A LOSing Proposition

In cities throughout America, traffic studies are conducted to determine the Level of Service (LOS) for cars. This scientific-sounding metric basically looks at the busiest 15 minutes of the busiest hour of the day, and determines how well auto traffic flows through a given intersection.

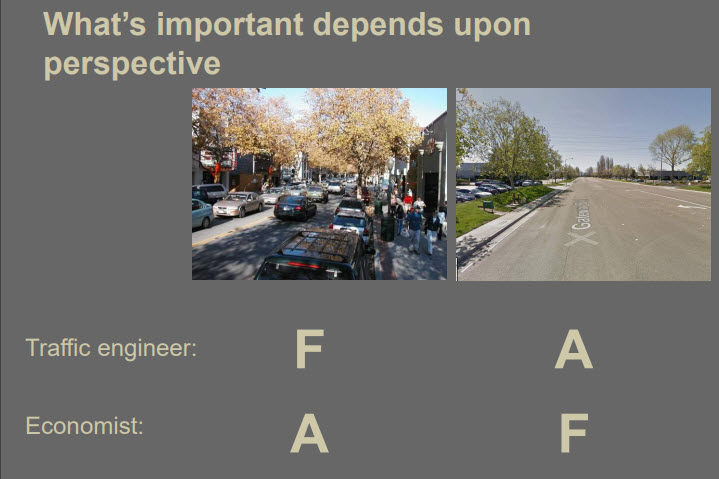

If it's only an "F" for a few minutes a day, you're wasting a lot of street capacity. Graphic by Jeffrey Tumlin

Traffic engineers use this data to justify road expansion projects. It’s a bit like showing up during that one holiday meal when you’re hosting every leaf on your family tree, and declaring that the dining room is cramped, so you should add a second story to your house.

Despite its limitations, LOS remains popular because it’s simple. When a street is clogged with traffic during peak use (i.e. supply equals demand), it earns an LOS grade of F. When there’s not another car between you and the horizon? Congratulations! You get an A!

Nicely put. Graphic by Jeffrey Tumlin

By overemphasizing LOS, we justify expensive, overbuilt streets that are dangerously inhospitable to people—just so folks who use the least efficient form of transportation (single-occupancy cars) won’t be inconvenienced during peak travel times. In doing so, we ignore the many variables that influence the transportation system as a whole: land use and zoning, pedestrian comfort, bike safety, viable transit, trip generation, etc.

But what about the Level of Service for people who walk and bike? Enter the Multi-Modal Level of Service (MMLOS), brought to you by the Highway Capacity Manual. (Because nobody understands the needs of pedestrians, cyclists, and transit users like the dudes who design the highways.)

Because it's easy to measure, the Pedestrian Level of Service (PLOS) focuses on four main variables: existence of a sidewalk, separation of pedestrians from motorized vehicles, motorized vehicle volumes, and motorized vehicle speeds.

If you want insight into the mind of a traffic engineer, consider “space per pedestrian,” a key metric based on the width of the sidewalk and pedestrian volumes. I love this because it’s so ridiculous.

I don't know...E looks pretty good to me! (Source: fhwa.dot.gov)

All that “space” is not a sign of success. Much of our public right-of-way is so hostile to cyclists and pedestrians that only the most desperate people—the folks with no other alternative—even attempt to walk or bike. If there’s a lot of space on a sidewalk, it’s usually because it’s a lousy or impractical place to walk; it's not comfortable or useful to people on foot. There are a lot of sidewalks like that in America.

So, does this sidewalk get an A? (Photo by Sarah Kobos)

In the interest of public safety, I propose the following alternative formula for calculating Pedestrian LOS:

When you see hundreds of cars, but only a handful of people walking or biking, that’s your clue that the street is an F. Conversely, when the streets and sidewalks are brimming with cyclists and pedestrians, you’re doing something right. It’s obviously comfortable and useful to people who would like to travel without an automotive exoskeleton. That deserves an A!

Studying the Winners and LOSers of Intersection Design

I’ve been thinking about all of this because I recently participated in a bike/ped count at a suburban intersection in my hometown of Tulsa, OK.

While traffic engineers focus on cars with a goal of preventing driver delays, I spent several hours focusing on everyone else. It was a fascinating experience that I recommend to anyone who cares about cities and the people who live in them. Every street and traffic engineer in America should be required to intimately observe their creations, because it shows just how hostile our streets are to their most vulnerable users.

