Editor's Note: The challenges our cities face are growing, but so is the strength of this movement. Every story we share, every idea we spread, and every tool we build exists because people like you are committed to showing up. Your membership isn’t passive—it’s the momentum that makes change possible.

Houston is broke. They aren’t bankrupt or likely to file for bankruptcy any time soon. And, in reality, their fiscal problems are less immediately critical than some other major cities with large budget shortfalls. Yet, their mayor is correct when he said Houston is broke, that the financial approach of the city is clearly not working.

Houston’s situation is dire, but not in the way that is being reported. Their “staggering” $160 million deficit is just 5.8% of their total $2.77 billion budget. Compare this to Los Angeles with a projected $475 million shortfall this year; San Francisco with a projected $800 million shortfall over the next two years; Chicago, which is addressing a $538 million budget gap; and New York City, which is in a completely different place on the Richter scale with an estimated $7 billion to $10 billion shortfall.

In many ways, Houston is the cleanest shirt in the laundry basket, but it’s still a dirty shirt. Their budget is broken, their approach to finance an absolute disaster. Let’s take this acknowledgment by the mayor as an opportunity to understand exactly what is broken. It’s important because what is broken in Houston is the same thing that is broken with cities all across North America.

The budget item getting the most attention today is a recent settlement with the city’s firefighters. The city agreed to back pay for the eight years the firefighters worked without a contract, as well as raises in coming years. The city is compounding the cost by financing this settlement with a $1.1 billion bond that they have chosen to take a generation to pay off. Why amortize a short-term expense over such a long period? Because Houston is broke.

The payments on that bond amount to $40 million per year, one-fourth of their projected deficit. A child born today in Houston will make final payments on firefighter back pay from 2018 when they turn 30 years old. If that offends your moral sensibilities, you might not want to know the sausage-making that is a local government budget. Using long-term debt to cover short-term expenses is one of the most common and least offensive practices cities use to close budget gaps.

Deeply immoral, yes. Offensive? If you think so, you’d better divert your eyes.

The core of the problem is the way cities prepare their budgets, which is something we’ve talked about a lot. Cities use cash accounting, which is different from accrual accounting. To oversimplify, cash accounting ignores promises and long-term liabilities that cities make, focusing only on the amount of cash coming in and going out. When the mayor of Houston says his city is “broke,” he doesn’t mean that they have lots of future promises and lack the capacity to meet them. That has long been the case, but that’s not what he’s saying. He’s saying they are running out of cash.

Some people get upset when I use the analogy of a family budget for a city, but a city is just like a family. They can’t print their own money and all the macroeconomic theories of political economy just don’t apply to them. Cities are municipal corporations that have revenues and expenses, assets and liabilities, just like a family or a small business.

If I promise my daughter that I’m going to pay for her college, I realistically have four options. First, I can save money as she grows and have it on hand for when that large expense comes due. Second, I can borrow a lot of money when that expense comes due and then pay that debt off over time. Third, I can dramatically increase my earnings and cut my expenses to free up cash to pay the college bill. Or, fourth, I can tell her she’s on her own and walk away from that promise.

What I can’t do is not deal with it. There is no mathematical formula that allows me to not confront this promise I made, no alchemy of finance that allows me to avoid making a decision on how to address it. This is the same with a municipal corporation, aka a city government.

A developer builds a new subdivision. There are new homes and new businesses and everything is really nice. The developer builds all the infrastructure and passes those costs along to the new property owners as part of the sale. The city collects new tax revenues and hookup fees and promises to provide ongoing service and maintenance to it all.

At that moment, the local government has made an intergenerational promise to these new property owners: pay your taxes and your fees and we will provide service and maintenance. They made that promise without knowing exactly what they were promising, the amount of revenue they stood to collect, or how much that long-term promise would cost. It’s not that it’s unknowable, it’s just that cities never ask. All the city cared to know was that they would get that cash TODAY and the bulk of those promises wouldn’t come due for DECADES.

With a cash budget, that seems like a great transaction. Lots of money coming in; throw a big party. With an accrual budget, where future liabilities are recognized and accounted for when the promise is made, it’s clearly a horrible transaction. Nearly everything built in Houston over the past 75 years costs more to provide service and maintenance to than it generates in revenue for the local government. The gap becomes greater when development spreads out, with the furthest edges having the greatest negative cash flow. (See this case study of Lafayette, Louisiana, for more explanation.)

