Do Things Need To Burn for New Things To Grow?

This article was originally published, in slightly different form, on Seth Zeren’s Substack, Build the Next Right Thing. It is shared here with permission. All images for this piece were provided by the author, unless otherwise noted.

In 1906, a powerful earthquake struck San Francisco, California. The initial shock damaged buildings throughout the region. The worst was to come, however, as fires were kindled in collapsed buildings, in some cases near broken gas lines. Over the following four days, a conflagration would sweep across more than half of the city, consuming over 4.7 square miles in the heart of San Francisco, destroying 28,188 buildings, killing over 3,000 people by the official tally, and leaving between 227,000 and 300,000 people homeless (of a total population of 410,000).

San Francisco Earthquake of 1906: Ruins in vicinity of Post and Grant Avenue. Looking northeast. (Source: National Archives and Records Administration.)

It was a horrific event that has informed changes to building code and fire safety requirements to ensure it never happens again. It also serves as an illuminating natural experiment. Author, James Siodla, a professor of Economics at UC Irvine, uses the somewhat random nature of which properties burned or didn't at the edge of the destruction to look at their current land use over 100 years later. The headline conclusion is that, controlling for other factors, lots that burned are today more intensively used—bigger buildings, more homes, more commerce—than lots that did not burn. Today, the city is likely larger, wealthier, houses more people, and so forth, than if it hadn’t burned down. How could this be the case?

The paper highlights something that I’ve intuited from my work in development, but didn’t have a thorough way of thinking about. Existing buildings (that are usable) have a lot of value. The value of the building in its current use gets added to the land value if you want to buy that piece of land and build something larger. So, land with a usable building on it is worth a lot more than a similar piece of land with no building. If you’re looking to build a new building, you’re going to need a much larger and more profitable building to cover the higher land price of land with a building on it. As Siodla puts it:

“Since the durability of real estate makes it costly for developers to adapt to changing economic conditions, deficient land use patterns may emerge and persist over time… thriving cities experience a substantial barrier to redevelopment and land use changes in the form of durable capital.”

As the needs of a city change (for example, San Francisco’s crushing demand for housing and ensuing housing cost crisis), the fact that all those existing single-family homes and duplexes are quite valuable (and getting more so) is a huge barrier to redeveloping the city with a new land use pattern (six-story flats, etc.) that would be a rational response to the demand for housing. In this way, the success of a city (the value of its buildings) can actually be a big barrier to redevelopment. Builders make their income on the gap between the value of existing properties and future development. If what’s present today is valuable, it’s much less likely to get torn down to build the next increment of intensity.

Disruption and the Climax Ecosystem

Before I worked as a planner or developer, I trained as a geologist and field ecologist. One of the big lessons of wildland ecology over the last hundred years is the importance of destructive events (fires, hurricanes, etc.) in the health of natural ecosystems. We have a simple model of how ecosystems change over time, starting as grasslands, giving way to bushes, then smaller trees, then big trees, and then the “climax forest.” But we’ve learned that it’s quite a bit more complex than that, and disruption is constantly changing the forest, providing new ecological niches and opportunities. Indeed, ecosystems that are protected from regular disruption become brittle and susceptible to much larger devastation when the disruption comes. A particularly tragic example of this are the western forests of the U.S.: after decades of suppressing small fires that had historically burned off excess fuel, when fires got out of control, they burned hotter and longer. Trees that would have survived a smaller fire die in a big one, seeds that would normally emerge from the ash are baked lifeless, and so on. We have since recovered the knowledge that many pre-Columbian societies practiced their own controlled burns to promote a healthy ecology for animals and plants that provided food and other goods.

Disruption leads to regeneration. If nothing breaks, there’s little space for new things to grow. This is a painful, but hopeful lesson. Loss is necessary for new creation. And it makes sense, looking out across the history of cities: they are often burning, flooding, plagued, or razed by war…and mostly they come back, recreating themselves in new ways suited for their new challenges. Cities are complex, adaptive, evolving systems—like a forest or coral reef. Even Hiroshima, obliterated by the first atomic bomb, has grown back larger and more prosperous than before.

Hiroshima in the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing. (Source: Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Navy Public Affairs Resources.)

Hiroshima now. (Source: Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Department of State.)

Why Not Urban Renewal

In the 1950s and 1960s, planning agencies, engineers, and developers undertook perhaps the largest voluntary wholesale transformation of American cities under the name “urban renewal.” At this point, after decades of depression and global wars, American cities were tired, packed, and in rough shape. For many reasons—federally subsidized mortgages, mass car ownership, federally funded interstate highways, racially motivated white flight, and more—American cities were losing population and prosperity to new suburban communities. In the attempt to “renew” the cities, planners and engineers leveled neighborhoods to build urban highways, parking, public housing tower complexes, sports arenas, civic centers, and malls.

