Safety For Whom?

Michael and Jennifer Smith are Strong Towns members who live in Rockford, Illinois. We have previously featured their inspiring work to make Rockford a stronger town. Today we share Michael Smith's original research on pedestrian safety in Rockford, which he recently presented to local elected officials. It was originally published at the couple’s blog CitySmiths.

If you were to close your eyes and place a finger on any transportation-related document your city is producing, there’s a good chance you’d land on one word: "Safety."

Excerpt from Rockford's Complete Streets Policy

If you read recent resolutions and agreements that the Rockford City Council has adopted, you'll find all the right words are there: “multimodal”, “all ages and abilities”, “safe routes to school”, even “maximize carbon-free mobility”. All good.

Recently, I've been thinking about how this municipal value—safety—aligns with our city's existing conditions of pedestrian mobility. I began with the following questions:

How "safe" are pedestrians;

What areas are less safe than others for pedestrians; and

How can we work together to maximize safety and accessibility for non-motorized users of our transportation network?

Every so often I would hear of pedestrians getting hit by drivers on certain roads. So I began to research our library’s newspaper archive. Turns out we’ve had a problem with pedestrian collisions for some time. An article in the Rockford Register Star describes the treacherous conditions on a local thoroughfare, Alpine Road:

What used to be a comfortable country road has become one of the major links between the north and south portions of the city...Almost 40 accidents between Charles Street and Highcrest Road had occurred in less than three months. Last April the speed limit on Alpine was reduced to 45 miles per hour north of Spring Creek Road...But two pedestrian deaths in the last month indicate that safety is far from achieved. Pedestrian safety can be enhanced if sidewalks are available...Children, in particular, often walk on curbs or on lawns to get to their schools.

The date of the above text? January 1974. Over forty years ago.

Eventually it was time to pair qualitative research with quantitative research. I began with the following hypothesis:

Pedestrian collisions occur more frequently on principal arterial roads in the City of Rockford.

