The Catch-22 of Retrofitting the Suburbs

I believe in the incremental development of cities. Make a small bet on a small investment—a business, a building, a park, a bike lane, a farmers' market—and see how it works out. Adjust, try again. Lather, rinse, repeat. When hundreds of innovators are constantly doing this, and learning from each other, a great place results. That's how basically all of the great cities of human history have grown: in an emergent, not a neatly orchestrated, way.

But the most convincing intellectual challenge I know of to this incrementalist approach is a simple, almost mathematical observation: sometimes, you have to go uphill before you get to go downhill. Sometimes you might have to fight the current. You might even have to make a place a little bit worse before you can start making it a lot better. Sometimes you might have to destroy the village in order to save it. And there are some tough outstanding questions about whether incrementalism, as a process and philosophy, is up to that task.

The other day, I wrote about the idea of "activation energy" with regard to transforming the character of a place. It's a borrowed metaphor. In chemistry, the activation energy of a reaction refers to the initial energy that needs to be infused into a system—via something like heat or pressure or a catalyst—to jump-start a chemical reaction that won't otherwise occur. Paper, left to its own devices, won't spontaneously burn up. But apply a match to it, and it starts burning. Once it's started, it will finish burning without further intervention. The match provided that activation energy.

A graph illustrating activation energy in this context: the first moves away from auto-oriented design are an uphill battle, before you reach a point at which a walkable development pattern starts to become self-reinforcing.

Something akin to activation energy applies to large-scale changes in complex systems like cities. There is a self-reinforcing aspect to urban design, particularly with regard to the dominant mode of transportation. In places where car-dependence is the norm, developers will build to accommodate the cars that they know are going to be present. That means lots of space devoted to parking, store entrances that face the parking lot, driveway curb cuts interrupting the sidewalk, and other design elements that make a place more comfortable for driving, but less conducive to walking.

An inverse, virtuous cycle exists in areas where there's little expectation that driving will be easy, comfortable, or cheap. Developers don't go out of their way to accommodate drivers in their plans, and as a result, the status quo persists: driving is the exception rather than the rule. Think of New Orleans's French Quarter, or New York's Greenwich Village.

These decisions are market-driven. They're driven by who the expected users of a building are. They are sometimes influenced by local regulations like parking minimums, but far from always. In suburban areas, it's common for residential and commercial projects to voluntarily include more parking than the (likely already substantial) minimum required by the code.

This poses a Catch-22 for those like me who think car-dependence is killing our cities—and I'm talking about killing both city residents (literally) and municipal budgets. Stated simply, the Catch-22 is this:

There is little incentive to design for walkability in a place that isn't already walkable.

It gets worse. Designing for walkability with an eye to the future in such places is likely to make things actively uncomfortable for drivers (read: most people) in the short-term. So when you ask developers to do it, you may be asking them to alienate their core customer.

This is the "activation energy" we need. But getting developers to provide it, and do their part to transform a car-dependent place into a place that doesn't require a car, can be an impossibly heavy lift.

So why even try? Why not let the city be the city and the suburbs be the suburbs? Here's why, in at least one specific (but, I think, highly representative) case.