Cities use cash accounting. They have literally hit the infrastructure iceberg and don’t know it because they have not accounted for any of it. Not even asked the question. They’ll talk about pensions and firefighter settlements because that hits their cash right now—that is the thing creating immediate pain—but it is their insolvent development pattern that is grinding them down, and it won’t show up anywhere.

Cities invest in infrastructure to attract new growth and development. Stated another way, they spend public money, and take on public obligations, to attract private investment. The private investment is supposed to create the payoff that not only sustains the public investment, but pays for an improved quality of life for everyone. If that payoff is not happening, why bother?

That payoff generally does happen, in the short term, in a cash accounting system. Long term, or with accrual accounting, it’s a financial disaster. If you understand that you will understand why cities frequently do ridiculous things, often despite overwhelming opposition.

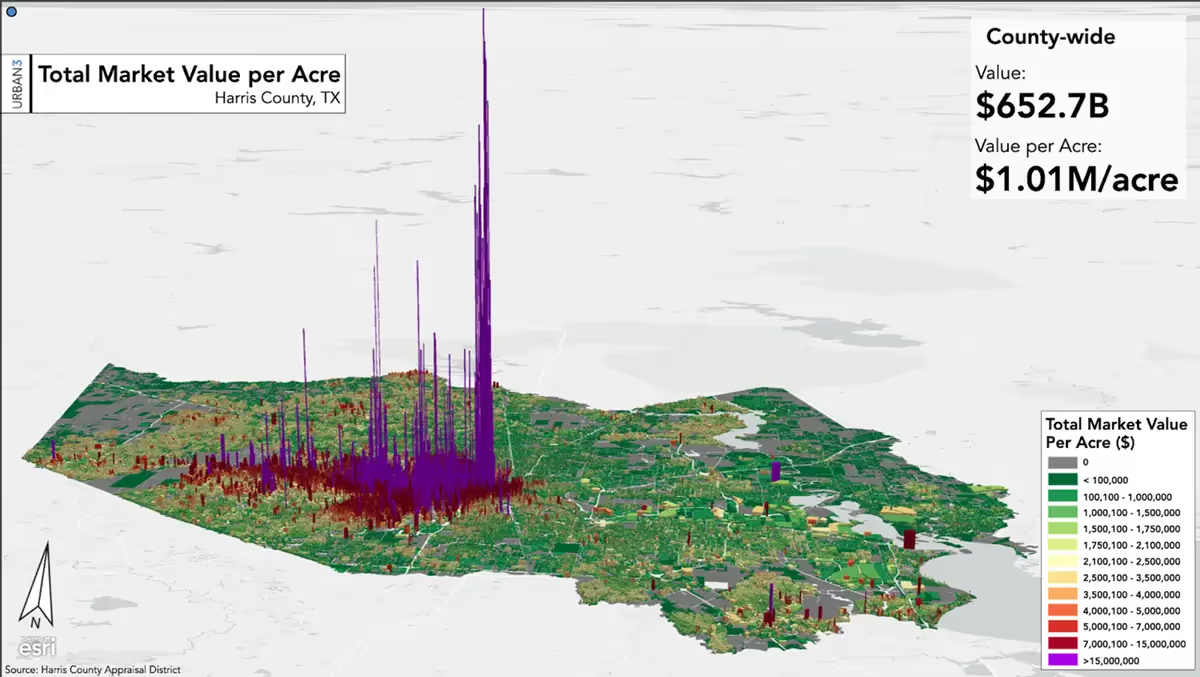

My good friend, the genius urban finance guru Joe Minicozzi and his team at Urban3, did a small survey of Harris County, including a cursory analysis of Houston. I say “cursory” because part of the brilliance of Urban3 is in finding the anomalies, the little stories that pull out the signal from the noise, and they didn’t get an opportunity to do that here (yet). Still, the first pass map of financial productivity shows a familiar pattern.

That’s the core of Houston in the middle. As with every North American city modeled by Urban3, the pre-Great Depression neighborhoods have tremendous levels of financial productivity. That is true regardless of their current level of affluence; traditional, walkable neighborhoods are financial winners wherever they are found. The pattern spreads out from the core and, as seen in other cities as well, productivity quickly dissipates.

