Keeping the Dream of the 60s Alive

Today, we focus on Washington transportation funding, and here to kick us off is Paula Reeves, city planner and president of the American Planning Association's Washington chapter. Paula is a member of Strong Towns and spent twenty years at the Washington State Department of Transportation.

Photo by Brandon Bartoszek

While more State Departments of Transportation (DOTs) leaders are talking about multi-modal transportation, their ranks seem to be digging in, committed to keeping the dream of the 1960’s alive.

With pressure from State DOT’s, both federal and state policy makers continue to kick the can down the road passing more funding to highway expansion projects in spite of shifting public opinion and mounting evidence that they cannot afford to maintain the roads and transit systems in place today.

State DOTs pass on a relatively insignificant amount of specified federal funding to regional agencies, cities and counties for community transportation projects like sidewalks, crosswalks, trails or bike lanes as a result of federal requirements (about $835 million of the $305 billion transportation budget or .3 percent). However, when there is flexibility or latitude in federal funding programs, State DOTs most often opt to pay for roads or underfunded maintenance of roads first. This trend is likely to continue as the FAST Act, the federal transportation funding bill that passed in 2015, provides additional funding flexibility to Regional Transportation agencies. The insubstantial amount of funding that does go to smaller community safety and accessibility connections like sidewalks, crosswalks or bicycle facilities is not nearly enough to turn the tide and provide the kind of urban transportation systems that will be necessary in the coming decades.

“Washington, known for having one of the “greenest” administrations, just passed the largest transportation spending bill in the state’s history.”

Let’s look more closely at my home state of Washington, as just one example. Washington, known for having one of the “greenest” administrations, just passed the largest transportation spending bill in the state’s history. It was signed into law by Governor Jay Inslee in July 2015, a 16-year, $16 billion dollar highway spending bill touted as a solution to congestion and jobs. This transportation bill includes less than 2% of total funding to improve conditions for biking and walking with no apparent rhyme or reason. In Washington cities, just as many people are biking and walking as take the bus/rail, and bicycle and pedestrian traffic fatalities are now as high as 30% of all traffic crashes. A disproportionately high number of these traffic crashes occur on state highways that are also city streets because they are generally designed for higher vehicle speeds through community centers.

Where are the strong public interest groups in Washington that advocate for sustainability, environmental responsibility, safer routes to schools, active transportation? Not wanting to rock the boat with politeness to a degree only seen in the Pacific Northwest and still fearful of losing the pittance of funding they have managed to squirrel aside or earmark, Washington’s public interest organizations come out in favor of these completely unsustainable highway bills.

Here are five themes backing up the assertion that State DOTs are keeping us stuck squarely in the 1960’s, and without leadership and significant change, our nation’s transportation paradigm is stuck too…

1. The Bigger, The Better

The culture within State DOTs promotes and awards the biggest highway projects. The best project managers and best engineers serve on the “Mega” project teams. Small local community safety improvement projects are for the lesser, junior engineers. This thinking influences regional and local engineers making it difficult to get any level of government to spend adequate time or funding on the smaller connections that can have some of the biggest impacts.

One example of the kind of community transportation solution that should reframe this ‘bigger is better’ culture was completed recently in Bonney Lake, WA. A small trail connection with a $1 million price tag linked schools with a sizable residential area enabling the school district to cut back a number of school bus routes. This project was extremely popular in the community and paid for itself immediately.

2. State Transportation Planning = Marketing

Seldom, if ever, will you see a State DOT Plan of any kind that does not advocate for developing the next big transportation project(s) that will continue to employ their large workforces.

Looking again at Washington State as an example, funding for corridor planning this biennium (2015-17) is dedicated largely to projects on the fringe of urban areas that increase road capacity. Recent WSDOT research found that where the DOT does construct projects on State Highways that are also City Streets, these projects often result in scope, schedule and/or budget changes costing on the order of $9 million per project. Some may argue that regional and local agencies should be the agencies to take up corridor planning on these state highways if community connections are to be the focus. However, this is unlikely as many State DOTs approve designs and cities have very limited resources for planning or project development.

Partnership should be a priority for both state and federal transportation planning funds, but DOTs are still going it alone for the most part and as a result they are failing to objectively evaluate a full range of alternatives.

3. “Practical” Design?

“Using distorted images to downplay the visual impact of massive freeways has a long tradition in US engineering practice. It was a tactic honed to perfection by the master builder himself, Robert Moses, in New York more than half a century ago.”

