The power of growing incrementally

I’ve found that the most difficult thing for people to grasp about Strong Towns is our insistence on an incremental approach to development. In the Curbside Chat, I stress how we need to be making small investments over a broad area over a long period of time. I talk about the small bets our ancestors made when building places, how their approach fit with a complex world where we lack the ability to predict, project or even fully understand, after the fact, why one place succeeds and another fails. I show how the incremental approach results in places that are resilient, adaptable and – most incredibly – financially far more successful than our modern approach.

I’ve shared all this in person with thousands of people. I’ve watched their minds explode with new insight and understanding. I’ve seen their heads nod while their faces smile. And then I’ve watched them leave only to – as we say here at Strong Towns – try and achieve Jane Jacobs ends through Robert Moses means.

For modern Americans, incremental is just so hard.

Part of this is modernity. Before our Suburban Experiment, people around the world didn’t build incrementally because they were wise. They built that way because, for the most part, they didn’t have another option. They lacked the resources and technology to move mountains, actually or metaphorically. When Daniel Burnham suggested in 1907 that we should, “make no little plans,” he was at the beginning of a century where that quote would be interpreted to mean, “take no little actions.”

“We don’t go to a doctor seeking to be told we must eat healthy, exercise and have good sleeping habits. How uninspiring!”

So whether it is Robert Moses then or Elon Musk today, people who would have – in a time past – been called charlatans or hustlers, now become deeply admired for their willingness to take bold action (with public money or supported by tax subsidies). We don’t go to a doctor seeking to be told we must eat healthy, exercise and have good sleeping habits. How uninspiring! Neither do we look to our elected leaders or the cadre of professionals we have turned our cities over to to have them tell us they will generally keep things in working order, establish some reserve funds and make modest improvements, where possible.

Yet, incremental investment is how cities have always built wealth. It’s also why places that are the antithesis of the diet and exercise approach – places like Portland and Austin, to name two I’ve discussed at length – are so confusing and disturbing to me. Portland does not make sense to me. Austin does not make sense to me. Wide swaths of the places that are held up as urbanist success stories, places we’re told that Jane Jacobs would be proud of – places like New York City and San Francisco and Boston and Toronto – don’t make sense to me.

They feel like illusions—like a beautiful model who looks terrible without her makeup. Like someone driving a convertible that’s about to be repossessed. Like a freshly planted flower bed set in bad soil. My friends and colleagues cheer these places for their vitality and growth, but it feels wrong to me. The financial foundation of it all feels wrong to me. This week I’m going to try and explain why.

There are two defining differences between pre-Depression and post-War development patterns. Pre-Depression development was incremental on a continuum of improvement while post-War development is built at a large scale to a finished state. Forget the car, the suburbs and the big box store – the symptoms we obsess over today – and just focus on those two aspects.

Below is the example from the Curbside Chat of what it means to build incrementally. These are three photos from my hometown. The first is a series of popup shacks from around 1870. As with every pre-Depression city in all human history, this is how things start. That includes not just Brainerd but Manhattan and Dallas and San Francisco and Charleston and Paris and Rome. They all started as little popup shacks. They all began as a small, incremental investment tied to hopes and dreams about the future.

