Strong Towns Doesn’t Seem To “Fit” on a Political Spectrum. Why Is That?

Can an organization’s members spend countless hours addressing neighbors, city councils, mayors, local planning staff, and county supervisors…and then be classified as “apolitical”?

Can the same organization make transportation and housing policy recommendations at the local, state, and national levels, and then be called “non-partisan”? (A term which, taken literally, means not a part of the political spectrum.)

The answers to these questions would seem to be no. Members of the Strong Towns organization interact with citizens, politicians, and bureaucrats on a regular basis, and skillfully practice the art of politics. Yet terms like non-partisan, apolitical, politically agnostic, anti-partisan, post-partisan, and politically neutral have functioned, for years, as the family of labels by which the movement identifies itself to the wider public.

This blindly bipolar approach to the most basic terms of political engagement is not caused by some mendacious motive, nor is it the result of a failure to reason. It’s also not limited to Strong Towns or even to a mere handful of entities. Instead, this labeling predicament is the tip of a much deeper problem within our culture’s partisan discourse. It indicates structural dysfunction within political language itself.

Strong Towns is not the source of the trouble. The current linguistic quagmire had been brewing for decades before the organization was founded. It also predates the wider New Urbanist movement, as well as many other grassroots initiatives. But the nature of the Strong Towns mission does cause it to suffer from the effects of a broken national lexicon more than most organizations. And as the movement grows, these deficiencies will become significant impediments to a wider adoption of its ideas. Like it or not, it falls to Strong Towns, and perhaps to a few parallel groups, to address the disorders in our political language.

If Strong Towns could be posited as a perpetrator in the flawed use of words like apolitical, then it can be cast as a victim when it comes to more fundamental terms like left and right. Calling the organization liberal has not been welcomed by its conservative constituents. Calling it conservative puts off members with liberal values. And the other names used to describe it—libertarian, right-libertarian, free market, radical, populist, and progressive, among others—have left everyone unsatisfied.

Under the current paradigm, any attempt to place a label on Strong Towns results in a kind of koan: Can citizens from the left and right come together for a purpose that can’t be defined as left or right? Within the movement, members know they can. But within today’s partisan vocabulary, the simple marker to describe that purpose has been elusive. Like all koans, the left-right question applies universally: a growing number of organizations with purposes parallel to Strong Towns’ are unable to find concise terminology to describe their place on the political spectrum.

In an environment where labels are often wielded as weapons, many are inclined to eschew them altogether. Unfortunately, the feasibility of ignoring labels—political or otherwise—equals the feasibility of ignoring gravity. For example, imagine discussing sports without terms like forward or defensive line. Or try making sense of religions without names like Baptist, atheist, or Muslim. The absence of a one- or two-word shorthand would make every political discussion a non-starter. Just as crucially, such markers function as the entry point to deeper exploration. When engaged parties can’t get the initial simple language right, the ensuing conversation veers quickly into crosstalk.

The need for an accurate, concise, and broadly applicable description—a useful label—has lurked below the surface of the Strong Towns mission from its inception, and its absence burst back into daylight in a recent Current Affairs piece by Allison Lirish Dean as she relentlessly tagged the organization with a robust vocabulary of flawed monikers. Whatever the actual intent, Dean provided a salutary service to the movement. Her piece left no doubt that Strong Towns must craft an accurate partisan label for itself, rather than allow inaccurate ones to be pinned on it by others.

So, how do we go about repairing a disordered political lexicon?

The first step is to recognize that this is the paradigm-busting type of conundrum Albert Einstein was referring to when he said, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking that created them.” What follows is a fundamentally new way of thinking about how labels should be derived.

The most efficient path toward a short, accurate description of Strong Towns is to proceed with a series of basic assertions. The first assertion might, or might not, sound familiar: Political language is “navigational” or “locational.”

In other words, we use labels as a way of saying, “My beliefs are over here, and their beliefs are over there.” This is why allegations like far right, far left, and extremist are so effective. They provide a sense of distance between beliefs.

Sometimes, these navigational labels are asserted with great specificity, using long words everyone needs to google. More frequently, we toss around one- and two-syllable words to orient ourselves versus others.

Our spotlight will shine on the shorter words, but will focus less on the words themselves and more on how they’re ordered: “What underlying framework supports our lexicon?” For example, the high-syllable terms in the Current Affairs piece imply that political vocabulary is broad, complex, and unconnected. But a peek at the underlying framework exposes the opposite problem: political labels rely on a ridiculously simple structure.

The basic form of that structure can be unearthed through a series of short steps, beginning with the most common navigational terms: left, center, and right.

