The Incredible Expanding and Shrinking House (a Prototype)

(Source: Marlene Druker.)

When there was no feasible way to make my partner’s former bachelor pad work for our family of four, we moved. The youngsters are now on their way out of the family house, and it is so empty that we are considering another move. What if, rather than having to move because life changed, the house instead could change?

I present to you THE architectural solution to this common problem: The Incredible Expanding and Shrinking House.

How does it work?

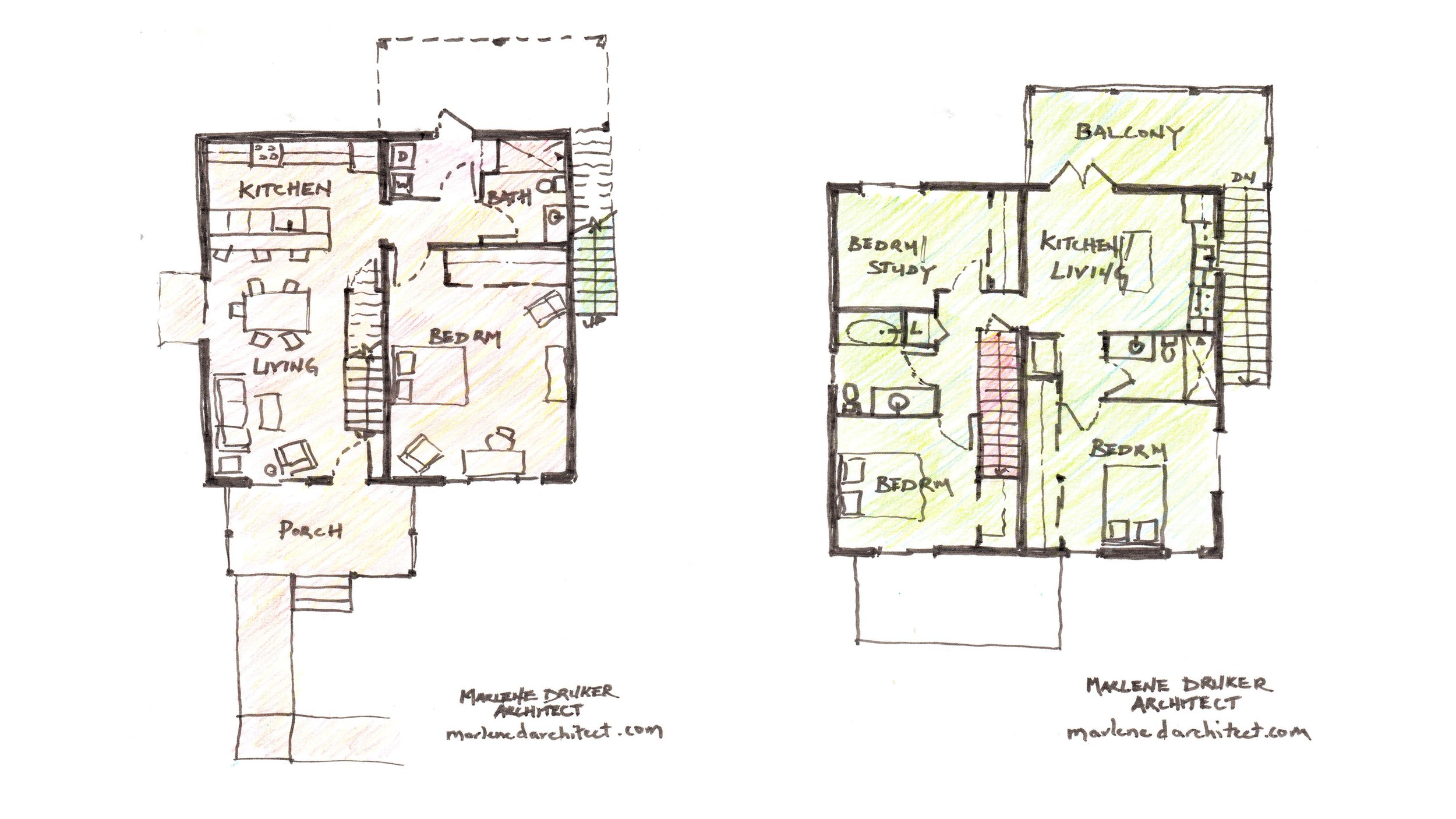

Phase one of The Incredible Expanding and Shrinking House, with the first floor on the left, and second story on the right. (Source: Marlene Druker. Click to enlarge.)