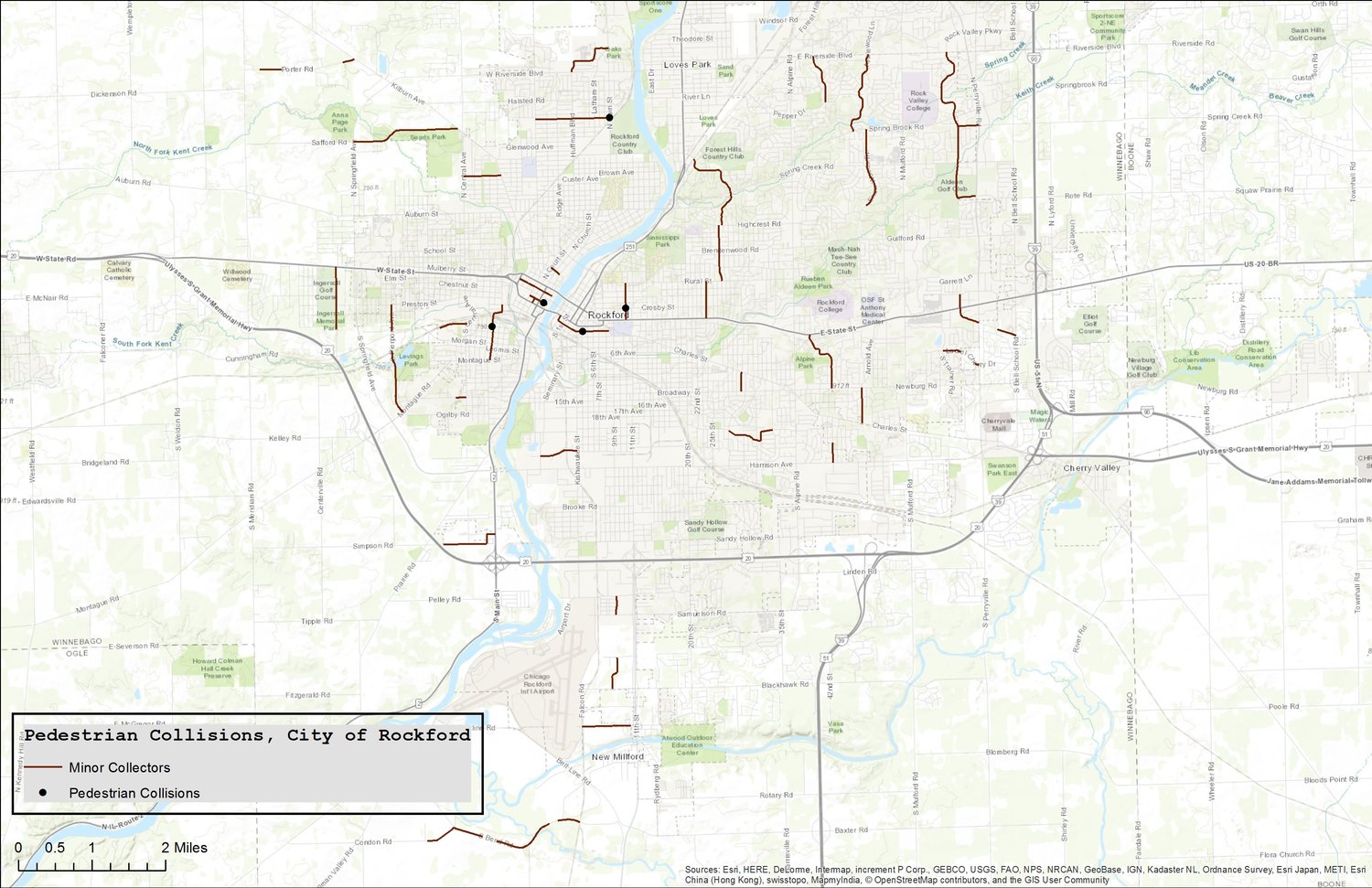

So I obtained ten years of data from the Illinois Department of Transportation. Merging the data sets together, I found that from 2006-2015, 551 pedestrians were hit by the driver of a vehicle in the City of Rockford. I made this map to plot the locations of these crashes:

Of the 551 collisions, 23 were fatal. (Note: It is likely that these fatalities occurred at the scene. It is unlikely that IDOT has obtained data from area hospitals, so the number of fatalities may be higher). I found that 56% of collisions happened in the daytime, not at nighttime (when people are often blamed for not wearing reflective, bright-colored clothing). I also found that inclement weather—snow, rain, fog, and wind combined—was present in only 18% of the collisions. It is clear that these environmental factors, which are often blamed for crashes, do not tell nearly the whole story.

