3 Strong Towns Lessons From Around the World

At Strong Towns, most of our work and our commentary have always been focused on North America, and predominantly the United States. There is a simple reason for this: all our staff and most of our writers are Americans, and that’s where our expertise lies. It’s where we’re most deeply acquainted with the political and financial institutions that shape cities, as well as the history that provides context to the problems we face today.

However, there is nothing uniquely North American about the issues we write about, many of which are fundamental to creating strong, productive, resilient cities anywhere in the world. And there’s a lot to learn from cities and towns around the world: their successes, challenges, and how their urban form is and is not like what we’re used to here in North America.

Fortunately, our writers are a well-traveled bunch, and over the past few years, they’ve brought back some wisdom from abroad to share on our site. Here are some perspectives you might have missed the first time around on what Strong Towns advocates can learn from abroad, organized into three powerful lessons:

Lesson 1: You Can Do a Lot With a Little

Our illusion of wealth tends to make us blind to low-tech and/or low-cost solutions to the problems we face. If North America is the land of expensive, blinged-out, top-down solutions to urban problems, then much of the rest of the world is the land of the bottom-up, low-budget, improvised approach. And it can produce amazing results.

From Fes, Morocco, Gideon Weissman of Frontier Group reports on how children can play safely… because there are no cars to worry about in the city’s wild, colorful, labyrinthine 1,000-year-old medina. Why not take an urban design lesson or ten from this ancient role model?

Yet there are still plenty of ways we can bring more life back to our streets. We can narrow streets, widen sidewalks, and make public life more fun with outdoor seating for cafes. And we can experiment with bolder steps: Last summer, for three days, Boston closed Newbury Street to cars, resulting in thousands of happy people, and even games of ping pong.

We obviously can’t turn our cities into medieval medinas. But what if our streets had fewer cars and more cafes? What if kids could safely play in the street? What if there wasn’t so much damn honking? Imagine how our lives might be better. And we wouldn’t have to travel halfway around the world to experience it.

Our recently departed colleague (we wish her well in graduate school!) Rachel Quednau wrote a few years ago about the walkability of Cuba.

These photos provide some excellent illustrations of how a country makes do when it can no longer pay for its infrastructure—something we are now facing in our own country. I also wanted to share these because the photos that we often point to as examples of gorgeous, walkable places too often come from expensive, First World cities like New York, London or Tokyo. But Cuba is beautiful too, and proves that walkability is achievable no matter how much money your city has.

Regular contributor Andrew Price used a trip to Mexico as an occasion to contemplate the relationship between the country’s wealthy city centers and its peripheral slums, which, although humble, serve as a platform for incrementally building wealth over generations.

I have had multiple people tell me that out on the edges of town or in the poor rural villages of Mexico, people that could not afford to live in the cities would come out here, find a vacant parcel of land, and build a house.

When you drive through these communities, you will notice that many of them have the odd nice house. Instead of bare cement, it will be stucco with glass windows and a tile court yard. It seems as if when these villages grow, so do the economic opportunities that come when labor and wealth gets concentrated together.

With this collective wealth and the gains that come from concentrating it comes the ability to afford things that they previously couldn't, like paved streets. Where the wealth is more concentrated, the nicer the amenities become, because the community can afford better streets, shops, schools, parks, police protection, etc.

You Can’t Have it All, but You Can Have Most of What Matters

In the United States, it’s common to see “semi-rural” residences with the full complement of urban services such as water and sewer lines. Guest contributor Karen Treanor is living the DIY life in Tasmania, Australia, and gives the lie to common assumptions about how much publicly-provided infrastructure is really necessary to live well in the countryside.

Strong towns require strong citizens: people who learn to take control of their lives and do for themselves things that are doable. Our great-grandparents were tough survivors who did a great deal for themselves before there were so many services done for them. Should we be emulating them before we forget how? It’s something to think about.

Lesson 2: Public Policy and Creative Activism Really Can Make Cities Safer

A lot of people are killed by cars in the United States every year. And there’s a certain brand of fatalism about it that feels uniquely American. “Accidents happen.” “This is why you need to be more careful when you cross the street.” “Nothing can be done about it.” In some other parts of this world, this assumption seems far less pervasive—and they’re showing us that, in fact, things can be done if we have the will to do them.

Alex Pemberton wrote a three-part series for Strong Towns on the aftermath of a fatal traffic collision in Wichita, Kansas. This article, the second part, describes the origins of Vision Zero, the campaign to end all urban pedestrian deaths, in Sweden in 1967:

At the heart of Vision Zero and its effectiveness is the notion that the design of roadways has the most significant impact upon the safety of users. Rather than the approach of past decades, in which cities and nations focused on improvements in safety technologies and increased enforcement — both approaches which carry significant ongoing costs to both the public and private sectors — Vision Zero introduces the idea that if safety is enforced by the very design of roadways, enforcement and technology can be used to enhance an already-safe system.