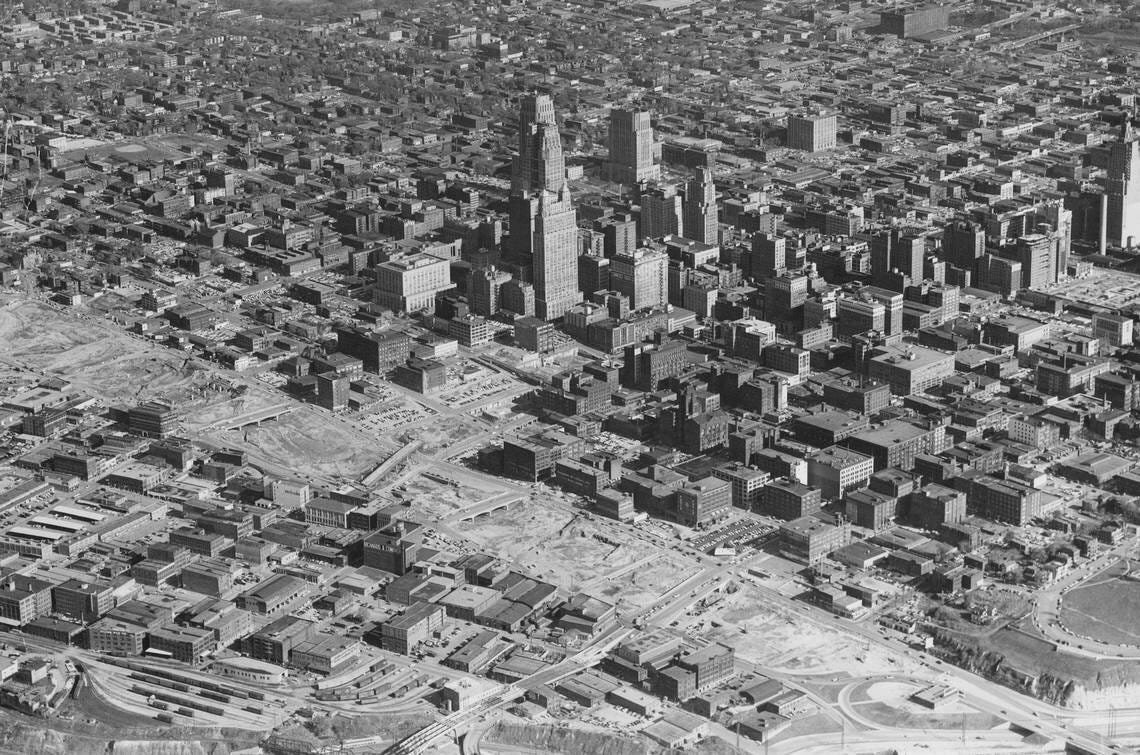

Demolition for the inner loop highway, Kansas City, 1957.

Here, we have a level of destruction not quite equal to the San Francisco fire, but certainly the slate is being wiped clean. And yet, in most cases, areas that were subjected to urban renewal were redeveloped at lower densities than before, often become blighted again, subject to cyclical public investment and decay, and so forth. What is it about urban renewal’s devastation that makes it different from the devastation of the San Francisco earthquake and fire?

Boston’s West End, Leonard Nimoy’s childhood home, was wiped out during urban renewal in the late 1950s. (Click to enlarge.)

Let’s look at the conditions on the ground when San Francisco rebuilt itself from the 1906 fire:

The city was experiencing an economic boom before the fire. The civic and business elite believed that the city should grow and become more prosperous.

There were no zoning regulations that controlled the intensity of redevelopment.

There was no master plan for redevelopment. At the time of the rebuilding, there was a push for reorganizing the city—creating wider streets, revising the land parcels, etc. But with the extreme demand to get on with it and rebuild, most of those grand ideas were scrapped.

Because of the history of the city, there were many small parcels of land.

These properties were held in diverse private ownership among many private individuals and companies.

Private automobiles didn’t exist, so there was no imperative to find extensive off-street parking space, nor to limit overall population out of concern over street congestion.

In contrast, during the urban renewal period:

Most cities were experiencing economic collapse as jobs and affluent residents fled to the shiny, subsidized suburbs being built across America. Civic and business elites were trying to reverse this trend. The idea was to manage decline, with a focus on eliminating the “blight” of the poorest neighborhoods with the worst quality of housing.

Zoning regulations were widely adopted and regulated the intensity of private development, often mandating strict separation of uses and suburban density.

Urban renewal plans involved top-down master plans for redevelopment.

The wholesale clearance of neighborhoods took millions of small lots and combined them into a much smaller number of megablocks.

Private ownership was transferred to cities, redevelopment agencies, or institutional developers.

Car ownership was ubiquitous and valorized. All properties were expected to private off-street parking for all users, and concerns about congestion lead to strict limits on overall density.

Put together, I think these themes emerge:

Looking at it this way, it’s easier to see that for a city to be “antifragile,” to bounce back from disaster and disruption stronger than it was before, it needs to embrace the same lessons of healthy ecological systems. San Francisco in 1906 showed what a strong town can do by letting many hands shape the city, letting creativity work its way up from the complex interactions of daily life, of putting people and hope at the center of your vision.

And when you look at the wreckage left by urban renewal around many American cities, you should understand these blighted areas as something akin to scar tissue in the urban fabric. Simply building big buildings on the super blocks that we created won’t address the range of conditions necessary for healthy regrowth. Consider splitting up big lots and selling the smaller parcels to private entrepreneurs, opening up more space for individual ideas and action—more small bets. The scar tissue of urban renewal isn’t just the lost buildings, it’s the whole ecology that supported those buildings.

When an ecosystem is devastated, whether by natural disaster or human greed or carelessness, we won’t get the climax forest back. It will start back at the beginning of the succession, building up the plants, soil fertility, animal community, and so forth. A healthy, rich, diverse ecosystem can come back, but it takes time. I hope that now, two generations after urban renewal, we can get serious about planting weeds and shrubs back in the scars of our cities and slowly rebuild. And if we get it right…the good news of the San Francisco fire is that we can make our cities even better than before.

Many cities are experiencing a rapid decline in their under-age-5 population, as a lack of family-sized housing forces families to leave for the suburbs. How should cities respond? One method is adopting courtyard blocks.