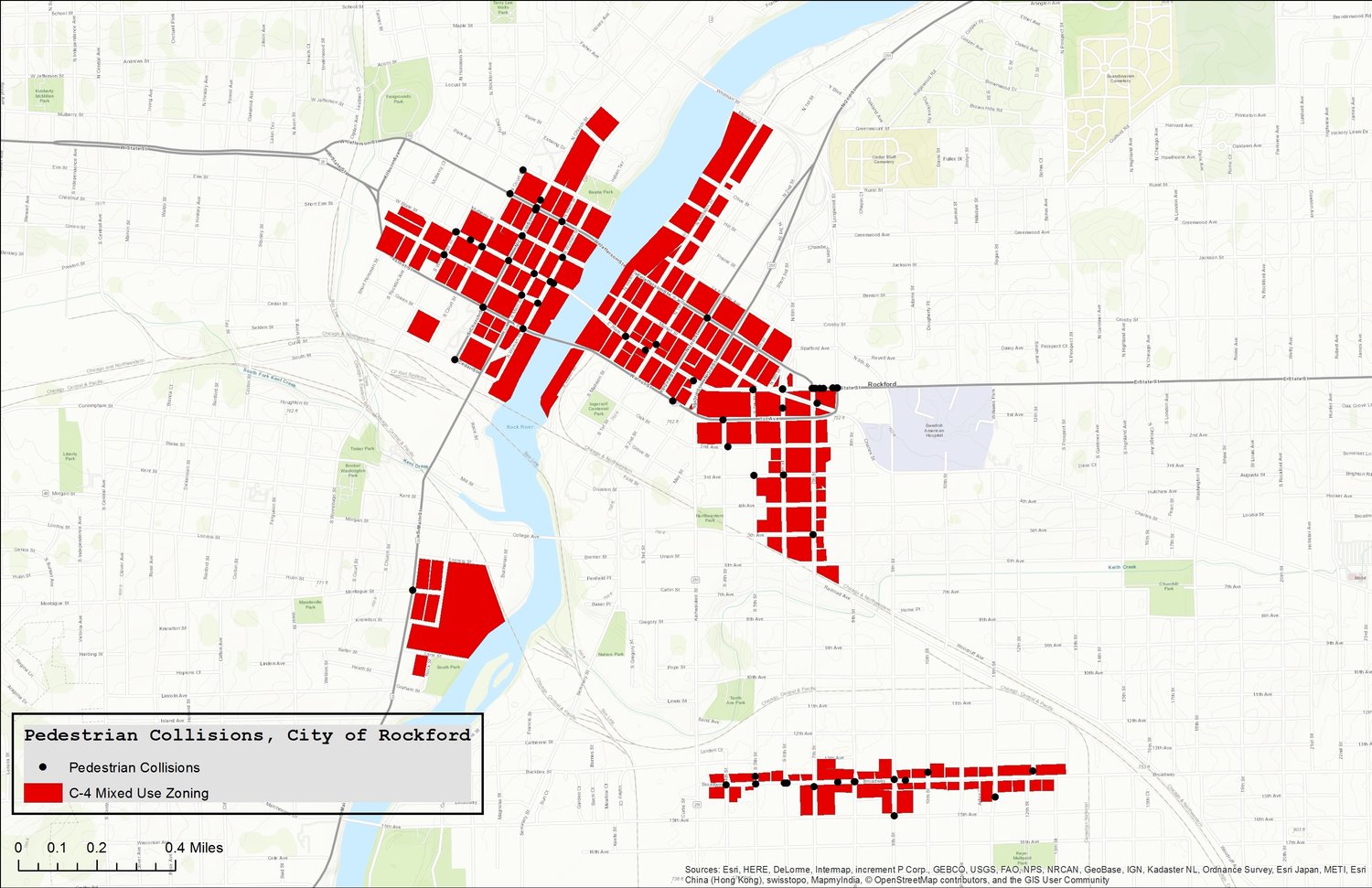

Pedestrian collisions in areas with mixed-use zoning in Rockford, Illinois.

I then overlaid zoning districts onto the collisions. Our C-4 zoning designation represents the downtown mixed-use district. It is the most compact, walkable space we have in Rockford. With events like City Market, Friday Night Flix, and Stroll on State, we have a lot of people out walking downtown. Surely most of our collisions are happening in this district? Actually, no. While not insignificant, only 15% of all pedestrian collisions occurred here.

Pedestrian collisions in areas with C-1 and C-2 (commercial) zoning in Rockford, Illinois.

On the other hand, let's examine a couple of our commercial districts. This is where most folks are getting their groceries, cashing their checks, or dining out. 33% of all pedestrian collisions occurred here. So what is it about these districts? More particularly, what does the type of roadway bisecting these zones tell us about pedestrian collisions?