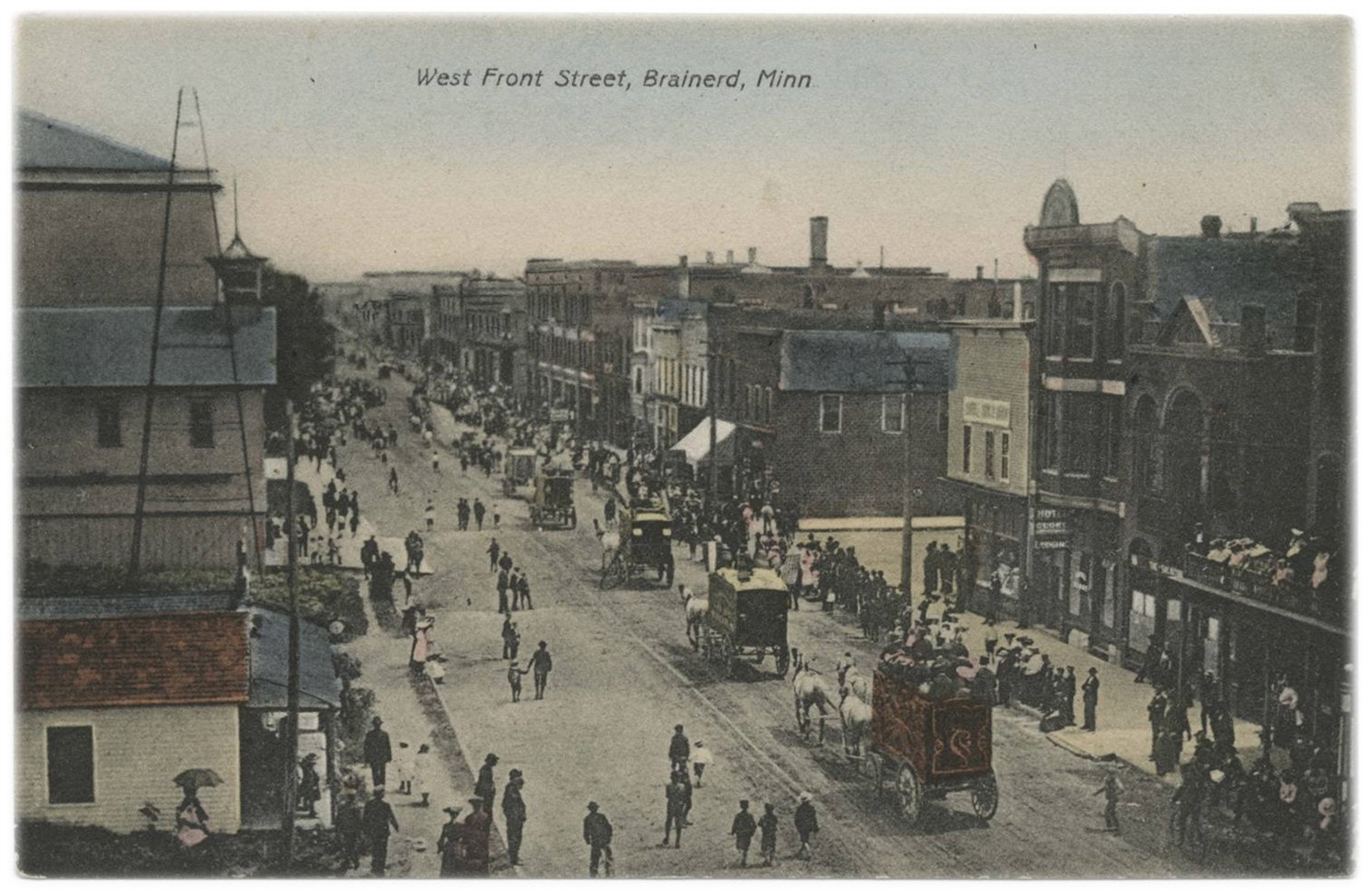

The second photo is the same street in 1904. While many cities never got beyond the popup phase, many grew incrementally like mine and saw those shacks replaced by more substantial structures. Note that out on the edge of town there would have been a collection of popup buildings like the ones in the heart of town in 1870.

This third photo is from around World War II. Those two and three-story wood structures have been replaced with buildings of brick and granite. Go a few blocks in any direction and the development pattern has the intensity of the 1904 photo and, a few blocks beyond that, there were popup shacks.

If we were to do a graph of tax value per acre for each of these time periods, this is what it would look like.

In each of these time periods, the center of town – the heart of the neighborhood that was being developed – had the highest values. The values declined as we go further from the core. In addition, in each subsequent iteration, the value is greater in each location. These fundamental economic relationships are the key driver of incremental development.

As a brief aside, it’s important to note that proximity is what creates the growth in value. The reason the popup shacks are positioned next to each other is because, in a time before automobiles, business owners wanted to be right next to other businesses. Home owners (who weren’t farmers) wanted to be near to town. And the nature of this development was complimentary; a business owner acting in their own selfish self-interest would line up their building with all the others, place their door on the street and make their building as ornate as possible. All this meant that, the more things developed, the more valuable everything else became.

Let’s examine the financial fundamentals that bring about the phase change from popup shack to 3-story wood structure. For simplicity, let’s assume this happened over thirty years. The chart below shows theoretical land values compared to the value of the shack – which I’m going to call the improvement value – for that thirty years between 1870 and 1900.

In 1870, the land wasn’t worth much. There was a railroad stop and some platted lots but not much settlement. Nobody really knew for sure how the town would fare so those who started there were early speculators and upstarts. They got cheap land and built a cheap building.

As the city grew and more cheap buildings were erected, land values started to climb. This was becoming more of a place and, as such, there was more demand (even if just slightly) to be there. Simultaneous with this, the structure – which was cheap to begin with – was depreciating in value. It probably didn’t have much of a foundation, the roof was starting to go bad and it would have become a maintenance problem. Land was going up in value while the improvement value was going down.

At some point, the land value would become substantial enough, and the improvement value cheap enough, to justify tearing down the structure and replacing it with something more substantial. This significantly increases the improvement value while helping propel the general upward trend of land values.

It is incrementally rising land values, combined with the ability to redevelop to something more intense, that naturally prompts the redevelopment of property in decline. Take away one of those two factors and redevelopment breaks down. Without redevelopment, there is a ceiling on success leaving only stagnation or decline as alternatives.

Having redevelopment potential puts a floor on decline – each iteration of growth becomes a resilient financial plateau that is hard to fall back from – and prompts continual neighborhood redevelopment to the next level of intensity.

Tomorrow we are going to look at the Improvement to Land Ratio (I/L) as an indicator of redevelopment potential. Later in the week we’re going to examine how the Suburban Experiment flatlined land values, thus destroying natural redevelopment and ensuring neighborhood decline. We’re also going to look at the ways land use controls and government growth projects (such as highway interchanges and government-led transit-oriented development) distort land values in ways that are truly destructive. Finally, at the end of the week, I’m going to suggest some ways we can get back to a healthy, incremental approach to development and make our places strong again.

Read the next article in this series: "The Little House, a Story of Incrementalism."

Many of incremental development’s values — localism, quality and civic pride — align well with those of houses of worship. If faith communities embrace this model, we could see a wave of faith-based housing that complements the broader movement toward incremental development.