Dispatches from Spokane: Living a Soft Default

Spencer Gardner is a Strong Towns member and regular contributor who recently moved to Spokane, Washington. This is his second in a series of posts about relocating to his new hometown of Spokane, WA. You can read Part 1 here.

When my family and I moved to Spokane earlier this year, we were surprised by a lot of things, good and bad. One thing that didn’t surprise us was the poor condition of the roads. Spokane roads are famously bad, so bad that it came up several times in conversations with people who learned we were moving there. So bad that news outlets run stories informing readers how to apply for damage claims. So bad that you could literally watch an hour or more of YouTube videos about the potholes here.

I realize our previous article in this series glossed over the post-war period in Spokane. These years obviously play a part in Spokane’s story, but compared to the early years, the pace of urban change was much less extreme. In fact, the stark difference between pre-war and post-war Spokane may have something to do with the aforementioned pothole problem.

Click to view larger

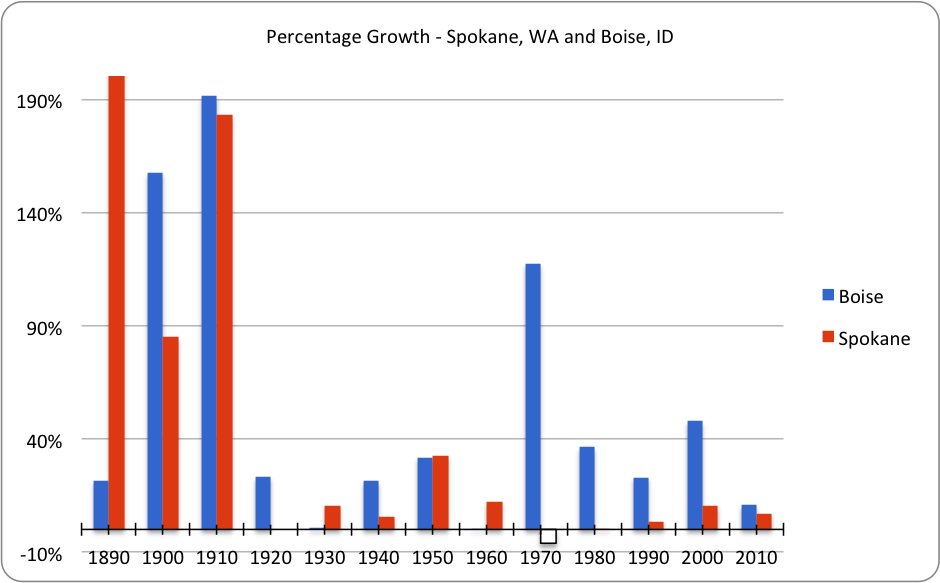

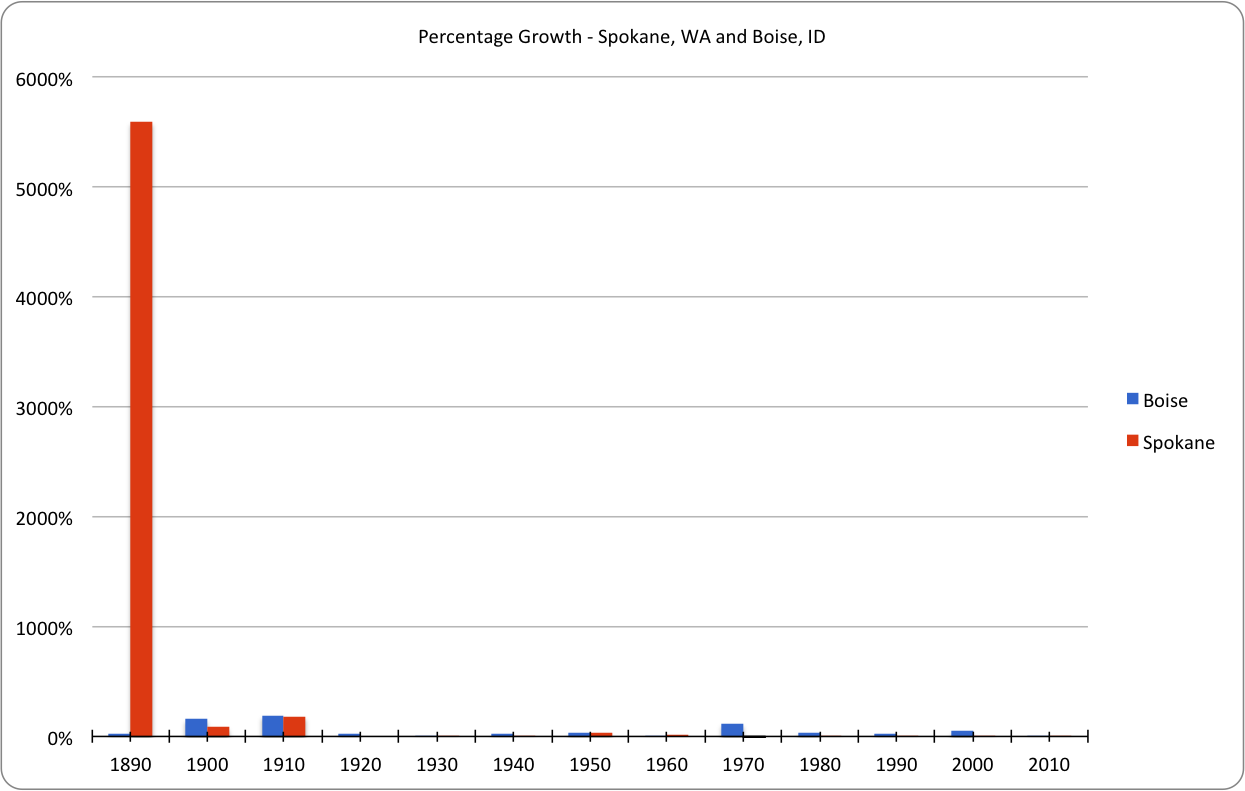

Let’s compare Spokane’s population with that of Boise, the state capital of Idaho. Boise and Spokane are pretty close geographically (by Western US standards) and have almost the same population; however, Boise is a much more typical Western boomtown. Notice the post-war trend in the population chart. By 1960, Spokane’s meteoric rise had flattened, and the population even dipped slightly, followed by moderate growth through the turn of the millennium. Boise, on the other hand, remained a small town until the 1960s, when the population began to soar. The city has seen double-digit growth each decade since, as illustrated in the chart showing percentage growth.

And just to illustrate how incredible Spokane’s early growth was, note that its percentage growth from 1880-1890 is literally off the chart at over 5,000%. I’ve included a re-scaled second chart to make the magnitude clear. Yes, it was starting from a small base, but that’s still an incredible amount of growth. Recall that a child born in Spokane in the 1880s would have started life in an isolated village of less than a thousand people and entered adulthood in a metropolis approaching 100,000.

Remember the central dynamic of the Growth Ponzi Scheme: in the short term, new growth provides a quick infusion of cash at relatively low cost. In cities like Boise, the costs associated with replacing the second and third life cycles of infrastructure supporting less-productive development from the late pre-war and early post-war period have been masked by the cash infusion that comes from continued new growth. In Spokane, however, the growth evaporated. The next wave of population needed to keep up appearances never came, certainly not at the levels needed to cover the massive liabilities from earlier decades. This offers a clue as to why roads here are in such bad shape: the money to fix them didn’t show up.

