The Goldilocks and the Three Bears Approach to Redevelopment

As an urban designer representing a municipal redevelopment agency, I met with a lot of developers and builders. They all asked the same question: “What can I build on x lot?” The first time I was asked this question, I did not understand exactly what they were asking. I would pull out the community plan showing colorful renderings or share the community vision. I would describe the various development incentives or how they could do multiple uses.

The art of a successful redevelopment project is understanding the regulations and the process for approval of the project. Conflicting and confusing zoning regulations are the norm and not the exception. On top of that, communities tend to adopt lengthy public approval processes through hearings with a planning commission or votes with a city council. All of this creates a complex path similar to a game of chutes and ladders. As a result, it requires a lot of capital to hire a consultant to slug through the system, or a generous subsidy for a developer to realize the project will not work. Both results are equally bad and end in the same place.

It took me about a year to understand what they were really asking. Redevelopment does not require a handout or subsidy. Redevelopment requires a clear path forward. These builders and developers wanted to know when and how to obtain a development approval so they could complete a proforma. (A proforma is a financial analysis of the costs and sources of funding associated with a project, which allows a developer to assess whether the project can make money.) This knowledge inspired me to take a completely different approach.

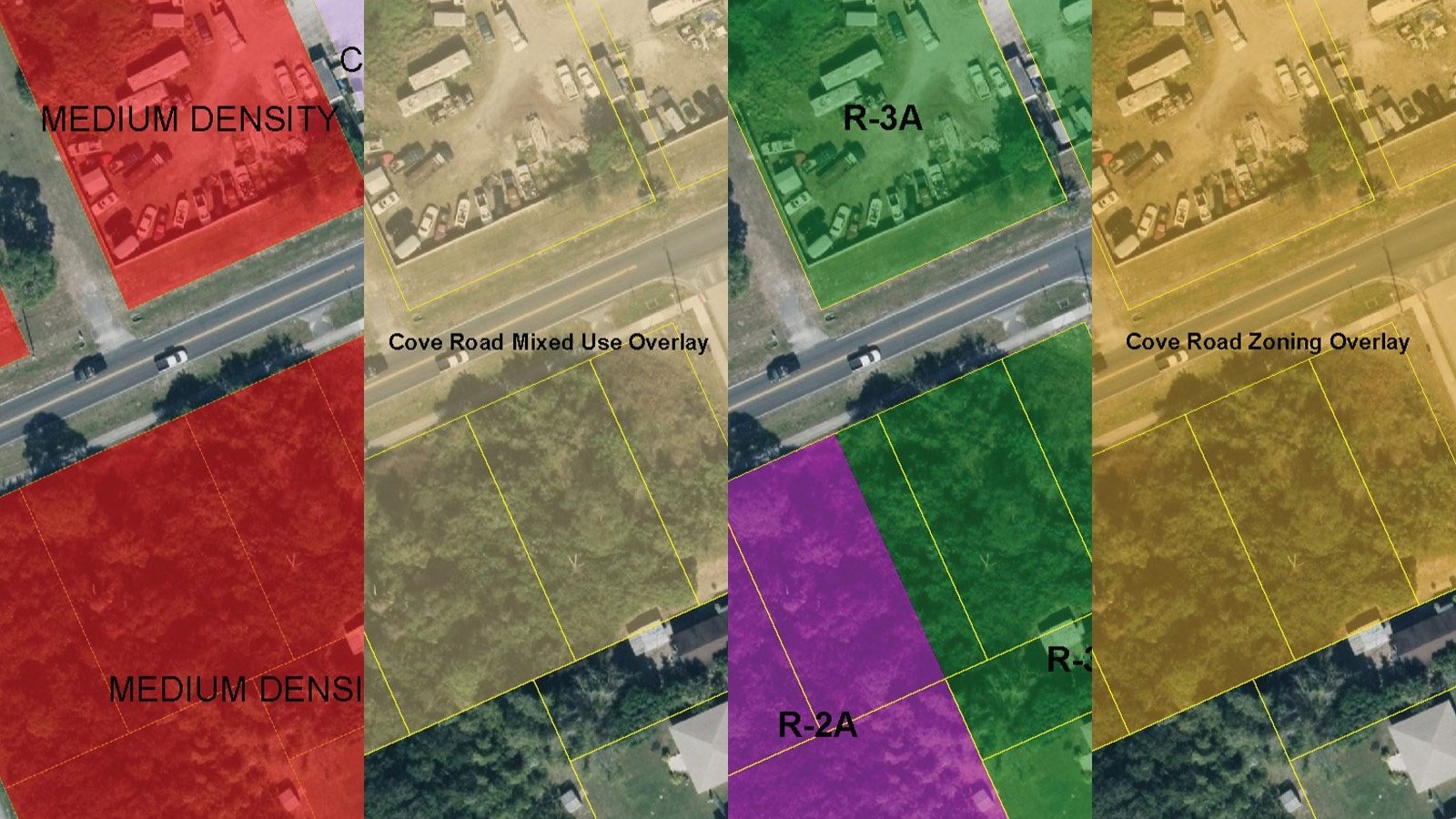

(Click to enlarge.)

The first thing I started doing was clearly identify the layers of regulations that were applicable to each site. Most codes have multiple layers of well-intentioned regulation, including zoning, special districts, and design regulations. Once this was mapped out, I met with all the department staff (meaning multiple people across multiple departments) to confirm we shared the same interpretation of these codes. This did result in lots of research, many lengthy conversations, and even shared readings of the code, to understand what applied. In this example, there were four different layers of regulations that applied: Comprehensive Plan Future Land Use, Comprehensive Plan Mixed-Use Overlay, zoning districts (this property has two), and a redevelopment overlay which superseded portions of the zoning.

Knowing is literally half the battle in the development process. As with the games of chutes and ladders, as soon as you think you are ahead, you find yourself on a chute going four steps back. Illustrating all of the regulatory layers assists everyone in understanding what is actually permitted and how the application would be processed.

(Click to enlarge.)

Once the table is set as to what you are allowed to do, I could explore how a potential project would be processed by the local government. In this example, the site had the ability to be developed as multiple houses on small lots, 3–4 small mixed use buildings, or one large mixed-use or apartment building. These three development types, respectively, increased in development potential, but also in the time required to obtain an approval. This meant that I could present a “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” approach, allowing a developer to select an option they were most comfortable with taking on.

My favorite is Option 2, which resulted in three mixed-use buildings. This middle option actually yielded the maximum number of units and maximized the development potential on this property. This option was identified when I untangled the zoning regulations, which revealed several density bonuses intended to support mixed-use development. This became my favorite because I felt I had hacked the code into a result that yielded the most benefits, while emulating the traditional development patterns in the community.

These resulting options are something that could be translated into developer’s language: an actual proforma. Developers, like any smart business people, are working to reduce risk, so the most valuable asset for a redevelopment project is not a monetary subsidy, but a reduction in the project risk. This work resulted in a higher number of development applications and permits in these redevelopment areas compared to other areas of the county.

Ohio realtors and community advocates have created a practical toolkit to help communities across the state enable infill development.