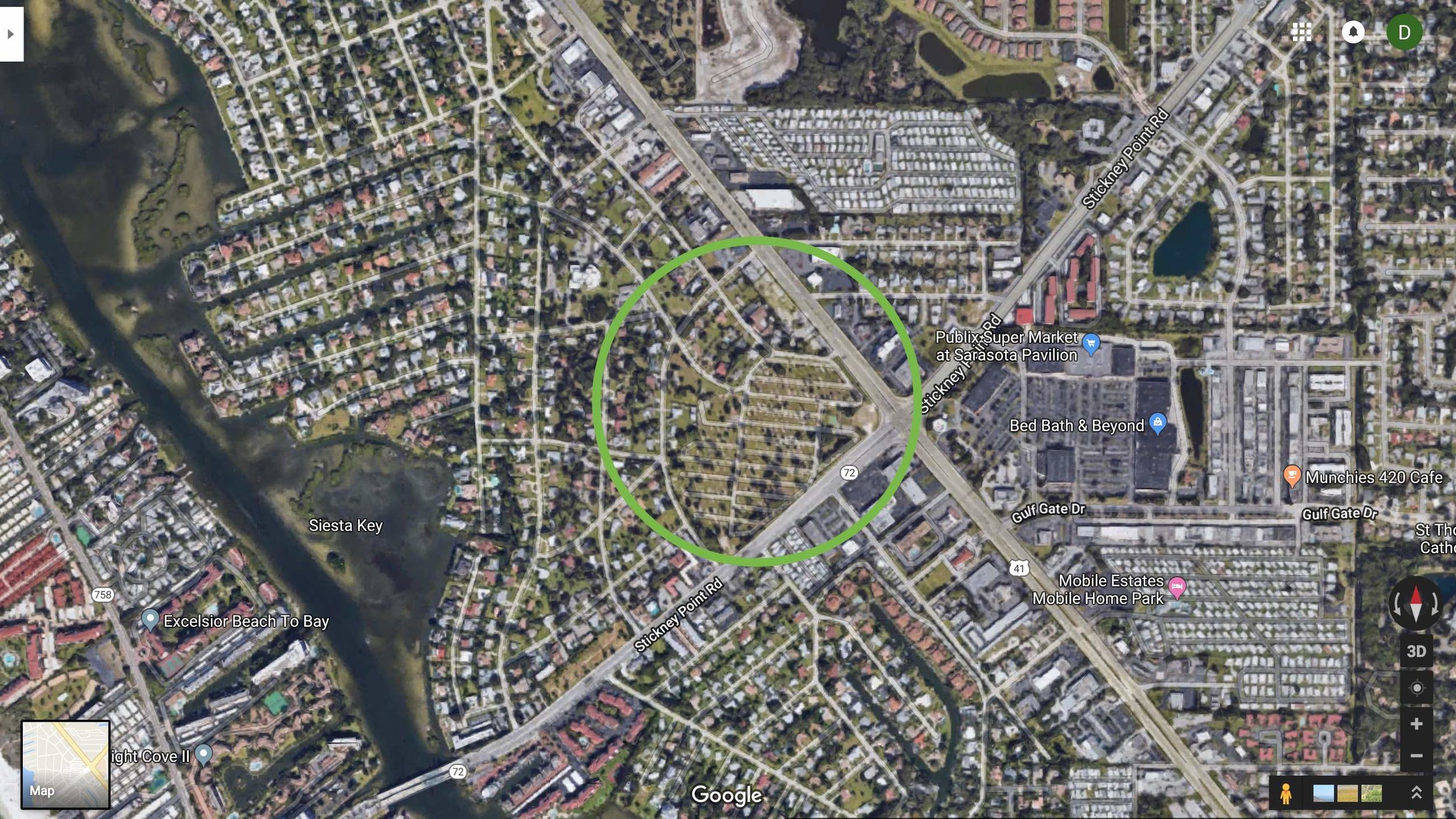

A typical section of suburban Sarasota County—note the pod-like subdivisions opening on to large arterial roads, and retail concentrated in large shopping centers. (Source: Google Maps)

The Case of Sarasota

I live in a place—Sarasota County, Florida—where only tiny pockets are functionally walkable. If you live and work in the downtown core or immediately adjacent neighborhoods (an area I estimate (generously) at 4 square miles), you might get away with not being tethered to a car on a daily basis, though you'll probably still own one. But if you live outside of that 4 mile area? Then you'll almost certainly need a private vehicle to get around.

For all intents and purposes, over 90% of the developed area of my county is a place where you have to own a car and use it daily to enjoy a high quality of life. To some, this may seem fine. But we have a national shortage of cities: there is strong evidence that the number of people who would like to live in a walkable, amenity-rich neighborhood far exceeds the number of people who are able to. The scarcity of walkable neighborhoods drives up the price of real-estate in them, and drives people out.

There's also the pressing question of our fiscal future. As I mentioned in my previous piece, the geoanalysts Urban3 came to Sarasota a few years ago and did an analysis of the public return-on-investment of various types of development. They found that a typical suburban development in Sarasota fares poorly: it would take 42 years of public taxes just to pay off its own infrastructure, which likely wouldn't last that long. That's a money-losing proposition. (Downtown mixed-use, on the other hand, paid off its infrastructure in only 3 years.)

And a good 90% or more of developed Sarasota County qualifies as "typical suburban development." Have you ever heard of a corporation that's losing money on 90% of its products or services, and making up the difference on the last 10%? That's not a sustainable strategy, for business or for the public sector.

So, there's good reason to expand the reach of walkable, mixed-use development in this region into places that don't currently fit that bill. The question is how, and where.

Strong Towns has argued against suburban retrofit before, but it's hard, living here, not to feel that some amount of suburban retrofit is our only option. The walkable part of the region is just too small a share of the whole to say, "Let the suburbs be the suburbs."

If a hyper-suburban city wants to try to seed walkability and urban-style development, where should they do it? I think a reasonable answer, and one that many planners would offer, is the following: "At locations close to job concentrations and daily shopping amenities, and on major transportation corridors that could feasibly be served by greatly enhanced public transit in the future, reducing the need for residents to drive."

Keep those criteria in mind.

And now, let's look at two large development projects that are currently working their way through the public engagement and approvals process in Sarasota. I think they illustrate why suburban retrofit is such a tough proposition to stake our future on.

