Places and Non-Places

To close out this Member Week, we wanted to share a classic post from Andrew Price, originally written back in 2014. We felt it perfectly captured the theme of this Member Week: “Look around you.”

I grew up around walking. I see cities as these magical, energetic, and complex places that are best experienced on foot. Through the eyes of a pedestrian trying to navigate a city, my perception of any place was skewed toward areas that could be reached on foot. I would gravitate toward places that had the most destinations within walking distance—from shops, to river fronts, to amenities and street life—and I viewed these centers of activity, where everything was within a few minutes’ walk, as the ultimate freedom of mobility.

Cities are collections of people, so I find it perverse when I see how much land is forbidden, unsafe, or otherwise not designed for people. Every wide road or parking lot I encounter as a pedestrian is just another obstacle, pushing the destination I am trying to get to further away. Even before I became an urbanist, I contrasted the pedestrianized shopping street in the city center, which needed no landscaping or other padding to be pleasant and enjoyable, with the rather spaced-out suburban environment.

I view everything that is not a destination (i.e., a place with a purpose) as just padding. When I encounter padding, it really takes away from the city experience. Some of this padding is necessary because it has to accommodate an environment where everyone drives. Yet, are these people driving because everything is spaced so far apart?

When you hear me talk about Places and Non-Places, I am attempting to distinguishing between the places that are destinations—where people are actually trying to get to—and the padding between them. (I was not the first to write about Places and Non-Places, by the way. That credit goes to Nathan Lewis.)

Places and Non-Places

All of the land used in cities can be divided into two categories: Places and Non-Places. Places are for people. Places are destinations. Whether it is a place to sleep, a place to shop, a place of employment, or simply a place to relax, it has a purpose and adds a destination to the city. Building interiors are the most common form of Places found in cities. Examples of outdoor Places include:

Parks and gardens.

Plazas.

Human-oriented streets.

Non-Places are the padding between destinations. Examples of Non-Places include:

Roads.

Freeways.

Parking lots.

Greenspace.

Greenspace

It is important that we make a distinction between greenspace and a park, garden, or someone's yard. If children can play out there or if you can sit down and enjoy your lunch there, then it is a Place.

If it is just mere landscaping where loitering is discouraged, then it is likely to be greenspace.

Usually a park has a name, because someone will want to go out of their way to visit it, while greenspace does not.

The main purpose of greenspace is to either prettify the area, because places like the one shown below would look pretty ugly if it were just gray pavement from the highway to the parking lot to the road.

Greenspace is also used to buffer the building from an otherwise unpleasant street. This is unnatural because if your street was pleasant, you would get the most value being located up against it—as close as possible to the center of activity.

Save your landscaping skills for parks where people can actually enjoy nature.

Place:Non-Place Ratio

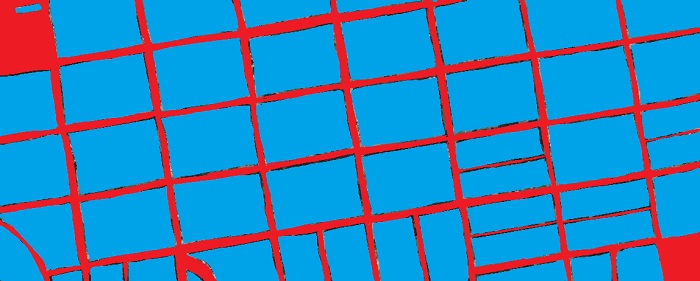

By looking at a satellite image of a city, we can get an idea of how much land is dedicated to Places and Non-Places, and we can come up with a Place:Non-Place ratio. Here is a neighborhood in San Francisco:

We can color the Places in blue and the Non-Places in red. I counted the sidewalks as Places if they were attached to a building (but not the front of a parking lot or driveway). Here is what a Place:Non-Place map of this neighborhood in San Francisco looks like:

By counting the ratio of red to blue pixels, we can come up with a Place:Non-Place ratio. The above map of San Francisco has a Place:Non-Place ratio of 406,550:95,689, or about 4.25:1 (81% place).

