocks of shops that once served a healthy and growing neighborhood. When the classic main street highway was put in front of the two blocks of shops the area became blighted. The local government took one of the blighted blocks and, using incentives and subsidies, tore down the local shops and replaced them with a modern fast food franchise. While on paper this was a great improvement and place of opportunity, the math didn’t lie. The remaining blighted block was worth $1.1 million per acre while the new fast food block was worth only $610,000 per acre. The improvement performed more like a downgrade.

Time and time again, data analysis has proven that economic growth is not what we reap when focusing on single-use, large buildings with large parking lots. In a discussion about building strong rural communities, Chuck Marohn notes, “Opportunity Zones were supposed to bring Wall Street capital to rural areas, but they simply inflated real estate prices without creating an equivalent rise in wages. Infrastructure investments were supposed to attract new development, but the dollar stores and franchise restaurants that showed up merely extracted wealth while stifling local entrepreneurs.”

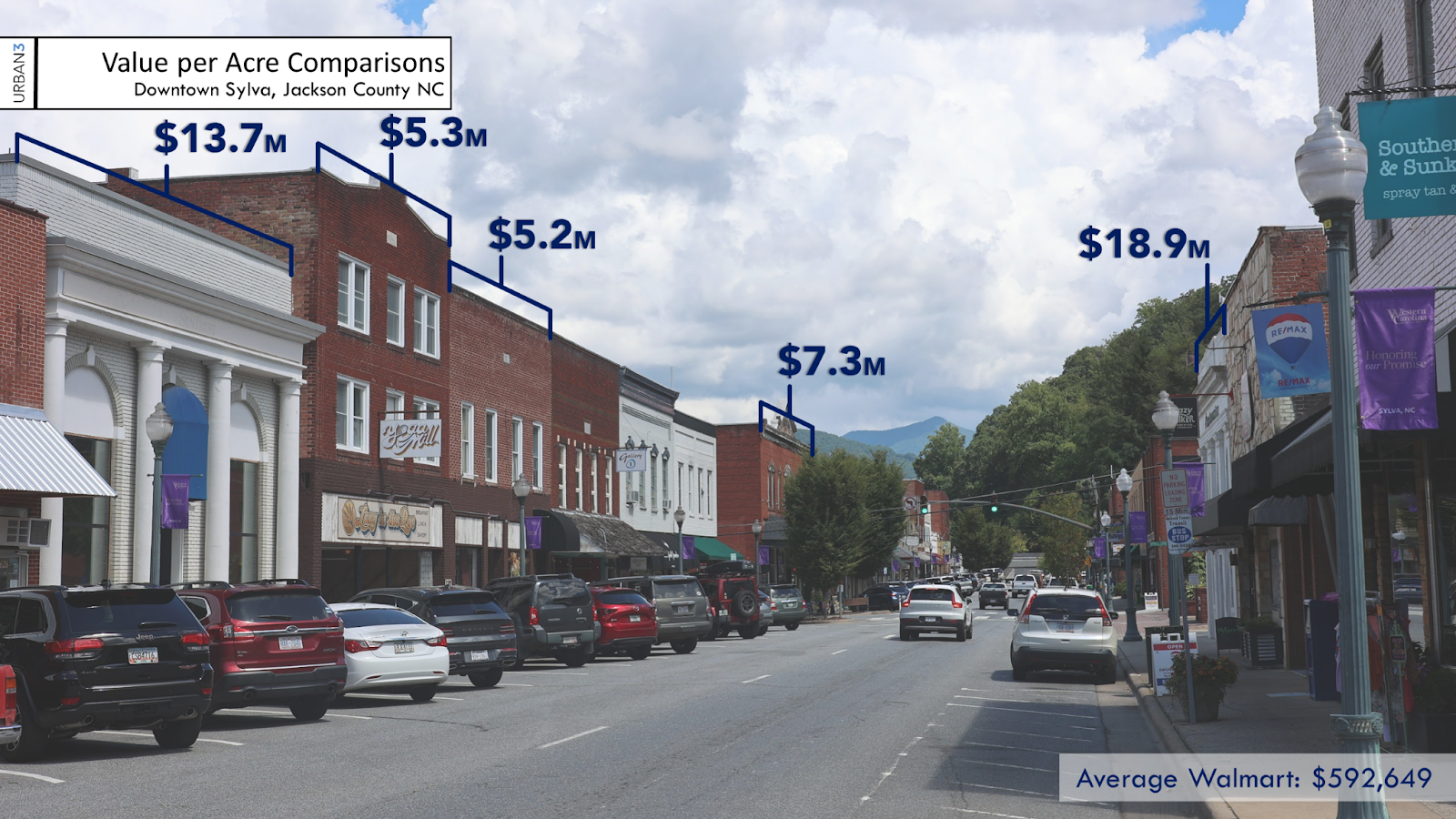

Urban3, a data analytics firm, conducted a value-per-acre analysis focused on 18 counties in Western North Carolina. Through their 3-D graphics, they show that downtown areas (even when they don’t look that glamorous) are worth much more in value per acre than suburban-style, large stores with large parking lots.

In Western North Carolina, an average Walmart is worth $592,649 per acre. A Dollar General is worth $603,647 on average, an Ingles $554,253 per acre, and McDonald’s sits at $1,078,130 average value per acre. Maybe this sounds like ideal land use at first, until you compare it to downtowns in North Carolina (pictured above) which tend to range over $5 million per acre.

A Walmart and its parking lot can easily cover a 44-acre area, taking up a large portion of potentially productive space. In Jackson County, North Carolina, Downtown Sylva hosts businesses with a value per acre worth over 10 times as much as an average Walmart.

Downtown Burnsville in Yancey County, North Carolina, hosts businesses worth millions per acre. The same goes for Downtown Murphy in Cherokee county, where the downtown area outweighs chain stores in property value by millions.

The graph below is a visual representation of the fiscal power downtowns have. Even though they rest on an acreage area not much larger than a Walmart, their value outshines the big box store tenfold. It’s apparent that even though some downtowns struggle, they have a far greater potential to build wealth within the community than large, single-use buildings.

Why are we ranting about value per acre? What does it matter if downtowns are worth more than chain stores?

Here’s one key for why examining value per acre is important (at least for Western North Carolina): it’s going to be a determinant on how much each business will be charged on their property taxes.