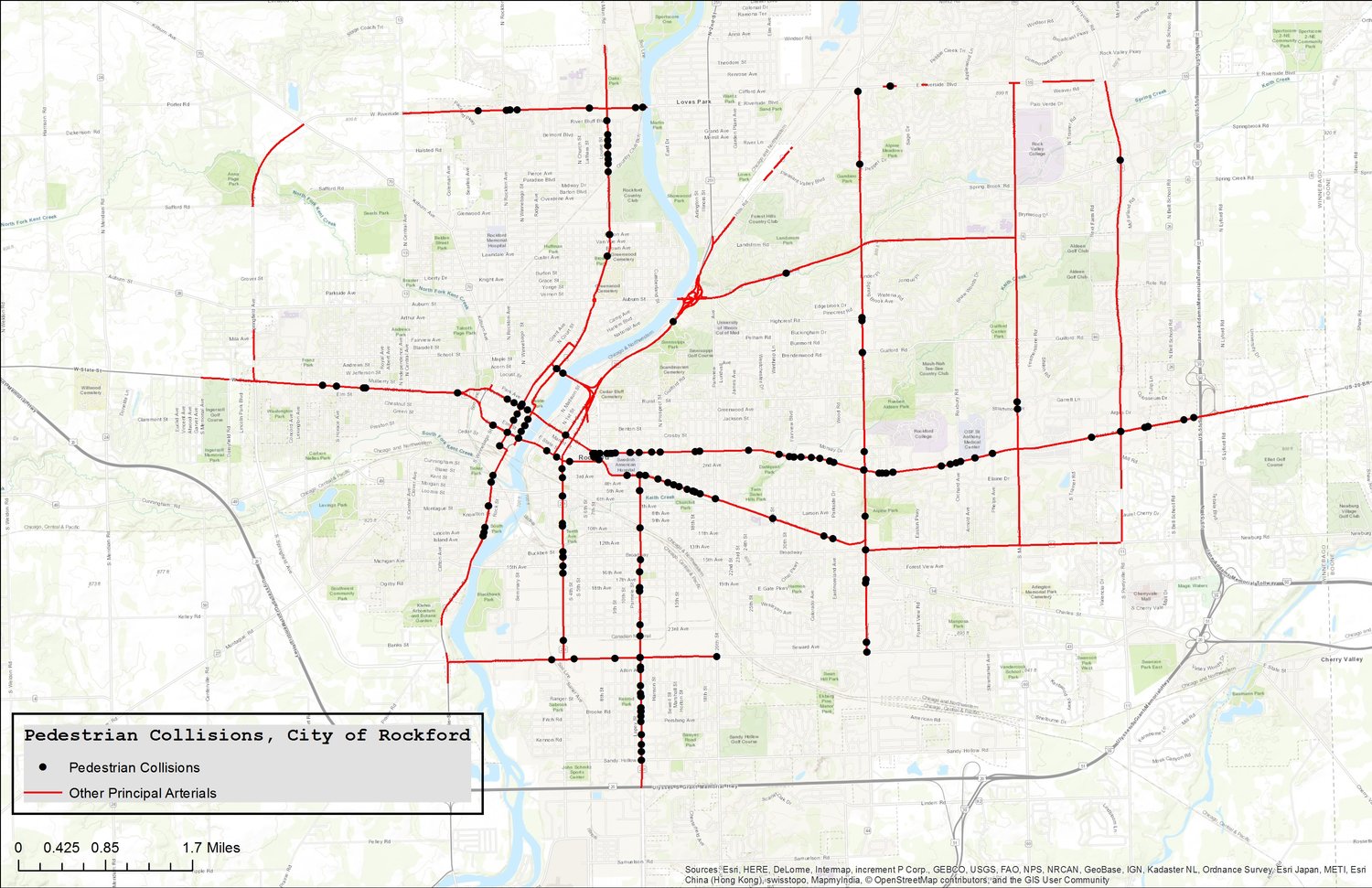

The city and our regional MPO (Metropolitan Planning Organization) have classified our roadways with seven designations ranging from "local streets" to "interstate." Examining collisions by roadway classification overwhelmingly confirmed my hypothesis. From 2006-2015, 81% of all collisions in Rockford—446 out of 551—occurred on principal arterial roads. Only three roads accounted for 2 out of every 5 crashes:

23% of all collisions (126 of 551) occured on State Street, which is owned by IDOT, the state department of transportation.

9% of all collisions (46 of 551) occurred on 11th Street.

8% of all collisions (39 of 551) occurred on Charles Street.

