Best of 2016: Pre-Election Thoughts

Our traffic this year is more than double what it was a year ago. I'm extra proud of that fact because you never saw from us the kind of cheap election-year click bait that you got from other places. We certainly weren't politics free, but -- consistent with our overall approach -- we are not defined by America's binary political paradigm. I've always argued that there are perfectly acceptable ways to be a conservative and a Strong Towns advocate and there are also perfectly acceptable ways to be a progressive/liberal and be a Strong Towns advocate. That may make us less relevant to partisans who want a continual feed exclusively bashing/supporting one side or the other, but hopefully more relevant to what actually matters.

I wrote this piece the day before the election. One line has come back to me over and over again in the weeks since.

My friends, you will not get a Trajan without the occasional Nero.

We've long argued here that concentrated power allows us to accomplish a lot in a short period of time, but we give up the ability to innovate, get constructive feedback or acknowledge local nuance. Many Americans who advocate for a stronger, centralized power structure to accomplish their goals are now waking up to the downside of that approach. For example, the ability to filibuster legislation in the Senate was inconvenient when your side wanted legislation passed, but now that the filibuster is gone, those who fought to get rid of it may wish they hadn't. The same goes for executive orders, a power that has been continually expanded to now do some really dramatic things. Executive orders by your guy are great. The other guy: not so much.

I know that emotions are still raw, battle lines still dominate and it looks like the only thing predictable about the next four years will be the day-to-day unpredictability. I have come to respect -- if not fully understand -- the sense of fear that many now have. I hope those fears are ultimately unfounded, but I know we have quite a bit of stress to go through before we get to something stable. In a recent comment, I suggested the following way to think of the Suburban Experiment:

1945-1970 America: Growth through top down initiatives, the exercise of centralized power (interstate system, home mortgage system, urban renewal, etc...)

1970-1995 America: System inertia sustained with debt

1995-20?? America: Desperation at all levels to avoid the consequences of past decisions (crazy finance, stimulus, ZIRP, quantitative easing, etc...)

20?? America: Reset, local systems fill the void left by the successive failures of centralized authority

Just like soldiers walk a fine line preparing for a war they shouldn't want to ever happen (but partially hope it does), I'm keenly aware that there is sometimes not enough distinction between preparing for a reset and hoping for one. I'm not going to predict when we will make that transition -- after all, in 2008 I would have incorrectly predicted it for 2009 -- but I feel like it is inevitable. I also feel like it will be painful, crazy and more than a little surreal, kind of like what we are experiencing right now. There may come a day when we look back at 2016 as quaint.

Martin Luther. Image from Wikimedia.

I'm in what we call here in Minnesota a "mixed marriage" -- I'm Catholic and my wife is Lutheran -- and, by way of being a godparent, I found myself in a Lutheran service on Reformation Sunday, the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation. I spent the time during the frequent and excessively long bouts of singing pondering the social conditions that surrounded the Reformation and Martin Luther's role in catalyzing them.

A simple reading of history would have us believe that Martin Luther was annoyed with the Pope, wrote out some complaints and nailed them to the church door and then -- after a period of some anxiety -- started holding church services with the previously alluded to emphasis on the singing of hymns. In fact, I would have believed this myself today if I had never read the book, Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling, which touched off a vein of curiosity on the topic that I've still not satiated.

The reality is that Martin Luther came after a long line of reformers had stood up and were summarily put down for the transgression of speaking out. Many were burned at the stake for heresy, including John Wycliffe, whose writings questioning church doctrine proved so influential that, three decades after his death, his body was exhumed for the sole purpose of burning it (that will teach him). In the context of a long struggle, the most unique thing about Martin Luther was that he survived -- thanks to the protection of some nobles who were also unhappy with the church -- and was able to spread his message (props to Gutenberg).

In a vacuum, the Reformation makes no sense. This was, after all, a rebellion against God, at least as most at the time understood divinity. What made the fire of Reformation successful was the kindling of a beleaguered population. I try to imagine what religious life would be like for your standard man or woman in the 1400's. A man who is sworn to a life of poverty and virtue, yet is clearly living the most luxurious (and often debauched) life imaginable in your town, would interpret for you the word of God, which is written in a language you cannot read or understand. Those interpretations would affirm your lowly social standing, and his higher standing -- as well as that of the ruling class -- as the will of God. You would then need to visit this man regularly in private where you were expected to confess all of your sins -- not only deeds but sinful thoughts -- or risk eternal damnation. Of course, with a generous contribution of gold (money you did not have but others seemingly did) you would be able to shorten the term of suffering you would experience in the afterlife.

One of Martin Luther's unforgivable transgressions was translating the bible into German. Imagine the shock of finally being able to read the word of God for yourself and, in doing so, learning that Jesus seemed a lot more peasant-like than you had been led to believe. Millions would die in the Reformation, that kindling set aflame as the ruling elite fought to retain or gain power. Sitting in my comfortable pew on a beautiful Sunday morning, it's hard to say that level of carnage and suffering was worth it.

