On the Outside, Looking In

Pete Saunders is a planning consultant and journalist based in Chicago. He blogs at The Corner Side Yard and today's article is republished from his blog with permission. You can also catch Pete's recent interview on the Strong Towns podcast.

Mayor Sylvester "Sly" James of Kansas City, MO is one of only a handful of African American mayors in America's largest cities. (Source: BlindManEditing)

The urban political base that was the foundation of African-American politics since the Civil Rights Movement is slowly eroding. Because of large-scale demographic trends at work in our metro areas, black political influence is in decline. Unless blacks become more inclusive (or intersectional) in our political approach, or better at building coalitions, we risk having our political concerns relegated to the margins, by virtue of where we live.

I said as much nearly three years ago in my essay, "How 'Black = Urban' Ends," and in subsequent posts I wrote nearly two years ago about urban and suburban demographic trends and how that's reflected in our metro areas. I haven't updated the data, but think the trends are more evident now than ever.

How can I make this claim? One measure is the number of elected African-American mayors in our nation's largest cities.

Let's look at how things have changed over the last 25 years. In 1992, four of the ten largest cities in the nation were led by black mayors (New York, Los Angeles, Philadelphia and Detroit). Some cities, like Chicago and Cleveland, had already elected black mayors but no longer had them; others, like Seattle, Denver, Kansas City, Memphis, Minneapolis and San Francisco, would elect their first black mayors before the end of the decade. In all, by 2000, 13 of the 25 largest U.S. cities at the time, and 19 of the 50 largest, either had or would have a black mayor in office.

But the election of black mayors in large cities would slow greatly after 2000. Today, only six of the 50 largest cities (Houston, Denver, Washington, DC, Baltimore, Kansas City and Atlanta) currently have black mayors. Five more cities in the top 50 -- San Antonio, Jacksonville, Columbus, Sacramento and Wichita -- had black mayors whose terms started in 2000 or later, but have since been replaced (most recently former San Antonio Mayor Ivy Taylor, just last month).

Let's be clear about a couple things, however. While the numbers of black mayors of large cities has declined over the last 25 years, the leadership of our cities is far more diverse -- and representative -- than it was then. There are more Latino, Asian and female mayors leading our large cities than ever before, and that's a positive. But that doesn't change the fact that there are fewer blacks in those positions.

And while the election of big city mayors is relatively easy to track, identifying trends among other local officials is far more difficult. My guess is that city councils, county boards, special service districts and the like are also more diverse and representative, and may even have more African-Americans in those positions -- even as the number of black mayors has declined. That also can be viewed as a positive.

The Explanation

How can this be explained? Two years ago I pulled some Census Bureau ACS data for the twenty largest U.S. urbanized areas (the contiguous portions of metro areas with more than 1,000 people per square mile) that offered some interesting findings:

- Nationally, principal cities and their suburbs both grew at 4.4% between 2010 and 2014.

- Metro area population growth is driven by strong growth among Hispanics, Asians and other groups.

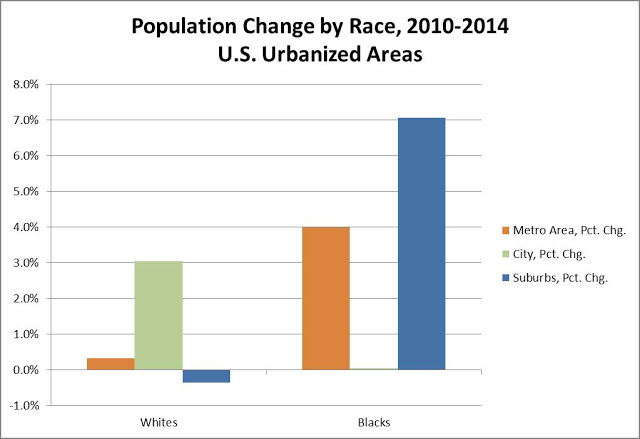

- Within urbanized areas, however, whites and blacks are growing at much slower rates – blacks at 4.0%, whites at just 0.3% nationwide.

- Within the twenty largest urbanized areas, the number of white residents is growing in principal cities and decreasing in suburbs.

- Similarly, the number of black residents is growing in suburbs, and essentially flat in principal cities.

- At the metro level, 12 of the top 20 metro areas have principal cities where the white population is increasing while the black population is decreasing, or where the growth rate of whites exceeds that of blacks.

- Similarly, 19 of the top 20 metro areas have suburbs where the black population is increasing while the white population is decreasing, or where the growth rate of whites exceeds that of whites.