If you care about fairness and equity—if you believe that the public right-of-way should serve all members of the public, not just those lucky and wealthy enough to drive a car—I encourage you to spend some time watching people as they attempt to interact with the infrastructure. It’s a humbling experience.

Pick a place to study and find an observation point.

A good place to start would be a local “hot spot,” which is the nice way to say “a dangerous street or intersection where people who walk or bike are routinely killed by people driving cars.”

I selected the intersection of South 51st and Yale in Tulsa, OK because of the number of folks I’ve seen playing Frogger across six lanes of traffic at every hour of the day and night. I wanted to learn more.

To observe the area, I looked for a place with an unobstructed view of the intersection as well as the streets and sidewalks leading up to it. I was also lucky to have some shade, which is critical when surrounded by asphalt in the summertime.

Capturing Data

I performed two 2-hour surveys: one on a weekday morning from 7-9 a.m., and another on a Saturday from 8-10 a.m. Because I was performing the count for the local Municipal Planning Authority, I used the tally sheet they provided.

Sample bike/ped count form

Column headers on the form identified 15-minute segments with separate rows for male and female cyclists and male and female pedestrians. We were also instructed to note the number of people using assistive devices. I modified my form to add space for mid-block crossings and the number of transit users getting on/off buses at nearby stops.

Just a Typical Suburban Intersection

Just a typical suburban intersection. Photo by Sarah Kobos

The intersection I studied is a good example of what happens when you prioritize the reduction of motor vehicle delay over every other concern. The intersection has two to three travel lanes plus two or three dedicated turn lanes for every direction of travel. Pedestrians hoping to walk north or south must cross 7 lanes of traffic, or about 100 feet in distance; pedestrians walking east or west must cross 8 lanes of traffic or about 115 feet.

Think about it. A person walking 3 miles per hour will require about 23 seconds to cross 100 feet. A car traveling 40 mph (the posted speed limit in the study area) will traverse 100 feet in less than 2 seconds. In the time it takes a reasonably able-bodied person to cross the street, a car going the speed limit will travel over a quarter mile.

Despite proximity to one of the city's largest parks, a hospital, a couple dense job centers (mostly health care and shopping), and quite a bit of multi-family housing, there are no bike lanes. If you want to play in the park, you’ve got to drive. The two stroads that make up the intersection function much like the Berlin Wall, preventing thousands of kids and adults who live nearby from accessing jobs, shopping, and recreational opportunities.

About that infrastructure....

There are sidewalks on both sides of the street in the study area, but they are located uncomfortably close to the high-speed travel lanes (sometimes abutting the curb, sometimes with a narrow grass buffer). In addition, the sidewalks are sliced and diced by dozens of 30 to 36-foot-wide driveways, negating what little protection they offer pedestrians.

Why do curb cuts matter? Driveways that intersect sidewalks effectively put pedestrians in a travel lane. In the video below, an elderly man crosses a 36-foot-wide commercial driveway. It takes him about 30 seconds. In that time, a car going 40 MPH will travel a third of a mile.

The Things You Notice When You Pay Attention to People

When we design for cars, we create really horrible places for humans. Here are a few things I wish the traffic engineers understood about the intersection they built:

Pedestrians prefer parking lots to shitty sidewalks. By cutting through parking lots, pedestrians in car-centric places are able to distance themselves from dangerous, high-speed traffic. Being farther from the street also gives pedestrians time to react to cars entering and exiting the multitude of commercial driveways. By walking at least 15 feet away from the street, people I observed were able to give themselves the necessary buffer zone to mitigate some of the most dangerous elements of the auto-centric design. This in no way suggests that these are comfortable, desirable, or dignified pedestrian routes. But it’s better than the alternative.

Cyclists are the main users of suburban sidewalks. Since riding on the street is a suicide mission, the sidewalks function as a semi-safe pathway for people on bikes. Largely ignored by pedestrians due to their proximity to high-speed traffic, the sidewalks provide a somewhat better experience for cyclists. At least they are physically separated from the cars (except for all the curb cuts), and offer a direct route along the road. Riding on the sidewalk is still terribly dangerous, due to the number of conflict points with turning cars, but it’s not an absolute death sentence. Every cyclist I counted chose to ride on the sidewalks instead of the streets in this location.

