California Housing Crisis

I was in Santa Rosa, California, last year doing a series of engagements with my friend Joe Minicozzi. We were chatting with some really smart people at one meeting when the topic of affordable housing came up. Here's how the conversation went:

Them: Housing is very expensive and it keeps going up. So many people want to be here that it's driving up prices so nobody can afford it.

Me: If they can't afford it, why do so many people pay it?

Them: Because housing keeps going up in value.

Me: Does anyone remember 2008? What was that like here?

Them: Oh it was really bad. Really painful.

Source: Public Policy Institute of California

For those of you still angry with me for not grasping (your simple and obvious explanation of) Portland's housing crisis, you might want to skip this article. I'm going to make some similarly ill informed observations and ask some patently ignorant questions about why this situation persists. My inspiration is an article on a website called CalWatchdog.com titled, "Democrats and Republicans see different solutions to California Housing Crisis." And, indeed, they do.

First, a handful of statistics. Nine years ago, California had the worst housing market in the United States. House prices were down by 27% and they just kept falling. A study released in March of 2008 by the Public Policy Institute of California painted a dramatic picture of boom and bust, and this was before things got really bad. There were many complicated and interrelated causes of the crash, a reality that gives every political ideology a set of narrow talking points they can dogmatically cling to.

Let's not focus on the bust, however, but instead focus in on the prior boom. If the prevailing narrative is to be believed, California is such an amazing place -- and, as a Minnesotan, I'm genetically predisposed to agree with that notion, particularly during January and February -- it's just so amazing that people can't stop moving there. This huge amount of demand is driving up the price.