Image Creative Commons by Count to 10

Yet, it's also hard to see another way it could have unfolded.

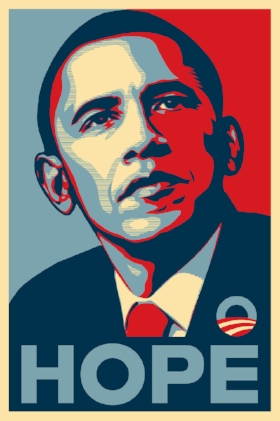

I started writing what would later become Strong Towns in November 2008 after, what seemed at the time, a miserable election season. Funny how quaint it looks now. Despite the feeling of hope and change that year, the candidates and their parties were silent, where they weren't overtly hostile, to the issues I felt most important. Writing for me was a form of therapy, a way to express my thoughts in a world that I thought was spinning off into crazy land.

Major banks and insurance companies failing because they made really dangerous and risky decisions and then getting bailed out by the government. The Federal Reserve buying up every home mortgage they could get their hands on. Stimulus spending targeting the most worthless and destructive set of old school infrastructure projects just because they were "shovel ready". Interest rates at zero. ZERO! And all of this craziness was bi-partisan, opposed by only a small group of people on the kook fringe of each party.

Geography has given me a number of unique insights, revelations forged through the pain of having to resolve conflicting viewpoints I find equally compelling. I live in an old, declining town right next to a shiny new suburban city; I've been able to watch the Illusion of Wealth play out in high fidelity due to a natural experiment that exists in few other places. I grew up on a farm but live in a city. I was in the Army but am more of a civil liberties than a law-and-order guy. I grew up dirt poor but now make a nice professional living. I'm an engineer (left brain) and a planner (right brain). And, politically, I live in a Blue dot in a Red region of a consistently Blue state.

When it comes to presidential elections, my head understands Blue, but my heart bleeds Red.

I've long turned off cable news and political talk radio; I think we would all be better off without it. What I can't escape -- although I take a weekly 24-hour social media sabbath -- is Facebook. While social media has been criticized for narrowing the range of ideas we are exposed to, that is only because we tend to be friends with people like ourselves. I'm fortunate to have a broad range of friends from many different places, but during election season that means I get an equal amount of this (and these are not my friends but I've chosen them because they represent what I see routinely in my feed).

Since I spend most of my time here sharing things of the head, I'm going to give you a little bit of the heart today. My hope is that, regardless of what happens tomorrow, we can all realize that -- despite what the ruling class of our day wants us to believe -- we peasants have a lot more in common with each other than with them. The discontent out here is real and justified, although not always well-directed. While I don't see a way the bloodbath of the Reformation could have been avoided, I do see some paths for our transition from unstable extremes of wealth and power to be less messy than it seems to be trending. Each hopeful path begins with understanding.

For me, Cracked -- yes, I said Cracked -- had the best piece of the entire election cycle explaining Trump voters: How Half of America Lost It's F**king Mind (and don't read it if you are overly sensitive to curse words). I nodded my head the entire way through. The very first point -- it's not about red and blue states, it's about the country versus the city -- reminds me of the American Civil War, where the two clashing economic systems of the industrial North and the plantation South were "resolved" in favor of the stronger. The way we culturally view each other today has similar contrast (although the outcome of the present clash is less in doubt). From the article:

People living in the countryside are twice as likely to own a gun and will probably get married younger. People in the urban "blue" areas talk faster and walk faster. They are more likely to be drug abusers but less likely to be alcoholics. The blues are less likely to own land and, most importantly, they're less likely to be Evangelical Christians.

In the small towns, this often gets expressed as "They don't share our values!" and my progressive friends love to scoff at that. "What, like illiteracy and homophobia?!?!"

Nope. Everything.

When I listen or read Vox -- and I do listen to a couple of their podcasts regularly because Malcolm Gladwell told me to -- I often find myself yelling at the stereo, "Get a f**king clue!" I get them -- I intellectually understand where they are coming from and what makes them see the world the way they do and I respect it -- but they don't get me. More importantly, they don't have a clue about the people I grew up with and continue to live with as neighbors. Not. A. Clue.

Again, from Cracked:

“Where I’m from, you weren’t a real man unless you could repair a car, patch a roof, hunt your own meat, and defend your home from an intruder. It was a source of shame to be dependent on anyone — especially the government.”

These are people who come from a long line of folks who took pride in looking after themselves. Where I'm from, you weren't a real man unless you could repair a car, patch a roof, hunt your own meat, and defend your home from an intruder. It was a source of shame to be dependent on anyone -- especially the government. You mowed your own lawn and fixed your own pipes when they leaked, you hauled your own firewood in your own pickup truck.

The rural folk with the Trump signs in their yards say their way of life is dying, and you smirk and say what they really mean is that blacks and gays are finally getting equal rights and they hate it. But I'm telling you, they say their way of life is dying because their way of life is dying. It's not their imagination. No movie about the future portrays it as being full of traditional families, hunters, and coal mines. Well, except for Hunger Games, and that was depicted as an apocalypse.