Property taxes represent the largest source of revenue for most local governments, so this isn’t exclusive just to North Carolina. Property taxes tend to be the primary source of funding for many public services—like public safety, parks and recreation, trash collection, libraries, etc.

Where we place our efforts in building and designing our cities is going to affect its basic functionalities in a multitude of ways, property taxes only being one. When cities are built according to the suburban development pattern, they are more expensive to maintain and lower in the amount of wealth produced per acre of land used. Additionally, “if there are disparities in property valuation,” says Ori Baber, an analyst at Urban3, “whereby high-valued properties are under-assessed, this could result in reduced property tax revenue for local governments.”

In total, 16 counties in Western North Carolina collected $689,789,066 million in property taxes (this excludes the revenue collected by other taxing districts, like incorporated cities and school/fire districts—moreover, data was unavailable for two of the counties, Cherokee and Madison Counties, in the 18-county study). These counties rely on property taxes to keep their cities functioning at a basic level. Urban3 reports that property taxes represent on average 43% of city revenue (ranging from 24% for Swain County to 53% for Transylvania County).

As we take great care in how we spend city money to build infrastructure, we should be equally thoughtful about how we are collecting those public funds.

When there are flaws in the property tax assessment system (and there are many), it has the power to constrain public wealth, consequently reducing the ability for local governments to provide core public services.

In 2021, the total taxable value of all real property in Western North Carolina totaled $123 billion dollars. Urban3 uncovered that this is only part of what Western North Carolina could be reaping, as the corrupted property tax system has shifted the burden of high property taxes from the wealthy to the poor, leaving billions of dollars untaxed.

This isn’t something that can be left unaddressed.

Urban3’s research shows that mixed-use buildings are going to increase value within a community, and that can be seen in countless traditional downtowns. We only have so much land to use, so we must encourage development and land use patterns that are productive and generate the most public wealth.

Seairra Jones serves as the Lead Story Producer for Strong Towns. In the past, she's worked as a freelance journalist and videographer for a number of different organizations. She currently resides between small-town Illinois and the rural Midwest with her husband, where they help manage a family homestead. When Seairra isn’t focusing on how to make our towns stronger, you can find her outside working on the farm, writing fictional tales in a coffee shop, or reading in a hammock.