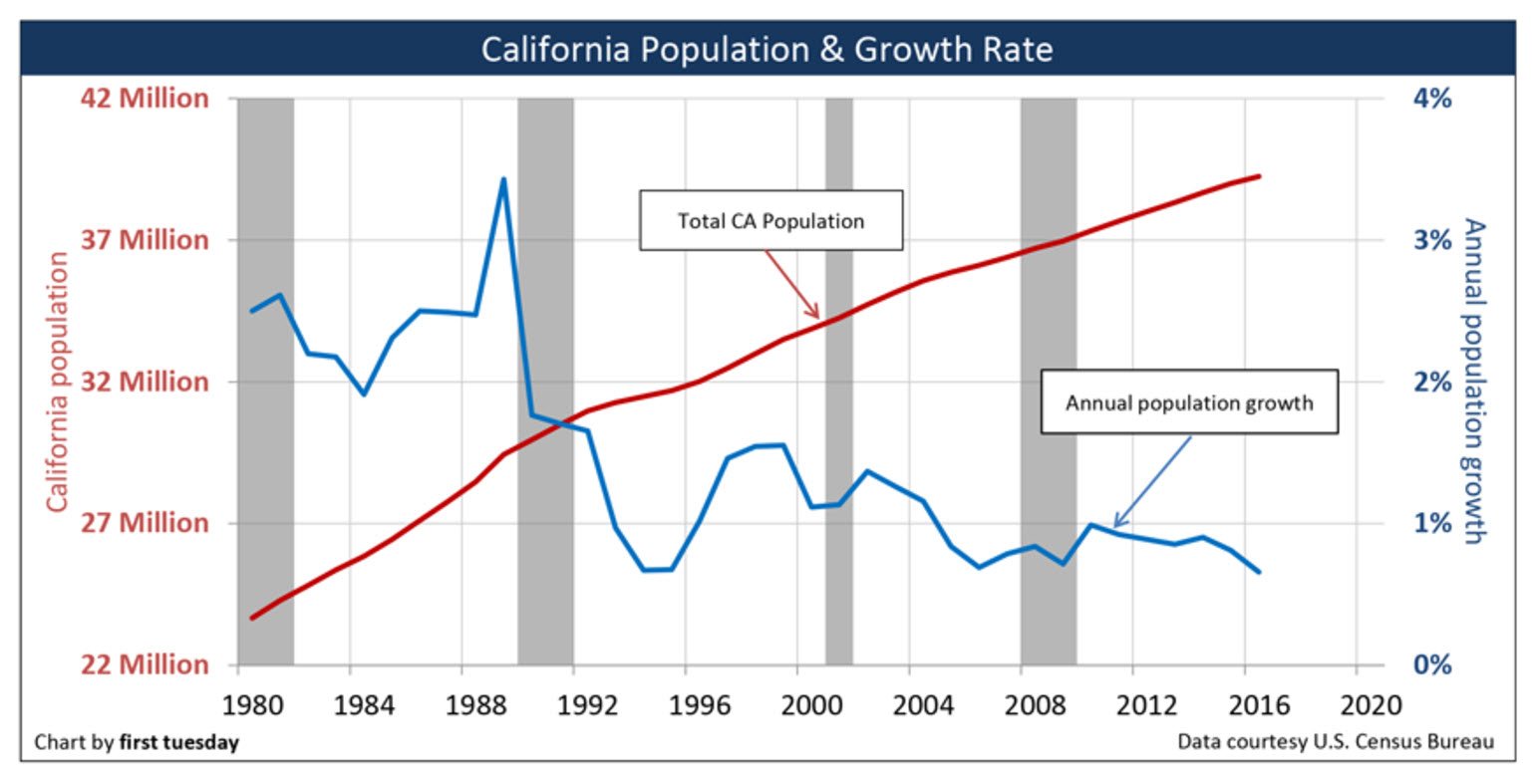

So here is a chart showing California's population growth as well as the annual growth percentage.

Notice something curious: annual growth rates have been declining for some time. In fact, annual population growth was fastest in the late 1980's. California's population has been growing by less than 1% a year for more than a decade. Just to be clear: 1% annual growth is pretty modest and manageable.

So what was happening with home prices back in the 1980's during that population boom? Well, they were going up, but nothing remotely like the bubble between 2001 and 2008, a period of time when population growth was slowing. With the housing recovery (aka: Bubble 2.0) we see the same thing: double digit housing price increases despite population growth well below 1%.

I'm trying here to dissuade you of the notion that this is a simple supply/demand problem because it seems to be the only thing Democrats and Republicans in California can agree upon. By their consensus, this is a problem of not having enough housing and, thus, what is needed is to merely build more. From the CalWatchdog.com article:

But while there’s broad agreement that housing affordability is in crisis, there are two schools of thought on how to address it. Democrats are primarily trying to raise taxes and fees to pay for more government-subsidized affordable housing, whereas Republicans want the state to chip away at local governmental barriers to home construction.

Democrats, who control the government in California, have all kinds of proposals for subsidizing housing:

Their high-priority measure, when legislators return to the Capitol late next month, is Senate Bill 2, which would impose fees of $75 to $225 on every real-estate transaction to provide $225 million in annual funding to subsidize developers of low-income housing.

“With a sustainable source of funding in place, more affordable housing developers will take on the risk that comes with development and, in the process, create a reliable pipeline of well-paying construction jobs,” according to the Senate bill analysis.

What is $225 million in the context of California's housing market? The real estate journal First Tuesday reports that, in 2016, there were 49,400 single family homes and 51,200 multi-family units constructed. A $225 million "sustainable source of funding" would amount to a little more than $2,200 per unit.

Let's say we focused that money to subsidize 5% of the new units being constructed, a total of 5,030 new affordable units each year, and we assumed that the entire fund went to the subsidy (no bureaucratic overhead). We'd then be able to reduce the cost of a unit by $45,000; this in a state where the median single family home price is $516,000.

To put this another way, the subsidy -- again, assuming no bureaucratic overhead -- would take $190 per month off of a $2,170 per month mortgage, assuming a down payment of $51,000 on the median home. For comparison, a 1% increase in interest rates would add $270 per month to the same mortgage. (In reality, a 1% increase in interest rates would lower home prices because buyers could purchase less home for the payment they can -- or can't -- afford.)

In short, if the goal is to subsidize our way out of this mess, Senate Bill 2 isn't going to make a dent. San Diego columnist Dan McSwain perfectly described the outcome of such a policy:

Kafka could hardly design a better shortage-inducing system: Raise the overall price of market units, thus ensuring that fewer get built, in order to subsidize a handful of poor families — having been rendered unable to afford the pricey units — who win a lottery administered by local government agencies, with staffs funded by housing fees that inflate prices.

Senate Bill 2 would -- if approved by voters -- authorize the state to borrow $3 billion to build low income housing (along with transit-oriented housing) because it's not like California should have any concerns over high debt levels.