Here's how that information looks graphically. First, for whites, blacks, Hispanics, Asians and others, at the national level by city and suburban geography:

And then, a focus in on whites and blacks nationally, by city and suburban geography:

Now, let's look at percentage changes of whites and blacks within the principal cities of the twenty largest urbanized areas:

And lastly, at percentage changes of whites and blacks in suburban areas of the top 20:

This data is in need of updating, and there is the question of whether trends evident within the top 20 urban areas are applicable to smaller ones. I'll try to answer both when I can. In the meantime, simply put, Latino and Asian populations are growing in the largest cities and suburbs. Whites are growing more numerous in cities while declining in suburbs, while blacks are declining in cities and growing in suburbs.

This is the first part of understanding the change in African-American political influence.

“I want to dispel any notion that displacement related to gentrification plays a dominant role in this. That’s the narrative that’s fueled gentrification debates for years. But rarely does this narrative consider the aspirational appeal of moving to the suburbs that still resonates with many people of color, just as it did with earlier generations of whites in the 20th century.”

Much of this seems to slip under the radar of urbanists, because of the second part of trying to understand this -- your level of analysis impacts your ability to perceive, and evaluate, the trend. At the metro level, we see that suburbs are becoming more diverse as they add more people of color and cities see a return of white residents to core cities. After generations of practices put in place to exclude people of color from suburbs, this is applauded. But at the neighborhood level, it could be viewed quite differently: an influx of minorities where none previously existed in the suburbs, or an influx of whites in minority-dominated neighborhoods. Only one of these trends at the neighborhood level has truly been considered by most urbanists.

Speaking of which -- I want to dispel any notion that displacement related to gentrification plays a dominant role in this. That's the narrative that's fueled gentrification debates for years. But rarely does this narrative consider the aspirational appeal of moving to the suburbs that still resonates with many people of color, just as it did with earlier generations of whites in the 20th century. Lance Freeman, a professor of urban planning at Columbia University, has conducted considerable research that counters this assumption:

"What distinguishes gentrification is not who moves out; it’s who moves in. In a gentrifying neighborhood, new residents are more likely to be well-off. As a result, the neighborhood’s poverty makeup can shift, even if no one leaves. In 2004, I found that a neighborhood’s poverty rate could drop from 30 percent to 12 percent in a decade with minimal displacement. That’s because gentrification often leads to new construction or to investment in once-vacant properties."

Thinking that gentrifiers are forcing this dynamic magnifies their importance, and diminishes the decision-making process of people of color.

The Impact

Back to politics. What will this mean going forward, given what we know about how cities are changing the political landscape? We know that cities are pushing forward to develop an urban political agenda; in the aftermath of the election of Donald Trump to the presidency, a key recommendation of Richard Florida's book The New Urban Crisis was that cities should become more autonomous so they can more effectively address the challenges that impact them. But with increasing numbers of minorities in suburbia, and a growing number of urbanists who have "been there, done that" when it comes to the suburbs, does autonomy come at a price?

Here's how I see things playing out over the next decade or two. People of color will continue to move to suburbia in increasing numbers. They will do so for the same reasons people before them did -- affordability, good schools, lower crime. They are doing so in part because suburbia is something that eluded them for so long, and is now within their grasp. As they move in, they will begin to wield more influence on suburban politics -- suburban mayors, County Board representatives, more representation in state legislatures. We will see more minority representation in the suburbs -- just as suburban political influence wanes.

Why? Because cities are ascendant. It's not just people flowing back into cities. It's jobs, and it's money. More and more people in residential and commercial real estate are finding out that the real money to be made is now in cities. Banks will change lending patterns to favor cities, and not suburbs. The case will be made -- and rightly so -- that urban density is the right response to lowering carbon emissions in a climate change world, and those who choose density will be rewarded. At the same time, those who choose sprawl will be punished. Banks won't finance new development or renovations. Property values will decline. Tax dollars for infrastructure improvements will be harder to come by.

I hardly see this happening to all suburban areas across the country. There are suburbs in some metro areas that are closely aligned with the core city (either by adjacency or transit) and will adapt accordingly. There are pockets of affluence in many suburbs that will not change, no matter what broader trends portend. There are other metro areas whose entire makeup is largely suburban in orientation, and any change they have will more likely be region-wide. As for metro areas with a bigger city-suburban divide, over time I see wealth being pulled from suburbia and back into cities in quite the same way it happened in the middle of the 20th century, in reverse. Minority political representation will continue to decline in cities and increase in suburbs -- and they'll find they own a landscape few people want.

In other words, even as people of color are making decisions that work in their interests now, we may need to get accustomed to a future of being on the outside, looking in.

(Top photo by Liz Zimbelman)

Small-scale, incremental development works in the suburbs too, if we let it.