When Vision Zero first launched in Sweden, the country recorded seven traffic fatalities for every 100,000 residents; by 2014, that number had fallen to less than three, despite a significant increase in traffic. For reference, traffic fatalities occur at a rate of 11.6 per hundred-thousand in the United States.

Sweden now has the world's safest roads, with Vision Zero having made such a tremendous impact that it has since gone global.

The Human Side of Traffic Calming (Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Disorder)

If government policy is not your thing, maybe whimsical grassroots activism is. Tactical urbanism wizard Marielle Brown shares with us how zebras, mimes, and masked superheroes are getting traffic to slow down and drawing attention to pedestrian safety in Latin America and elsewhere.

In Bolivia, the zebras show that people can and do start driving slowly when they are confronted by uncertainty, intrigue, and some gentle derision. When streets are more interesting and complex, people driving (generally) slow down in order to better understand what is going on, and to be able to react to whatever happens next. This is not a peculiar Bolivian trait, but rather universal human behavior that can be observed around the world.

Lesson 3: The Patterns That Define A Resilient Place Are Universal

Strong Towns founder Chuck Marohn reflects on his first trip out of the country, which was to Italy in 2000. Getting to know Italian and other European cities—places that have endured centuries of change because of their deeply resilient characteristics—helped revolutionize Chuck’s understanding of what’s wrong with the way we build and finance contemporary cities here in America.

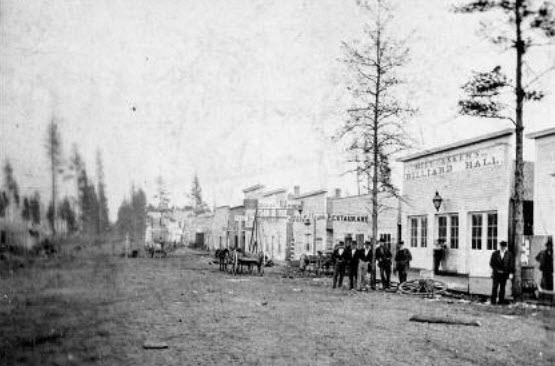

Why don't we have a Milan here in the United States? Easier still, why don't we have a Stresa (Italy, population 5,000) or an Avignon (France, population 95,000), two cities of immense beauty, character and, I am quite certain, financially able to maintain their basic infrastructure? Years ago, I would have believed it was because our cities were younger and had not had the time these great towns of Europe had. Then I came across this picture of my hometown of Brainerd and realized what had happened.

Everything you see in that picture from 1894 is now gone. In its place are a bunch of parking lots, abandoned buildings and very low rent, marginal establishments. As James Howard Kunstler wrote me once in an email, my hometown -- like so many other American cities -- simply committed suicide.

We’re Not Dumber Than Our Ancestors, We Just Have Power Tools

Regular contributor Spencer Gardner suggests that ancient civilizations were not immune to the hubris that can lead people to overreach, make stupid decisions in the name of grand visions, and ultimately drive their economy into the ground. However, our modern technology and the energy at our disposal makes us capable of doing far more damage when we succumb to that most basic of human foibles.

Over millennia of trial and error, our ancestors developed cultural conventions that tended to curb the greatest excesses and dull the force of the natural cycles that we’ve faced since we first crawled out from the ocean millions of years ago. We now face a double-whammy: the cultural forces once responsible for instilling virtue and a sense of shared destiny in each person — as imperfect as those cultures were — have been undermined at the same time that we’ve amplified the potential energy wound up in the system, ready to fling us groundward from the heights we’ve reached.

Johnny Sanphillippo observes the commonalities found in cities across the world, developed by people with vastly different cultures. The traditional development pattern—walkable, incremental, fine-grained, mixed-use—is a feature of all civilizations because it works, and it’s resilient.

On the other side of the planet we see the same traditional development pattern in Japan. Notice the small ground floor shops with modest living quarters above. Cosmetic differences aside, these machiya (shop houses) perform in exactly the same manner as the row houses and neighborhood corner shops in Philly. This architectural convergent evolution is a direct reflection of the resources, technology, and level of social organization which happened to be very similar in both places.

(All photos by the linked articles' respective authors unless otherwise credited in those articles. Top photo by Johnny Sanphillippo.)

Sometimes even the most well-meaning features of our cities present challenges to different people. What struggles would you observe in your community if you pictured it from someone else’s perspective?