Mid-block crossings are scary, but at least the cars are only coming from two directions. Photo by Sarah Kobos

Pedestrians don’t cross at complex intersections: they cross mid-block. Given the overall complexity of crossing 7 or 8 lanes of traffic with multiple protected turn lanes, it’s no wonder that most people avoided the intersection. While Mad-Eye Moody might be able to watch for cars in all the necessary directions, most of us feel physically threatened when crossing enormous intersections.

Protected right-turn lanes are especially dangerous as they encourage drivers to turn right-on-red without stopping. And if you’ve ever watched drivers turning right on red, you know that most folks turn right while looking left, literally turning a blind eye to the people in their path.

Don't believe me? Watch the video below.

By choosing to avoid the intersection and cross mid-block, pedestrians are making a surprisingly rational decision.

- You only have to deal with traffic traveling in two, not twelve, directions.

- There are fewer lanes (thus, a shorter distance) to cross where the street is not bloated with turn lanes.

- When the street has a center median, it functions as an impromptu pedestrian refuge. It’s not great, but it’s better than nothing while waiting for traffic to clear.

- By crossing mid-block, you choose the timing of your crossing. As you walk down the street, you can be looking for a break in traffic that allows you to cross when it’s convenient. You avoid the extra delay spent waiting for the crosswalk signal at an intersection.

- Pedestrians always prefer the shortest distance between two points. Why waste steps walking to an intersection that feels unsafe anyway? Also, when surface parking lots are located on street corners, there’s no incentive to walk all the way around. Mid-block crossings enable people to cut corners, and enjoy the efficiency of the Pythagorean Theorem. In a hostile walk environment, the faster you reach your destination, the better.

Cyclists do cross at the intersections. Because every cyclist I counted was riding on the sidewalk, they utilized the crosswalks. With the advantage of speed, the 100 to 115-foot spans were less intimidating. (None of the cyclists dismounted to cross in the “pedestrian” crosswalks.) But drivers turning right on red were just as dangerous to cyclists as they were to pedestrians.

Transit users need shelter from the elements. While one of the bus stops in my study area included a covered bench, the other one didn't. Transit riders were expected to bake in the sun and rot in the rain. To avoid either of these outcomes, bus riders took advantage of the only shelter available to them: an abandoned gas station, where they could sit under the canopy while waiting for their bus.

There’s nothing like hunkering down between defunct gas pumps to make you feel like a valued human being. And yet we wonder why it's so hard to attract more "choice" riders. Hmmm.

Unless you have the physical prowess of an athlete, this place is not for you. At least once per hour, I would gasp out loud, as I watched a person on foot or bike nearly be hit by a person driving a car. On these sorts of stroads, both the speeds and the stakes are high. There’s no forgiveness. There’s no place for human error when traveling without the protective carapace of a car. Motor vehicle LOS, focused only on driver delays, is unconcerned with the frailty of human flesh and bone.

Many of the people I saw walking were elderly or had some level of physical limitation. You start to realize that folks who can’t afford cars also can’t afford knee replacement surgeries. Watching them attempt to function in this dangerous and hostile environment was heart-wrenching. There’s a terrible gulf between the speed and mobility of a person struggling to walk, and that of the murderous machines zooming past them on them on every side.

A Dignified Space

In a dangerously car-centric place, the people you see on foot are those with no other choice. They’re out in the heat and the rain, risking their lives every time they have to cross the street to buy groceries or walk to work.

Instead of helping connect people to the places they need to go, our city has built expensive public facilities that are both life-threatening and insulting to folks who don’t drive. We have effectively removed much of the public from the public right-of-way. And that's not fair.

I hope we can change. I hope we can begin to understand the inequity that’s baked into the current system. I’m hopeful that cities will realize that widening streets won’t solve our traffic problems, but it will continue to make things worse for people who don’t drive. That single-use zoning only increases vehicle miles traveled. That car-centric urban design discourages people who might prefer to walk, while wasting valuable land that could be put to better use than parking cars. That high-speed roads devalue adjacent land, making it impossible to maximize municipal revenues.

I’m hopeful that someday we’ll care about a different level of service: one focused on people and their need to feel safe, comfortable, and valued in the public realm.

Sarah Kobos has been a regular contributor for Strong Towns since 2016. She is an urban design nerd and community activist from Tulsa, OK. Her superpower is the ability to transform almost any topic into a conversation about zoning. Whenever possible, she explores other cities and writes about urban design and land use issues at AccidentalUrbanist.com.