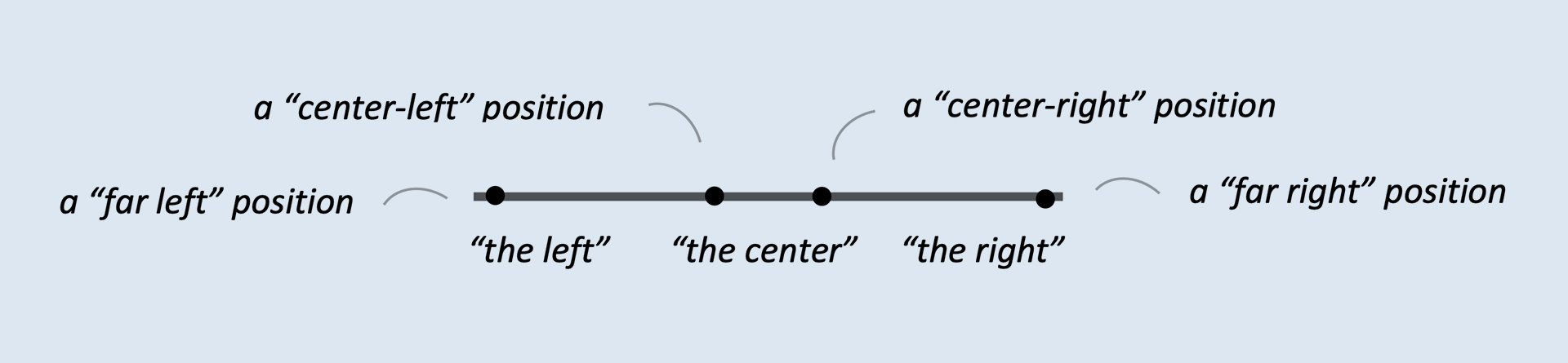

When these words are placed on a page, they spread out like links in a chain. If the terms were stacked top to bottom, or shifted to a different horizontal sequence, they would make less sense. The meanings insist on a particular order:

Geometrically, the layout of these labels forms a line segment. This indicates a purpose for the words. They describe specific “ranges” on the line.

A line, by definition, is one dimensional. When someone states a “position,” they’re actually referencing a non-dimensional point residing on this horizontal model. Terms like left, center, or right identify the position’s local neighborhood within the line.

These positions can arrange themselves along the line in a variety of distributions, depending on the public’s beliefs at a particular time. For example, one of mainstream media’s self-appointed services is to decree a partisan orientation for the entire country. This occurs frequently on election nights as they link labels to distributions through phrases like “America is center-right,” “center-left,” “fully progressive now,” or “deeply polarized.” One of those potential distributions is shown below.

After reading further, you’ll understand just how wrong such assertions can be. But for now, when you hear the term “political spectrum,” the one-dimensional line, with its attendant vocabulary and layout of points, is what is being referenced. This leads to another assertion: The term “political spectrum” always refers to a visual framework.

In turn, it leads to a principle that might seem counterintuitive to some readers, but is crucial to understanding how our lexicon functions: Political terminology is derived from the underlying visual structure.

In other words, a hierarchical relationship exists. The geometric form generates the language.

This is a cardinal insight; the most important step in breaking away from today’s dysfunctional discourse. To embrace this “visual-before-verbal” hierarchy is to cross over the inflection point between today’s broken discourse and a new, more effective way of discussing partisan conflict.

One useful function of a spectrum is that positions can be gauged with relative accuracy. And this then allows the derived vocabulary to communicate increasingly precise distinctions. In other words, labels attempt to dial in on the location of someone’s “position” on the one-dimensional segment.

Of course, purely navigational words like left, center, and right aren’t the only terms we use to describe our positions. Other terminology can transfer onto this framework as well, especially those that function as synonyms for left, center, and right.

So, the previous diagrams show, quite literally, a one-dimensional model of the political spectrum. They lead to another assertion about the labels linked to it: Today’s political lexicon is most accurately described as “one-dimensional.”

Unfortunately, we live in a multi-dimensional world, and its problems often distort the simple construct. This causes definitions of the most basic terms to stretch far beyond what a single word should be expected to mean. A related issue is that language invented to address more complex issues often has difficulty conforming to a one-dimensional framework. The diagram below shows how some of the terms from the Current Affairs piece fit easily on the line, while others struggle to identify with a particular region.

The inability of certain labels to fit on a model is an abstract concept, but its usefulness comes into view when pragmatic concerns are considered. For example, the 20th century was arguably the most bountiful period in human history, causing a sense of abundance to mute potential conflict over resource allocation. But many organizations formed in the current century advocate for a more efficient use of potentially scarce resources. Their approach generates a different genre of decision-making criteria. A one-dimensional construct can’t address this type of conflict, and therefore the new organizations find no home on it. This flaw in the underlying model explains why Current Affairs couldn’t find an accurate label for Strong Towns.

