Niagara’s Fall and Asheville’s Unlikely Rise

This is the second article in a two-part series about urban renewal. Read Part One here.

“Tourism does not go to a city that has lost its soul.”

One hundred years ago, Asheville, North Carolina and Niagara Falls, New York were quite similar: Tourist-centric boomtowns that attracted visitors from their entire regions for their natural amenities, but kept people interested with their urban charms.

When the Depression hit, their paths diverged: Asheville boarded up its windows while Niagara Falls revved up its bulldozers. In hindsight, a comparison of the two cities provides a reflection of the legacy of urban renewal.

Asheville and Niagara Falls each began humbly, but underwent explosive growth in the late 19th century. Asheville became connected to the rest of the state via railway and soon established a strong economy built on tourism, trains, and tuberculosis sanitariums. Around the same time, Niagara Falls was booming in its own right. The city’s signature geographic feature made it desirable as a tourist destination, but it also benefited from another economic engine: the energy harnessed from the rushing water of the Falls. Both cities were trending upward.

Asheville's Debt: A Blessing in Disguise

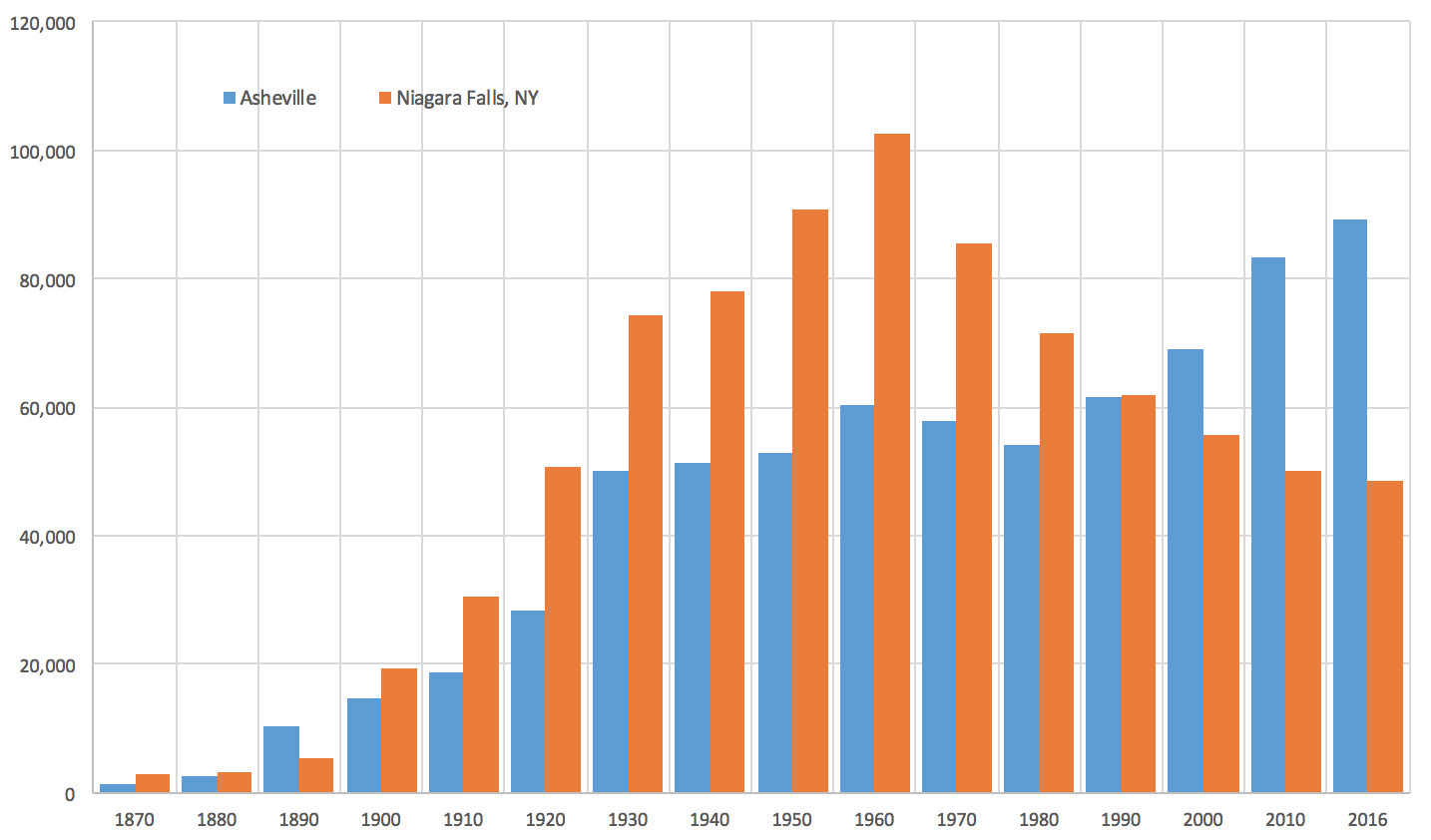

But then Asheville’s fortunes changed. During an audit in 1929, the city discovered that they had $18,000 in their bank account, not the $5 million that they thought they possessed. The Great Depression was made even Greater, and the population stagnated for 60 years.