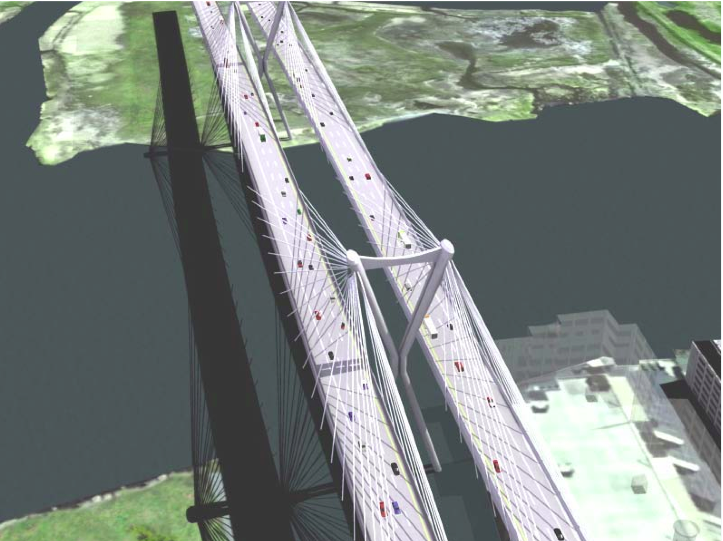

Artist rendering of a proposed bridge between New Jersey and New York. Image from Wikimedia.

‘Practical Design’ is a new term for an old approach. It is being used as a tool to make highway capacity projects look more appealing and affordable, and may enable State DOTs to continue the same unsustainable highway building paradigm for another decade, if successful. Its proponents seem sincere and even critical of the past, but, make no mistake, this is more of the same.

Some State DOTs, in an effort to stretch maintenance dollars and avoid making connections or federally mandated accessibility improvements are going so far as to pave only the interior lanes of State Highways that are also City Streets or avoiding these maintenance projects altogether.

4. Transit ≠ Multi-Modal

Transit “Mega”projects like fly over ramps, tunnels, and freeway expansion for High Occupancy Vehicles (2+ occupants) continue the road building paradigm and have removed pedestrian connections, stripped off bike lanes, and severed community connections in the same way that traditional road projects have changing community development patterns.

As BikePortland points out in a recent post, biking and transit are similar in terms of total trips in many cities across the US, while biking and walking improvements are an afterthought and receive only about 1% of the funding that goes to transit. It is evident that transit, biking and walking investments can in some cases be complementary, addressing high priority needs for all three modes. However, these projects are often competing for the same limited resources. More emphasis on evaluating the costs and benefits of transit investments compared to bicycle or pedestrian investments is needed.

5. Staffing Their Talk

Take time to look at the League of American Bicyclists’ ranking of State DOTs. The League finds that State DOTs, on average, dedicate less than one full time employee to the role of improving conditions for biking and walking and in most cases these staff are within Planning or Traffic Divisions. Some State DOTs report having multiple offices involved in multi-modal transportation. It is unclear what this means in terms of accountability and in these cases bicycle and pedestrian traffic fatalities are still on the rise.

Here is a final thought summing up State DOTs and their efforts to maintain the status quo in road building in spite of talking a good game about multi-modal transportation. I recently had the opportunity to attend the 60th Annual National Transportation Management Conference hosted by the American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials. What I heard at this invitation-only meeting for America’s state transportation leaders terrified me; self-driving vehicles and drones are our nation’s transportation future. There is no paradigm shift in their vision. No change is anticipated or seen as necessary.

Is this what is really best for the nation, our states, or our communities? We must explore this question in a national dialog that is independent of transportation agencies. If we don’t, these agencies, still pushing toward goals established in the 1960’s, will most certainly answer it for us.

(Top photo by Rex Gray)

Related stories:

Paula Reeves, AICP CTP has been planning and developing community transportation projects for the state, cities, counties, and transit agencies for over twenty years. She recently became City Planner for Tumwater, Washington after nearly 20 years at Washington State Department of Transportation providing a range of transportation planning and engineering services to help develop more livable communities. Paula also serves on the National Transportation Research Board’s Pedestrian and Bicycle Committees, the American Institute of Certified Planners’ Community Planning Task Force, is President of the American Planning Association Washington Chapter, served on the Board of Directors for Puget Sound Bike Share, and is a practicing mediator in Thurston County.