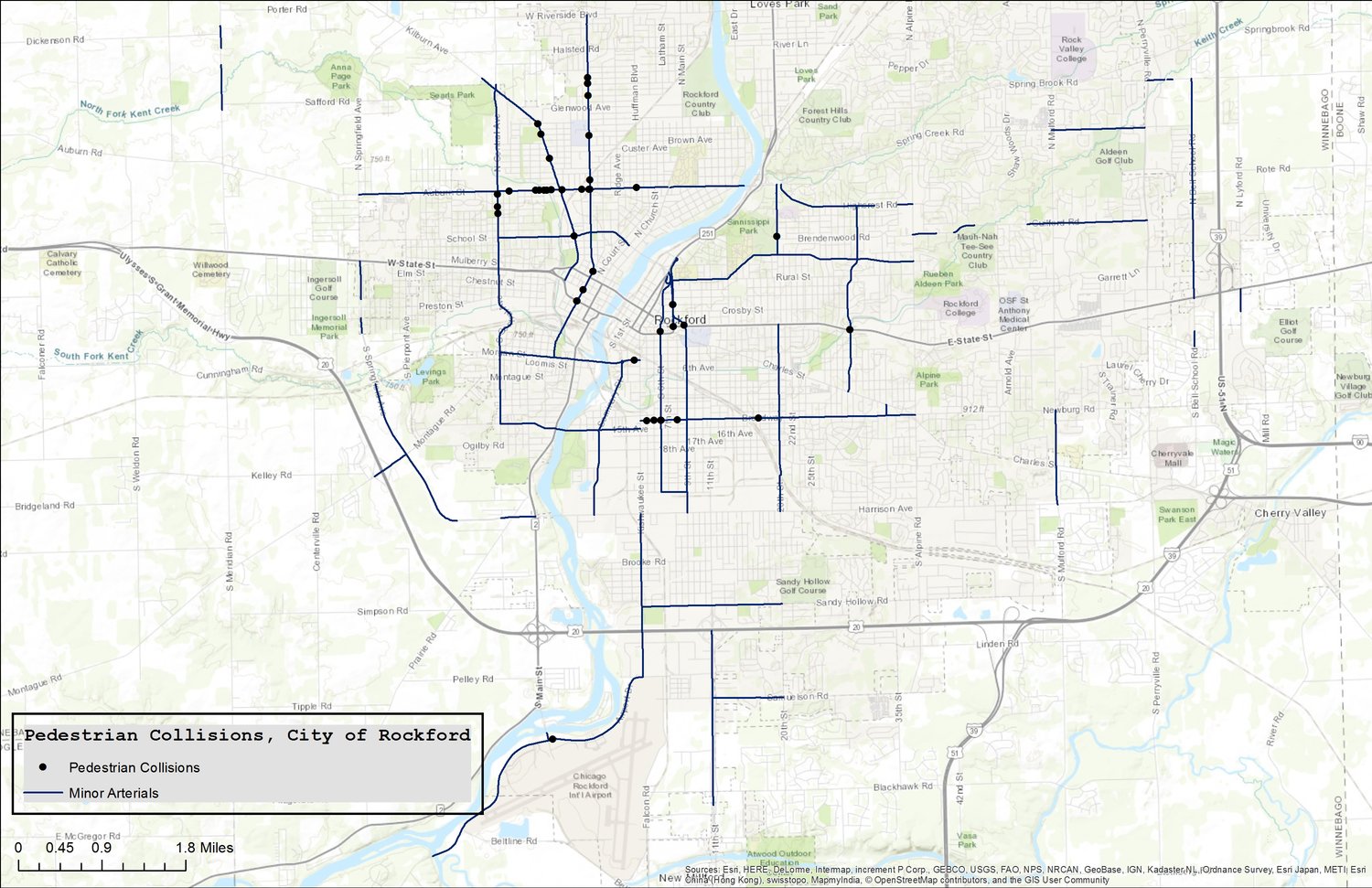

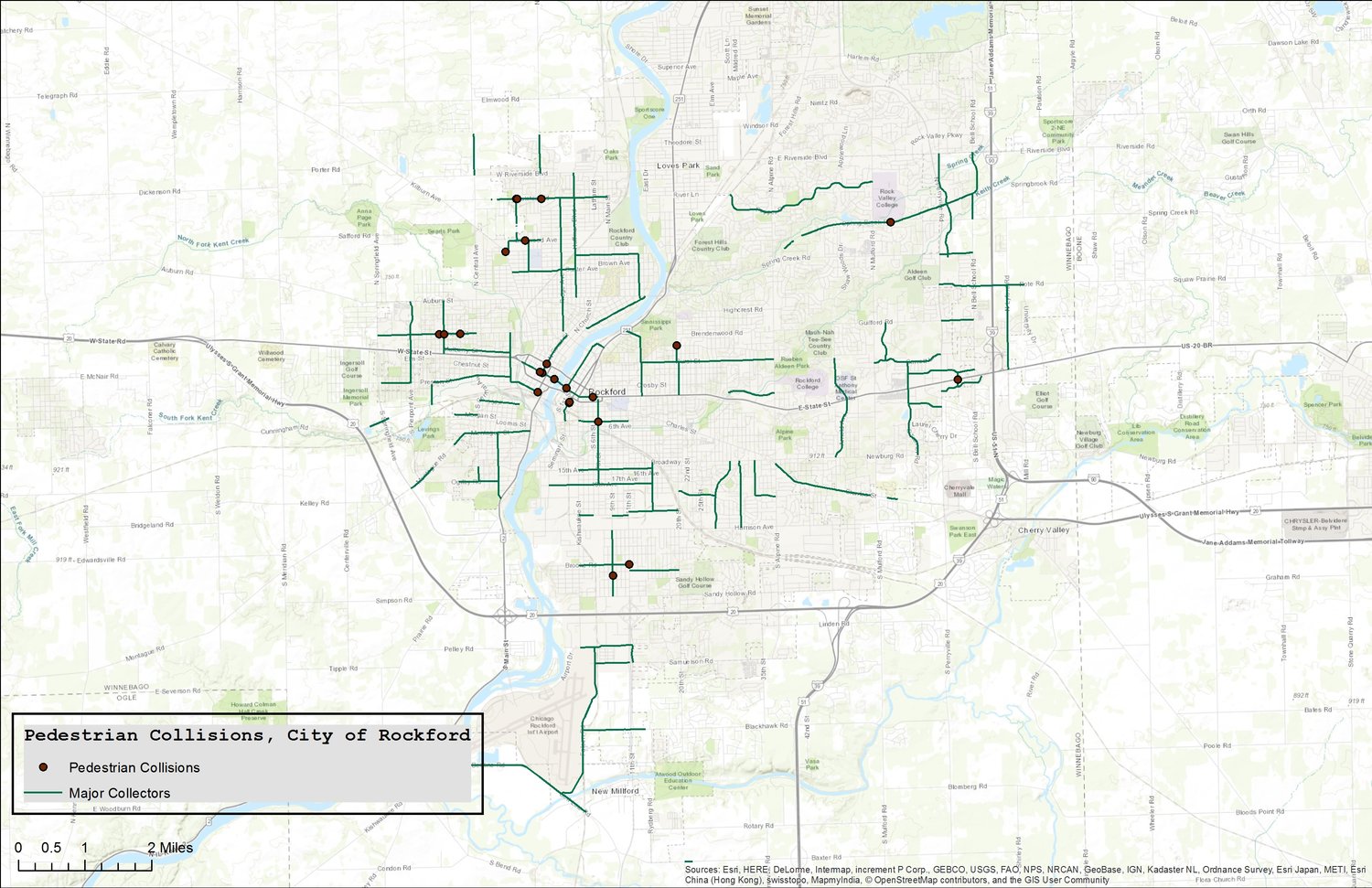

This slide show allows you to compare the maps of pedestrian collisions on four different roadway classifications:

Principal arterials do a great job at moving a large number of vehicles every day. However, they do a poor job at moving—and protecting—pedestrians. This is a direct result of the design characteristics typifying arterial roads, which frustrate pedestrian mobility and compromise pedestrian safety.

Safety For Whom?

How has safety been used to alter or maintain asymmetric relations of power? This is not just a question of who gets to drive and with how much latitude, as if the equation is simply car = freedom = equality. Auto-mobility and the freedom it promises needs to be understood as an obligation as well. The system of auto-mobility in the US in many ways demands that one must drive a car. The disciplining of mobility organized through traffic safety is thus a means of keeping the system running smoothly, even as if often works as a means of keeping systems of social inequality intact.

-Jeremy Packer, ‘Mobility Without Mayhem’

Regular Strong Towns readers are keenly aware of the design features of principal arterial roads, which are almost always synonymous with “Stroads." These arterials serve high-speed traffic with multiple wide, highway-like driving lanes in each direction. But then they put that traffic in environments with a lot of intersections, turning vehicles, adjoining businesses, and people on foot. The result is extremely unsafe conditions.