The years following the growth period were less than kind to Spokane for more issues than the quality of roads. For decades it has endured a certain reputation. To be fair, I find Spokane to be lively, charming, and full of promise, as does The Stranger, Seattle’s alternative bi-weekly newspaper. The malaise brought on by low growth seems to have suffused the entire city, affecting more than just the municipal budget. Once a growing city has lost its mojo, it’s exceedingly hard to get it back.

Spokane is an excellent illustration of what we call a “soft default”. Like virtually every other city in the US, it is functionally insolvent, but as critics and friends alike point out, functional insolvency rarely results in legal bankruptcy. Spokane has never declared bankruptcy. On the contrary, its bond rating is quite good. The explanation for this is simple: cities have a contractual obligation to repay their monetary debt, but there is no such contractual obligation for infrastructure maintenance, capital improvements, or municipal operations—these are seen as political issues. So in the case of Spokane, creditors are more than happy to continue loaning the city money. They know that crumbling roads stand behind debt service in the line for cash from the city’s coffers. Likewise, politicians can simply point to lack of funding when angry constituents demand better services.

To be clear, Spokane isn’t the only city with potholes, and it’s not the only city with budget troubles. The potholes themselves are merely an emblem of deeper structural issues related to how cities across North America have grown for the better part of the last century. Spokane has had to face some hard realities due to the abrupt end of growth, and anyone familiar will tell you it has suffered through the ensuing withdrawal symptoms. The Boises of the world are still riding the high, but exponential growth can’t last forever. The comedown will happen sooner or later.

Chuck is fond of saying that Detroit isn’t an outlier, it just got there before the rest of us. The truth is, bankruptcy is uncommon at present and it may even remain so in the future, but the relentless mathematics at work in the Growth Ponzi Scheme apply universally. Your city may avoid the extremity of Detroit’s fate, but chances are it’s already experiencing a soft default. And if your city is riding high in the growth phase of the Ponzi Scheme, remember that Spokane was there too, a long time ago. We’re not an outlier, we just got here first.

In our next installments we’ll evaluate the productivity of different parts of the city, meet some people working to make their neighborhoods stronger, and hopefully chart a path forward to make Spokane a stronger town.

There’s a certain artistic quality to abandoned spaces—but if we look a bit deeper, these ruins also hold lessons about patterns of disinvestment and policy shifts that have adversely affected American communities.