In Houston, core neighborhoods subsidize neighborhoods built on the edge and future generations subsidize the present generation. All those liabilities have come due and, even though Houston is known for its robust growth, every Ponzi scheme eventually comes crashing down.

Houston has more than 16,000 miles of streets. That’s 37 feet of street per person, on average. I don’t know the going rate for a foot of street in Houston, but when utilities are included, it must be well into the thousands. That means that part of the wealth of each Houston resident, as collected through taxes and fees by the municipal corporation, is expected to maintain six figures worth of infrastructure. Every single person. A family of four has a generational liability of at least a half million dollars just to maintain essential infrastructure. This is not math that will ever make sense.

It’s generally believed that Detroit went bankrupt because people fled Detroit, leaving too much city to be sustained by too few people. That’s overly simplistic, but not completely wrong. If we run with it for a moment, we’ll find that Detroit has a population of 630,000 spread out over 143 square miles. That’s 4,400 people per square mile. In comparison, Houston has 2.3 million people in 671 square miles, or 3,400 people per square mile. If Detroit’s math doesn’t work—and it doesn’t—note that it has 30% more people per square mile to shoulder the financial burden of servicing and maintaining all that they have built than Houston has.

Go back to the analogy with my daughter and college. What would the fourth option look like for a city? What does it look like to walk away from a promise?