Recent reconstruction of principal arterials in Rockford has failed to remedy these dangerous "stroad" conditions:

South Main Street, looking north from Morgan Street. IDOT recently completed this roadway project which includes four 12' travel lanes. 12' lanes are wide, especially given that this stretch is in a compact, walkable area of our city and is less than one mile from city center.

During the South Main reconstruction project, IDOT removed the on-street parking and demolished a tax-producing building so drivers could have ample parking.

Jefferson Street looking west towards our downtown. We’ve given drivers an oversupply of travel lanes—four lanes on the bridge—while the annual average daily traffic (AADT) ranges only 6,000-8,000 cars a day, a level that could easily be accommodated with two lanes. This wide open roadway communicates to the driver an environment that is frictionless, and an illusion of safety that encourages high speeds.

Above and beyond pedestrian crashes, there have been 153 vehicle crashes on Jefferson Street in ten years. Here’s what happens when speeding vehicles meet a compact urban environment with minimal setbacks:

Stroads are fundamentally unsafe environments for people on foot. That is borne out by the fact that they have been the setting for 81% of all pedestrian collisions in Rockford, even though they are not environments that encourage walking in the first place.

I believe that engineering at the municipal level can play a significant role in reducing speed and improving pedestrian safety. So I’ve met with Mayor Tom McNamara to present my findings and discuss the administrative implications from the research.

My emphasis is on reducing vehicle speed, as I believe that is the most significant variable at play. Speed increases risk, reduces recognition, and extends the stop distance of vehicles. Reducing speed gives pedestrians a fighting chance in the event of a collision.

Additionally, I hope that the construction of basic pedestrian infrastructure is one of the fruits of this research. There are several portions of State Street, for example, that lack sidewalks, bus platforms, etc. and have sustained a high proportion of pedestrian collisions.

Dirt tracks alongside the roadway indicate that people walk here despite the absence of a sidewalk. You can imagine how difficult this gets for people who walk in the winter.

In addition to meeting with the mayor, I'm in the process of meeting with select council members to discuss the findings. Thus far, I’ve met with one alderman, and plan on meeting with two more. Together, 53% of all collisions happen in their wards.

My next steps have not fully materialized yet, but they will involve focusing on a section of 11th Street, gathering data on pedestrian and motorist behavior, and preparing a municipal plan for addressing this issue. Although this is my final project for graduate school, I hope that the recommendations will be considered by city officials.

I’ve been presenting my findings to friends and residents as well. We all have a stake in ensuring our transportation network really lives up to the aims we espouse in our municipal documents—chiefly among those safety.

Here are a few things you can consider in your own community:

1. Have a roadway improvement in your neighborhood? If you’re like Rockford and have a Complete Streets policy in the books, then that policy probably has some performance measures to ascertain success. For example: Linear feet of sidewalk or bike lanes, or rate of children walking to school. Ask your council member: "How is our ward contributing toward that end?"

2. Long before the dump trucks arrive, get familiar with your community’s Capital Improvement Plan. Unless you're in a super-amazing place like Seville, most active transportation improvements probably take a long time. Look ahead, see what the city has planned for the next five years, and make sure your council member knows that you support safe roadways that slow vehicle speeds and improve pedestrian mobility.

3. Insist on adequate accommodations during construction. Every time you see one of these signs—“Sidewalk Closed”—ask yourself, “What’s the Plan B?” If the sidewalk is closed for a construction project, the city is required to provide an alternative. Given our incomplete sidewalk network, I think it’s important that we fight to keep what we have connected.

4. A final thing to do: Be careful.

For those who walk in Rockford: I hope this research shows you the roads that are most unsafe to walk near. For those who drive in Rockford: Be mindful that there are other people that cannot or choose not to use a motor vehicle for their mobility needs.

The conversion of roads to stroads in the automobile era has dramatically affected pedestrian safety in Rockford and countless other cities. We have a long road ahead of us in reversing the harm that prioritizing vehicle speed and forgiving design has wrought. I earnestly hope the next forty years are better for non-motorized users of our transportation network.

(Photos and graphics by the author unless otherwise indicated.)

Michael and Jennifer Smith enjoy learning about and applying the principles of new urbanism in their community, working to promote the value of and preserve historic places in Rockford, and finding ways to ensure that every person who calls Rockford home can experience all the best that a city has to offer. They blog at CitySmiths.