Then there is Senate Bill 35. Proposed by Senator Scott Wiener, it doesn't "chip away at local government barriers to home construction," unless your idea of a chipper comes from the movie Fargo. The bill reportedly:

“creates a streamlined, ministerial approval process for development proponents of multi-family housing if the development meets specified requirements and the local government in which the development is located has not produced enough housing units to meet its regional housing needs assessment,” according to the bill summary. The streamlined process would apply where a project meets “objective zoning, affordability, and environmental criteria, and if the projects meet rigorous labor standards,” according to Wiener.

That's a rather benign way of saying that, if the state approves of your development, they will override local approval processes. Such legislation is always the last resort for tragically brittle systems. Layer upon layer of regulation and protection is put in place until the system comes grinding to a halt. The only way around it is the strong man tactic. The acceptability of this approach usually depends on whether or not it is your chosen strong man (or woman) who wields power. Californians supporting Senate Bill 35 might be less enamored if it were the right-leaning U.S. Senate instead of the left-leaning State Senate ramming approvals down people's throats.

The CalWatchdog.com article only detailed Democrat proposals since only Democratic proposals matter in the state of California.

Let me sympathize with California Republicans because I agree with the simple logic that supply and demand equilibrate at a price. If that price is too high, then reduce demand or increase supply and the price will come down.

Those who attempt to deny that truth on one hand while pumping potentially billions of subsidies into the housing market on the other hand are all kinds of incoherent to me.

Yet, I'm not satisfied that this is merely a supply problem. By my calculations, California added around 230,000 people last year while they built a little over 100,000 housing units. That's one unit per 2.3 people, below the 2.9 state average reported in the 2010 census. How is price spiking so drastically if supply is keeping up with demand?

Here's what is clear to me, and I believe the numbers bear this out: California has created one of the most volatile housing markets in the country. It seems to exaggerate upswings and then overcorrect during downturns. It's a boom/bust state.

I see continuing efforts in California to both create booms and then mitigate busts. In classic left/right economic stereotypes, left-of-center Californians seem very comfortable with the boom but have a lot of despair with the bust. In the words of Tomas Sedlacek, they are manic-depressive but do not want to treat the mania, only the depression. It doesn't work that way.

Prop 13 -- the infamous referendum to stabilize property tax (protect citizens from the pain of the manic phase) -- has fueled across-the-board demand for new housing units, from local governments starved for tax revenue to stagnant housing markets that don't turn over as much as they otherwise should. This has justified all kinds of bizarre transportation investments and equally bizarre commuting patterns.

These in turn have placed an even greater premium on location and further exaggerated winners and losers. Throw in Federal Reserve meddling with the price of money so as to re-inflate the housing/banking/stock market bubbles and the fact that California is on the receiving end of tech bubble money, and you have a really fragile and volatile situation, one where complex and interrelated systems can quickly become unhinged.

I love California but, as I've said before, I would not buy a house there today any more than I would buy Amazon with a PE Ratio over 200. Lots of people think these are good investments and, looking backward, they can make a strong case. I'm not one of them.

For those of you wondering what I would do -- would I subsidize housing or chip away at barriers -- I'm going to go back to the recommendations I made last month in "A Composition of Fallacy." What California needs most is real price signals and true feedback:

- Provide, by right, the ability of every property in the entire city to be improved to the next level of intensity.

- In places where dramatic leaps in development intensity have been codified, downzone to allow only the next level of intensity.

- Halt the expansion of all infrastructure systems that are meant to support additional development until such time (likely never) that the tax base is sufficient to cover the ongoing maintenance and replacement of all existing infrastructure systems.

I think it is only a matter of time before California finds itself in another bust cycle, where the emergency of rising prices gives way to the catastrophe of falling prices, where the manic cycle ends and the depressive cycle begins. It doesn't have to be this way. California could decide to become a state where it allows its cities to grow into strong towns.

---

Edit Note: After outrage by a number of you, I made one small change to this post. I changed, "Yet, I'm not satisfied that this is a supply problem," to say, "Yet, I'm not satisfied that this is merely a supply problem." The addition of the word "merely" creates the proper emphasis in a sentence that was widely-quoted, an emphasis that is contained in context of the article (though not as tweetable).

You wake up with a sore back. Do you have a back pain problem or do you have combination of poor mattress, bad pillow, poor posture, aging and lack of exercise problem? To me, back pain would be the symptom of the problem, but to many who find themselves in a day-to-day battle-to-the-death with the forces who resist changes to the bed, pillow, etc... back pain IS the problem. To those in that position, go and fight your back pain. We're going to work on the underlying causes here. Don't mind us.

(Top photo by rbotman01)

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.