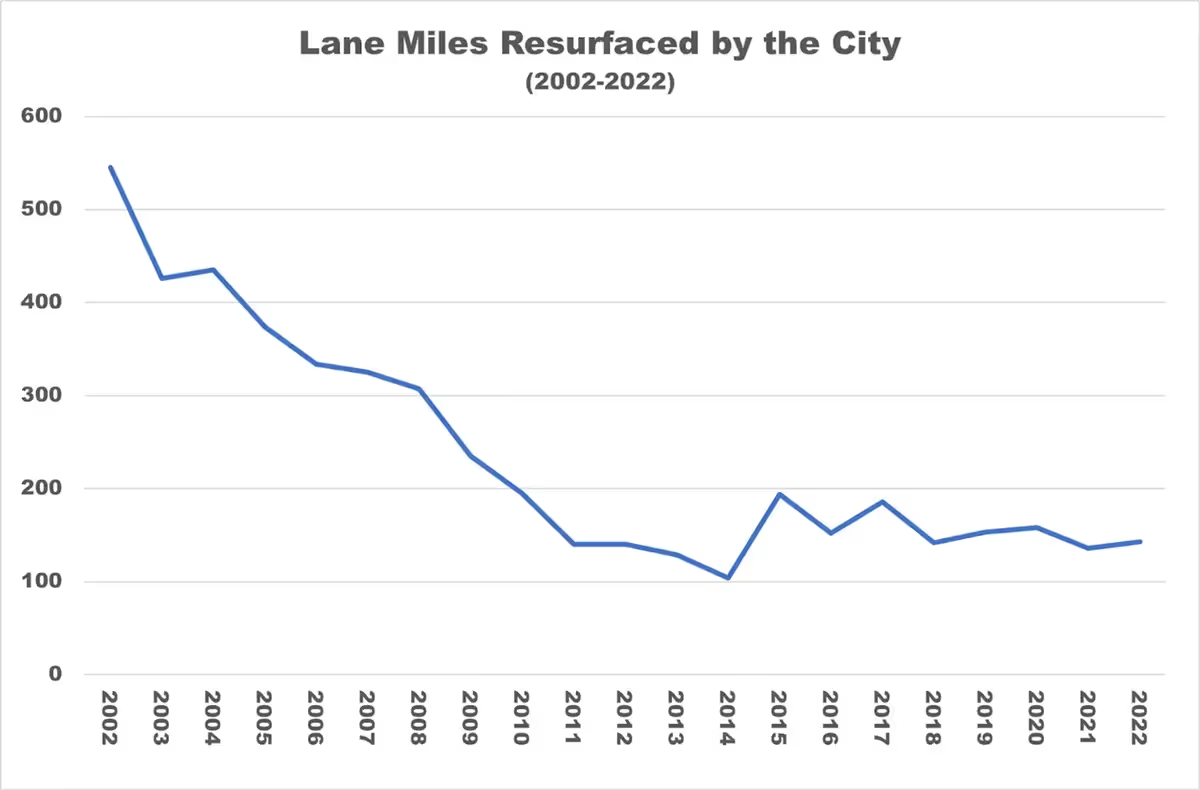

Last year, the Bill King Blog looked at Houston and why their streets are in such bad condition. The conclusion: a lack of investment. Now, the blog might have some odd reasons as to why that investment hasn’t happened, but focus on the trend. This is what it looks like when a budget gets squeezed, when debt service (aka: buying time via debt) stacks up, along with other unignorable promises like pensions and firefighter settlements. These things squeeze the budget and since streets fall apart slowly they become the thing that can be short changed without immediate pain.

The blog quotes the City’s Public Works Director back in 2016 conceding “that the City has only been doing 25-30% of the repaving necessary, but confidently predicted ‘being able to double the amount of work we do in five to eight years.’” That was naively optimistic. In reality, Houston is doing less street maintenance today than when the director made that prediction almost eight years ago.

So, Houston is financially screwed. Absolutely screwed. But remember, they are the cleanest shirt in a stack of dirty laundry. If you are reading this and you live in a U.S. or Canadian city, your municipal corporation is almost certainly in worse shape. What do we do about it?

What can we do now?

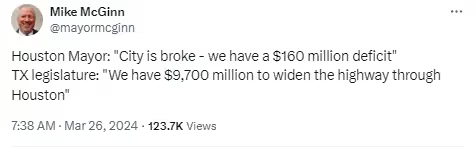

We spend every day working on that answer here at Strong Towns, but let me share an insight from another mayor, this one the former mayor of Seattle, now the Executive Director of America Walks (an organization that is definitely part of the answer). Here was his response to Houston’s financial shortfall.

Mayor McGinn has been through this himself. His city had a chance to spend less money on a project to convert the Alaska Way Viaduct from an elevated highway to a connected boulevard, redirecting billions of dollars of public funding from highway construction into transit and walking/biking infrastructure. The move would have saved billions and induced many multiples of that in private investment, making Seattle simultaneously wealthier and a better place to live. He ran on that platform, won a mandate, and then faced the unstoppable wave of state and federal transportation funding.

McGinn lost. Seattle lost. Ten billion dollars later, traffic in the new tunnel is down 23% and the city is still paying for unanticipated cost overruns.

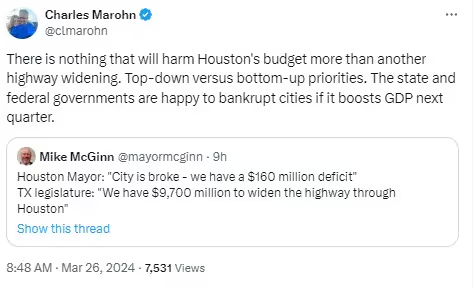

Here’s my response to McGinn.

The federal government is more interested in next quarter’s economic statistics than they are in the long-term health of your city. Ditto with the state government. That is not an anti-government statement; it’s an observation of what their financial incentives are (follow the money). The state and federal government mostly tax transactions and so an economy that generates a lot of transactions is going to make their life easier.

Cities don’t work this way. Cities need to build wealth in their neighborhoods in order to sustain themselves. A local government can’t spend a dollar providing street access to a property where they only get 20 cents in return. Well, they can do it, but it will catch up to them eventually.

Here’s the key: state and federal governments will pay cities all day and every day to make bad financial decisions and transactions that are not in the broad financial interest of their own residents. They have lots of programs to do this, highway expansions being just one of them. It’s not that state and federal officials are evil; they are just not sensitive to the financial ramifications of these transactions. And to be fair, cities are generally insensitive to them as well (even though they bear the long-term burden).

Fundamentally, that is what needs to change. As local leaders, we need to become more sensitive, more aware, of the financial implications of our development pattern. Here’s the good news: we can easily do that. We don’t have to ignore the long-term liabilities. We don’t have to do projects that make us poorer. We’re not powerless.

You are not powerless.

Strong Towns is a movement to make our cities financially strong and resilient. We have developed an entire set of responses to this challenge, with more coming all the time. If you’re just finding us, it’s not too late to get started. Let us know where you’re struggling—use the comment section below—and we’ll try and point you in the right direction.