Building/Life Phase One: Building, Building Equity

Imagine yourself as a young person who has recently entered the job market and has managed to save some money. Congratulations on that and on paying your credit card bill on time every month. You can now borrow some more money with a conventional low-interest loan for home building and build this—see phase one plans above—modest two-story, wood-framed structure, which is easily divided into two units. You could start by living in the one-bedroom, one-bathroom unit above the garage, accessed by the outdoor staircase and balcony (shown in red on the phase one upper floor plan). The rest of the structure (green) has two bedrooms and two bathrooms. You can rent that out and make your mortgage payments—and still have funds left over to have a social life!

Depending on your needs, you can make the one-car garage/workshop (blue) part of the rental, or use it yourself. There is space for a stackable washer and dryer upstairs, but you may choose to save some money and have some extra storage space and share the laundry room (pink: accessible from door to exterior) with your tenants. If you are tight on funds while building, you could delay building out the lower-level bathroom and have the rental unit be just one bathroom for the time being.

Building/ Life Phase Two: Making Room

Because you had the means to have a social life, you have met someone who you want to share your life and your space with. Congratulations again! Maybe you like it cozy and will stay together in the smaller space in the house, or maybe it is now time to move into the other part of the house and rent out the smaller space. Either way, you still have some rental income coming in while you continue to build equity in the house.

Building/Life Phase Three: Here We Grow

Kids are great, even better when they have their own rooms. If you haven’t already done so, sometime around the time you add a kid to the household, you will want to move into the two-bedroom space. More kids will eventually mean taking over the entire house. The upstairs living area may be used as a home office or a playroom or converted into a fourth bedroom, if needed. If you need even more space, the garage can be converted into another bedroom, or living or office space. If there is room on the lot, you may want to add a carriage-house-type outbuilding with a garage/workshop on the lower level and maybe a space for rent or for guests or a bonus room/office above.

Phase four of The Incredible Expanding and Shrinking House, with the first floor on the left, and second story on the right. (Source: Marlene Druker. Click to enlarge.)

Building/Life Phase Four: And Away They Go

Some days, it seems to parents that kids will never grow up. But time marches on and most of them move out, sooner or later. Now the house can shrink. If you haven’t already converted the garage into a living space, you may now want to turn it into a bedroom and live on the lower level (shown in red on the phase four plan above). The bathroom on the lower level, and in fact the entire lower level, was designed from the start to accommodate people with mobility limitations—way to think ahead! It would be easy enough to add a ramp to that porch, if needed. The upper level (green) could be rented out separately as a two- or three-bedroom, two-bath unit, thereby supplementing your income. Or maybe one of those kids would like to move in there, possibly with their own little kids, so that generations can be close enough to help each other, without actually being together all the time. You might be able to work out an arrangement with people living upstairs where they do some work on the property, or even help you inside your house in exchange for reduced rent—or you could use their rent to help you pay for home or personal care needs. If you are retired and enjoy traveling, you are not leaving your entire home empty while you’re away, and that rental income can fund your wanderlust. For privacy, you will probably want to block off the top of the staircase, but if planned from the start, dividing the house in this way won’t take major renovations.

Over its lifecycle, the house has been adapted for the people in it. With the exception of converting the garage to living space, these changes are easily reversed. When it comes time to sell the house, it will appeal to people in many phases of their lives—families who need the entire house, or younger or older people who can manage with less space and would benefit from rental income.

Have I sold you yet on this modified American dream? Awesome! Please contact me and we’ll get you a set you can build off of.

But wait… Here I wish I could offer you the “you also get” part of the sales pitch, but because I am not that good a salesperson, I will discuss some of the downsides, which you may have already considered.

Many people move not because their needs have changed, but because their jobs have moved or they need to be closer to family living elsewhere. If you have picked a community and are in it for the long haul, building a home that can easily change with you will save you from having to leave when you would rather stay. I have in my work met many people who love where they live, but modifying the actual house to suit a growing or shrinking household presents many challenges. Sometimes these challenges can be overcome with very creative thinking and very healthy budgets, but sometimes it makes more financial sense for people to move rather than renovate. If you have watched the HGTV show “Love It or List It,” you have seen the reality show version of this dilemma. None of this applies to people who move because their location is far from something they need to be near.