If you'd like this explained in a more intellectual way, Radio Open Source with Christopher Lydon has done the best reporting that I've seen on the issue. Lydon is a traditional liberal but has a curiosity and level of compassion that I have found makes him keenly insightful. Specifically, his podcast 'Secular Rapture': Trump and the American Dispossessed was particularly good. I shared it with a number of my left-of-center friends (the open minded ones) and the response was positive. I think I understand now. That episode included J.D. Vance, the author of Hillbilly Elegy: A memoir of a family and culture in crisis, and Arlie Hochschild, author of Strangers in their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right, both books that will be on my recommended reading list at the end of the year.

The latter book had a discussion on environmental regulations that felt very Strong Towns to me. It paralleled some of the points I have been trying to make (with lots of resistance) over the past few weeks about development in Portland. Hochschild writes:

"If your motorboat leaks a little gas into the water, the warden’ll write you up. But if companies leak thousands of gallons of it and kill all the life here? The state lets them go. If you shoot an endangered brown pelican, they’ll put you in jail. But if a company kills the brown pelican by poisoning the fish he eats? They let it go. I think they overregulate the bottom because it’s harder to regulate the top.”

In big cities, it's easier to skew things towards "the top" because it's harder, messier and -- with the way government is set up today -- just way more difficult to work at the bottom. I understand the passionate arguments of those who think I've somehow lost it on Portland -- that I've suddenly become ignorant and in need of a big city enlightenment -- yet I feel I had a lot more I common on a personal level with the (non-professional) people I met there. At one point, as we were getting the professional tour of all the greatness that (supposedly) is Portland's TOD development, I turned to one of them and softly said, "This is a bunch of crap, isn't it." He gave me the shrug and nod, a universal signal I've known since my youth on the farm and perfected as a private in the Army. Yeah, it's crap, but what do you do?

Well, what do you do? I wrote a while back about how the size and scale of Red America and Blue America had a huge impact on how one views the effectiveness of government. In small towns, in politically red areas, the largest employers are frequently governments. The highest paid professionals work for government, the most secure jobs with the best benefits are with the government and the largest force impacting the direction of the city is the government. And, as I noted earlier, these places are really struggling, which makes the biggest player (government) a real easy target. None of this is true in big cities, especially in the places occupied by the country's professional class:

If someone lives in a place dominated by state/fed money, where progress is continually thwarted by state/federal mandates, it is not hard to imagine where the healthy skepticism of government would originate. Conversely, if someone lives in a place where the state/federal governments are less important players, where they often serve as a difference-maker in achieving locally-established goals, it is easy to understand why such a person would look more favorably on state/federal interventions.

Intellectually, I've always struggled to understand Democratic voters as they relate to the presidency. Whether Bob Dole, George W. Bush, John McCain (and Sarah Palin), Mitt Romney or Donald Trump, every four years we're told that electing a Republican will mean the apocalypse. Seriously, can we really have a madman such as that running this country? Yet, straight ticket Democratic voters consistently vote for people and policies that strengthen the role of centralized government and give more and more power to fewer and fewer people. My friends, you will not get a Trajan without the occasional Nero. If Nero destroys all you have worked for, shouldn't the obsession be Nero-proofing the government (making it smaller and the power more distributed)?

“The modern bible is not only written in a different language, they are keenly aware that the people interpreting it for them don’t truly have their best interests at heart.”

The poor people of this country -- red and blue voters alike -- have far more in common with each other than with the governing elite, the professional class and others who are doing well in the current system. Whether it's the dislocated I met in Portland who have no future at a TOD, those getting pushed aside in Shreveport to make way for a new highway or those living in my hometown who can't safely walk to the store yet are on the hook for millions for a sewer and water expansion meant to create growth, the system is not working. And it's not going to work for them. There is no amount of job training, tuition credits or housing programs that will get them beyond living paycheck to paycheck. There is no tax structure or subsidy regime which will give them dignity. The modern bible is not only written in a different language, they are keenly aware that the people interpreting it for them don't truly have their best interests at heart.

What will give them dignity, what will give them a real chance, is an economy scaled to them: One that operates at the block level, not at the mega region. One where a TOD site doesn't sit empty for decades waiting for the high density mega-project while food trucks and starter shacks face mounds of regulatory bureaucracy. One where we choose to mend our sidewalks instead of expand our highways. One where neighborhood resiliency is prioritized over Walmart efficiency.

I've traveled this country for years now. I've spoken to more people and seen more of the good and bad than just about anyone. What this country needs, what can unite us, is a Strong Towns approach. We will have a strong and prosperous nation only when we have strong cities, towns and neighborhoods. That kind of prosperity cannot be imposed or engineered from the top; it must be built slowly from the ground up. Scale our economy to those working at the ground level and we will see a true prosperity emerge from the fear and acrimony that is our national dialog.

Regardless of how you vote tomorrow, let's work each and every day to empower those who are trying to build a strong town.

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.