Asheville had one of the highest debt per capita ratios in the country, but it stubbornly and slowly paid the debt off instead of relying on federal money. In the following decades, highways bordering the city funneled consumers away from downtown and toward the new mall, but there was not enough capital or interest to tear down its numerous traditional buildings. By the late 1970s, much of downtown Asheville consisted of boarded-up shops along empty streets, yet it retained its traditional urban form. In paying off its debt, Asheville had unintentionally preserved its greatest assets: its historic buildings.

While cities across the country were demolishing swaths of their mid-rise buildings on gridded street networks, Asheville sat out urban renewal almost entirely.

Niagara's Windfall: A Dangerous Gamble

Niagara Falls, on the other hand, was one of the first cities to embrace urban renewal policies.

This interactive map visualizes the contrast in block size and land use in downtown Niagara Falls from 1934 to 2017. Slide the bar to the left and right to compare the city in 1934 to its 2017 layout.

After the Depression, Niagara Falls recovered quickly, reaching a peak population of 102,000 in 1965. The city was primed for perennial success, and city officials were eager to build the city around the automobile.

Niagara Falls was inundated with “cataclysmic money”—a term coined by Jane Jacobs referring to large influxes of capital under the control of large actors. At its zenith of success, Niagara Falls received checks from Washington and Albany amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars all at once. This type of windfall typically encourages large institutions to make orderly but dumb decisions, rather than employing the careful thinking and testing that comes from having a small amount of money at your disposal (what we call “chaotic but smart"). It’s similar to the experience of lottery winners who mismanage their winnings and end up worse off than before they ever played the game.

The Niagara Falls Mill District. (Source: John Guthrie.)

The city took a big gamble. They tore down many of their historic neighborhoods in the hopes of attracting development projects that would revitalize those areas. But, unluckily for Niagara Falls, that rebuilding never happened. There were grandiose plans, but most of the land ended up only as parking lots. The gamble didn’t pay off, and the future looked bleak. In effect, the city had demolished decades of productive growth—a development pattern it might never be able to reconstruct.

My colleague Josh McCarty at Urban3 uses a helpful football analogy: “Niagara Falls was doing pretty well, until they were down by three points. Then they panicked and started throwing a Hail Mary on every play. Now they’re deep in the hole, and they realize they should have been aiming for first downs the whole time. Instead of big-budget silver bullet solutions, cities should work to revitalize incrementally.”

An Alternate Path for Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls’ tragedy is even greater when the spectacle of its waterfalls is taken into account. Geographically speaking, Niagara Falls should be one of the most interesting and attractive cities in the country. So let’s take a minute to envision an alternate reality: If historic Niagara Falls hadn’t been razed and left to crumble, what would its blocks of fine-grained urbanism be worth today, both financially and as a cultural destination?

Josh points out the redevelopment potential for properties along the Niagara Gorge in the Mill District. He wonders how much a Wall Street millionaire would pay for a falls-view loft if these buildings were restored. What kind of value could that generate for the city?

On the Canadian side, several hotels charge an average of $200 more per night for rooms with a view of the falls compared with those that lack a view. It doesn’t take an economics degree to guess how incredibly valuable this sort of redevelopment would be for the town of Niagara Falls.

An Alternate Path for Asheville

On the other hand, what if Asheville had gotten the Niagara Falls treatment? If it hadn't been so indebted, it might not have sat out urban renewal and it might have experienced the destruction of its most valuable assets. Sure, tourists would still visit the Biltmore Estate and drive down the Blue Ridge Parkway, but the city would be unremarkable and look just like every other mountain town.

It can be hard to grasp the the whole legacy of urban renewal, in part because its scope is so large that we can only try to imagine what would have happened without it. But with the benefit of retrospect, the comparison of Asheville and Niagara Falls offers a sort of rough double-blind experiment in its long-term effects: Take two cities, both with a natural amenity and a similar population size. Keep most of the historic buildings in one, and tear down almost all historic buildings in the other. In the course of history, the results differed from what anyone could have expected.

Populations of Asheville and Niagara Falls over time. (Source: Urban3)

Asheville’s debt crisis ended up being a blessing in disguise, and Niagara Falls’ great wealth turned into its greatest liability. It’s another exhibit in the continuing case demonstrating how destructive urban renewal was for our cities.

Cover image: Niagara Falls before urban renewal. Source: The Library of Congress.

This small town is considering overhauling its main street to embrace walkability and good old-fashioned main street urbanism.