This house is slightly smaller than average, it will only work for people who belief that less can be more. The rise of people interested in building tiny homes leads me to believe that there is a real market for “not-so-big houses.” (Thank you to architect Sarah Susanka for coining the term and for advocating powerfully for better rather than bigger.)

This house is a prototype and has no particular site. In some places, the cost of land is too high for this type of modest building. The size of the lot you will need will depend on required setbacks and how much off-street parking you feel you need or that your jurisdiction feels you need. The footprint of the prototype is 32 feet wide by 30 feet deep and the porch and balcony are each 8 feet deep. My guesstimate is that this fits very comfortably on an eighth of an acre lot that is about 50 feet wide. If your plans include wanting to build a carriage house structure sometime in the future, you will likely need a bigger lot, again depending on your required setbacks. You will also have more options for a carriage house if you are on a corner lot or if the back or one side of the lot is some sort of alley. If I were developing a series of these houses, I would plan for that when creating lots. If you are building just one of these for yourself, you should keep that in mind when evaluating lots.

This house is very simple by design. Efficiency equals value. The wall between the garage and the living space would be a bearing wall and a fire-rated wall and it would likely also be a shear wall (to resist horizontal wind or earthquake forces). The prototype isn’t very fancy, but it can be dressed up without adding unreasonable costs. Things like a tasteful palette of exterior finishes; thoughtful detailing on the porch and balcony; and possibly some small, cantilevered bump-outs and changes to the roof line would add interest to the exterior, without breaking the budget. If I were developing a neighborhood with a series of these, I would add variety with these lower-cost features.

There are some additional costs because the house is intended for more than one household. By code, you will need to add fire protection between units and you will want to add more sound proofing than in a conventional house. The kitchens don’t have to be elaborate, but having two still costs more than one. Depending on where you are in your lifecycle when you build, you may want to plan for a future kitchen by stubbing in plumbing and bringing in electricity and leave cabinets, fixtures, and appliances for later.

When housing two households, this house could be considered a duplex or it could be a house with an attached accessory dwelling unit, depending upon your jurisdiction’s definitions. If you add the carriage house and it can house another household, it may be considered a duplex or a house with a detached accessory dwelling unit, depending on how you are using it and the jurisdiction. If you are building in one of the very few places that has adopted a form-based code, as opposed to a use-based code, you are in luck: This house would look like any other, and as long as you meet setbacks and height restrictions, you could build by right. Sing Hallelujah! If you are living somewhere that has already eliminated exclusionary zoning, this is probably allowed by right. Your jurisdiction may also have some medium-density zones where this would be permitted. Researching zoning is critical before purchasing land.

Which brings me a larger issue: I wish that jurisdictions and people living in them would consider who and what their exclusionary zoning is excluding. By allowing people the flexibility to use parts of their house as rental properties, even for part of the building’s lifecycle, we enable them to build equity in our communities and to age in place comfortably. We also create a unit of housing for a household that is at a stage of life where renting makes sense for them. If the place that you live would prohibit The Incredible Expanding and Shrinking House, you should be working on changing it!

For dramatic purposes, I presented The Incredible Expanding and Shrinking House as a revolutionary innovation, but of course, it is not. People have been organically making changes to their homes, often without architects (gasp!) since people have been building houses. Many other architects have been working with similar intentions—two that I am aware of are Donald McDonald, whose work can be found in his book Democratic Architecture, and Avi Friedman, a professor at my alma matter whose “Grow Home” was built as a temporary model on the McGill University downtown campus when I was a student there, and whose explorations on these topics can be found in his many published works, including one about the Grow Home.

I introduced The Incredible Expanding and Shrinking House as THE architectural solution to the conundrum of static houses and dynamic households, but it is just one of many possibilities, which jurisdictions should be more open to, as they can improve both lives and communities.

Thanks to Fieldstead and Company for sponsoring the upcoming Strong Towns National Gathering. Learn more about Fieldstead and Company at fieldstead.com.

Marlene Druker, AIA, is a self-employed architect based in Gig Harbor, Washington. Her home office is expansive enough to house an expensive electronic drafting board and cheap trace paper, both of which were used in imagining The Incredible Expanding and Shrinking House.

Many of incremental development’s values — localism, quality and civic pride — align well with those of houses of worship. If faith communities embrace this model, we could see a wave of faith-based housing that complements the broader movement toward incremental development.