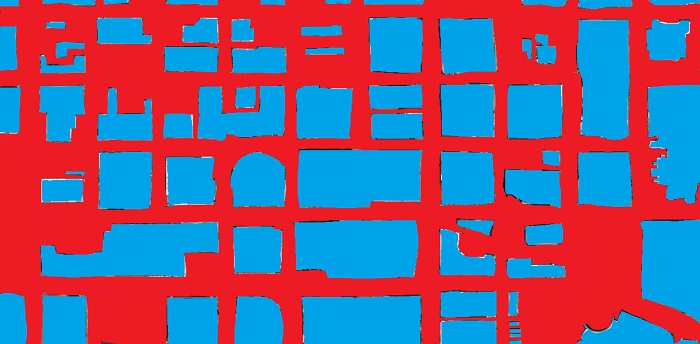

Here is downtown Phoenix:

Here are the Places and Non-Places in downtown Phoenix:

There is a Place:Non-Place ratio of 334,027:368,354, or about 0.9:1 (48% place), which indicates that slightly more land is used for Non-Places than Places.

Here is a commercial corridor in suburban Little Rock, Arkansas:

Here are the Places and Non-Places:

I came up with a Place:Non-Place ratio of 43,290:510,226, or about 0.08:1 (8.5% place), but to be fair, much of this land is underdeveloped and some of it is hard to judge, so I darkened the areas I was unsure about. The remaining bright red areas are all freeways, roads, parking lots, and greenspace:

There is a Place:Non-Place ratio of 27,370:288,178, or about 0.09:1 (9.5% place). We can see that there are very few places supporting all of that infrastructure around it. In the above example, 10.5 times more land is dedicated to Non-Places than Places! Is this a financially viable way to build a city? No.

Compare those examples and ask yourself: Which one is more more walkable? Which one is getting their money's worth out of their infrastructure?

Would it be possible to build an environment that is 100% place?

Different Types of Places

Since posting those above comparisons on my blog, I have had many people bring up that the Place:Non-Place ratio is flawed because not all Places are equal. For example, a Place that can be used by many (a public park) is better than a Place that can be used by few (a private backyard). Likewise, a multistory building adds more destinations than a single-story building.

I have had suggestions that the Place:Non-Place ratio should be scaled by the Floor:Area Ratio (FAR), population density, destination density, or some metric based on usage (e.g., if the Place is public or private, single or mixed use). This would make sense if we were using the Place:Non-Place ratio as part of a greater Walk Score calculation or something similar. But the purpose of the Place:Non-Place ratio is to point out the white elephant in the room—how much land we waste—in a way that cannot be abused (such justifying a parking lot by building a skyscraper).

Conclusion

Distinguishing between Places and Non-Places allows us to distinguish between destinations and the infrastructure and padding between destinations.

As urbanists, we often talk a lot about density. As an advocate of human-scale urbanism, before we begin considering building up, we should look at building “in.” By creating a Place:Non-Place map of our own cities, we can get a good idea of how much land is sitting underutilized. For example, here is a photo from the densest part of downtown Conway, Arkansas. It looks fully built out…

However, if we highlight the Places and Non-Places, we can see that there is plenty of underutilized land:

I calculated a Place:Non-Place ratio of 209,526:199,385, or about 1.05:1 (51.2% Place). If we fully built out the blocks with the street grid that currently exists, downtown would be closer to 75% place. That is about 23% of the densest part of town just sitting underutilized.

I encourage you to make maps like these of your own city. You can imply a lot from such a simple comparison. Some Non-Places are necessary infrastructure, but a good city planner should attempt to minimize the amount of Non-Place as much as possible. Is there something better we could have in lieu of some of those Non-Places?

As a pedestrian, Non-Places use up valuable land area, spacing out the destinations around them, potentially being obstacles that must be walked around, on land that could be used as potential destinations, themselves. As an urbanist, Non-Places use up valuable land area that could instead be used for productive, tax-generating Places. If you care about walkability or getting your money's worth out of your infrastructure, then you should care about minimizing the Non-Places in your city. Treat land as if it is the most valuable commodity your city has.

Look around you. What are the Places and Non-Places where you live—and what could your community be doing to reduce its amount of Non-Places? Join this movement of advocates who are noticing the problems in their cities and towns, and stepping up to address them. Become a Strong Towns member today.