The visual framework currently serving as the basis for our political language is too primitive to address the complexity presented by many new entities. Therefore, a label for organizations like Strong Towns can only be determined after a better visual model is found.

Strong Towns and Political Conflict

Strong Towns has been engaged in various levels of political conflict since its inception. Another instance of conflict involving the organization can confirm the limitations of today’s one-dimensional model. But it will also show the way toward a better framework.

Most longtime readers will be familiar with the actions taken against Charles Marohn’s engineering license in the State of Minnesota. It pitted the Strong Towns founder against the interests of large engineering firms, allied with a state board whose members are appointed (at least in part, and indirectly) based on the firms’ recommendations.

This conflict reiterates some previously discussed limitations of the one-dimensional spectrum. For example, questions arise over which groups, if any, should be considered liberal, conservative, or centrist.

If the large engineering firms and state licensing board resided near one another as “centrists,” other questions would arise as to why a “far-left” or “far-right” Strong Towns is failing to manifest disruptive internal conflict instigated by either its conservative or its liberal members.

And, if a third scenario is posited where Strong Towns might reside near either side of the corporate/government alliance, the proximity of positions would indicate a cooperative relationship rather than an adversarial one.

The horizontal scenarios shown above are further indications that Strong Towns doesn’t fit logically on a one-dimensional model and therefore that derivative horizontal labels can’t describe it.

Fortunately, “one weird trick” can break through the confusion into a new understanding of the licensing conflict. If the line is rotated 90 degrees, a different perspective develops, along with a new set of terms to describe that perspective. By placing the parties’ positions on this vertical segment, a logical distribution of positions can be attained:

The line’s upper region can be understood through the outlook of the entities opposing Charles Marohn. They rely on top-down organizations and receive their funding from other top-down bureaucracies like Departments of Transportation. A succinct term for the power orientation of these groups is “centralized.” They stand to gain when economic and political power is concentrated.

In contrast, Strong Towns embraces a “bottom-up” approach, both organizationally, and as a problem-solving methodology. Its focus on incremental change and antifragility is consistent with the tenets of complexity theory, and its comfort with evolutionary processes is accepting of the Darwinian survival imperative. Movements like Strong Towns respect the agency of individual entities, encouraging them to combine or separate as they see fit, based on factors interpreted in real time. This approach can be described as “decentralized” or “distributed.” I often call it “citizen empowerment.”

A vertical spectrum and its labels address the distribution or concentration of power.

The vertical diagram now allows the horizontal spectrum to be viewed from a new standpoint, and its derivative lexicon can also now be assessed anew. When power connotations are removed from terms like left and right, or liberal and conservative, they can be defined with more simplicity.

A horizontal spectrum, along with its labels, addresses the values an entity chooses to favor.

In this context, “the right” holds conservative values, “the left” holds liberal (or progressive) values, and “centrists” claim to hold a balanced mix of values. The horizontal spectrum can be reassessed within this simpler approach.

The removal of power connotations allows left and right to be defined by their natural inclinations. Liberal values tend toward a focus on community, compassion, consensus, and the commons. In contrast, conservative values are oriented toward competition, commerce, competence, and, to some extent, Christianity. Both sides of this values debate respond to the conscience, or heart, and are subjective in nature as opposed to the objective, rational, head-based orientation that characterizes both sides of the power conflict.

Political “power” arranges itself along a vertical spectrum of two opposed forces: centralized and decentralized.

Political “values” arrange themselves along a horizontal spectrum of two opposed forces: liberal and conservative.

What Should Our Values Be?

In the 20th century, Americans only seriously debated one question: “What should our values be?” The answers divided along a horizontal spectrum, with liberals congregating along the left side of the line and conservatives gathering on the right.

The 21st century has seen the reemergence of a different kind of conflict, this one about power. Here, the forces of centralization congregate at the top of a vertical line while their decentralized opposition resides near the bottom.

This resurgence of the power conflict can be witnessed in a proliferation of terms that were rare before the turn of the millennium. “Elites,” “the uniparty,” “the deep state,” “one percenters” and other phrases can be applied to the top of a vertical line, but they don’t find a location on its horizontal counterpart. Similarly, Strong Towns is joined by other movements seeking to empower citizens and their communities; to claw back a renewed sense of local and personal agency. They reside at the bottom of the vertical structure and also don’t find a location on the horizontal line.

This step of comparing two partial spectrums—one addressing values and the other addressing power—explains why flawed labels have chronically been applied to the Strong Towns movement.

Labels associated with a horizontal political spectrum cannot be applied to entities that belong on a vertical spectrum. And vice versa.

In other words: Values terminology can never describe a power conflict, and vice versa.

If our exploration into political spectrums stopped here, America could be regarded as a society in which two perpendicular one-dimensional spectrums are in competition with each other, but they wouldn’t function as an effective tool for understanding the world. To find a model that allows all participants to find concise and accurate descriptions, another step is necessary.

The competing one-dimensional lines—one vertical, one horizontal—must be combined into a single two-dimensional model to become a coherent, easy-to-read framework. The most effective shape for this purpose is a circle. What were previously the top, bottom, or ends of separate lines, now become “labels” for the circle’s four poles:

This form—in which positions sit on the circle itself—allows each participant to decide whether they prioritize their values orientation over their power orientation, or vice versa. In other words, is left versus right a more important question? Or should top versus bottom be the greater emphasis?

To navigate this spectrum, it helps to separate an entity’s partisan viewpoint into three fundamental questions:

Which values do I think our society should live by? (Answers: Liberal or Conservative)

How do I think power should be allocated within our society? (Answers: Centralized or Decentralized)

Which fundamental question do I prioritize? (Answers: Values or Power)

For example, below are the three estimated responses for a political figure sometimes discussed by Strong Towns members: former Pennsylvania Governor Ed Rendell.

Values Answer: Liberal

Power Answer: Centralized

Priority: The Power Answer (significantly)

A highly incremental spectrum can represent the subtle interplay that occurs between the three responses. That interplay leads to a specific location for Rendell on the two-dimensional model:

The position of one entity can be placed on the circle, or the positions of the entire country could be placed on it (in a more realistic distribution than those shown earlier on the one-dimensional model).

Some of our answers (aka positions) will be equivocal. One person or group might favor a viewpoint midway between centralized or decentralized power, and another might hold values midway between the conservative and liberal orientations.

Other answers will be decidedly unequivocal. One individual or organization might have a definite preference for centralized power, while another might strongly favor liberal values.

For example, many participants give roughly equal weight to their answers on the first two questions. They fall into one of four categories, which reside along four regions of the circle. Notice how their labels combine terminology from the vertical and horizontal axes.

Other entities prioritize either their answer to the values question or their answer to the power question. Their positions reside close to one of the four poles.

Strong Towns sits at the bottom of the political circle. It might reside just to the left of the power axis, or just to the right. The difference isn’t material because the organization’s primary focus is on citizen and local empowerment. Another way to state the same fact is to describe Strong Towns as highly prioritizing its decentralized (aka distributed) power answer. The locations of entities engaged in conflict with it can also be displayed on the two-dimensional model. Distances between positions allow the intensity of conflict to be assessed.

The reader could rightfully question whether the positions shown above are placed in accurate locations. Perhaps they should be higher or lower, further right or left. This underscores the role of the circle as a facilitator of accurate discourse and labeling. It allows two or more parties to engage in productive dialogue regarding the position of an individual or group on the spectrum.

The circle brings us back to issues raised in the opening paragraphs of this post. The two-dimensional spectrum shown above is called the “Political Circle” because every entity on it engages in politics. It just isn’t possible for a participant to be “apolitical.”

Similarly, this structure could also be called a “Partisan Circle.” There are no non-partisans, only directions of partisanship. For example, if an entity is highly partisan in one direction, they’ll be only slightly partisan in the other. Thus, Strong Towns isn’t especially partisan regarding society’s values, but it is highly partisan regarding the distribution of power in society.

Should the partisan terminology representing Strong Towns and similar groups be called “citizen-empowering” or one of the other terms noted above? The answer follows a rule of thumb: new concepts are often developed by individuals, but language itself is crowdsourced. Certain common labels now in use, like populist or libertarian, contain flaws that will make them a poor fit. Other common labels, like grassroots or bottom-up might become functional if backed by the full faith and credit of a sophisticated geometric model. Many names could suffice, including those not yet coined, or even those currently used as pejoratives. If a proposed term’s meaning is consistent with the underlying visual structure, it can function as a useful label.

On the topic of labels, like the topic of positions, the path to resolution will feature a robust, accurate, and two-dimensional debate. Strong Towns appears to be the organization most capable of leading that discussion.

Blake Pagenkopf is a licensed architect in the states of Missouri and New York. He renovates mixed-use buildings on small town main streets. He is also the author of The Structure of Political Positions, a book about the limiting nature of America’s political language and categories. You can hear more from him in this episode of the Strong Towns Podcast.