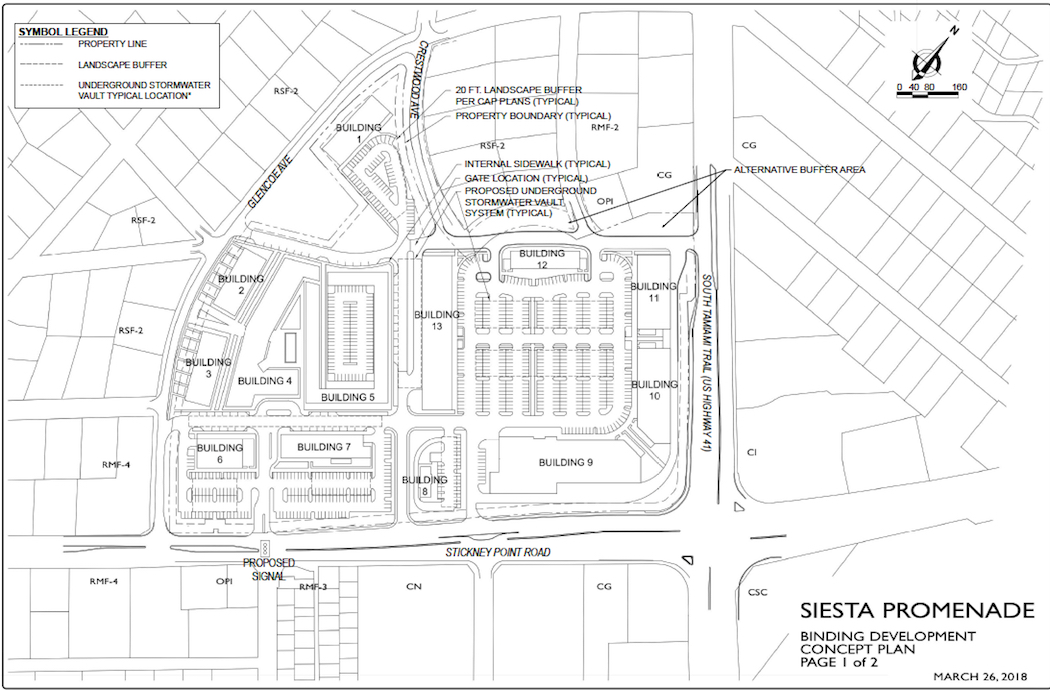

Project 1: Siesta Promenade

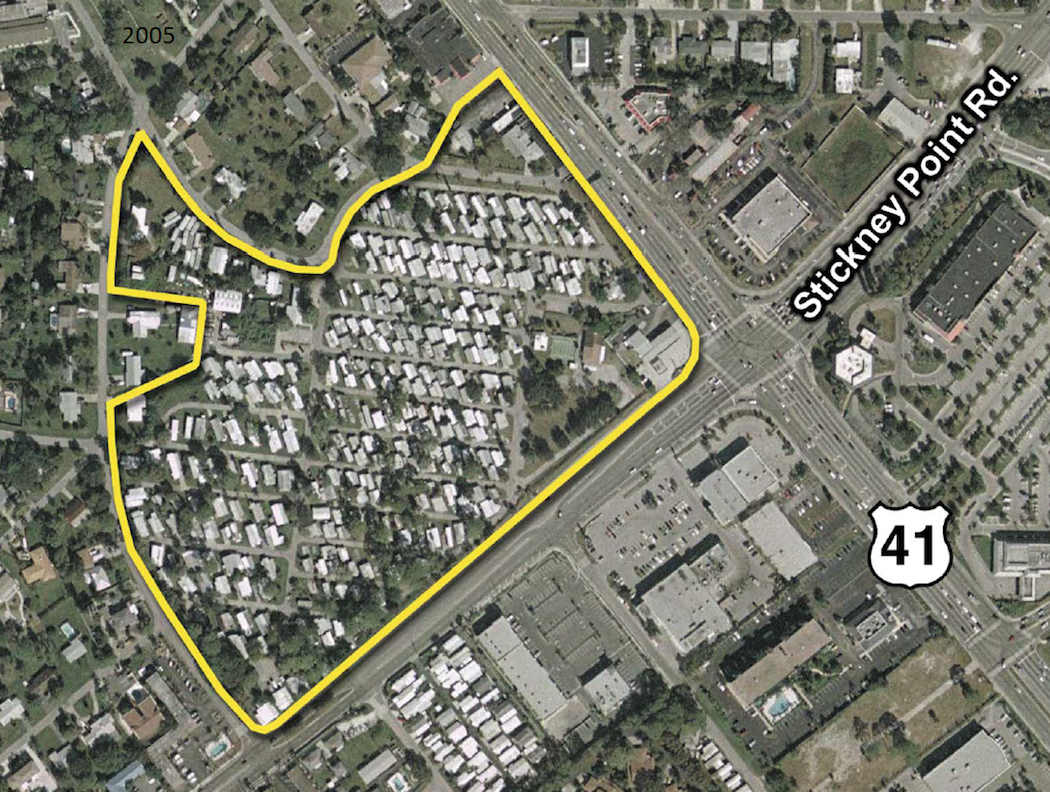

Siesta Promenade is a mixed-use project proposed for the 24-acre former site of a mobile home park at a busy intersection. It is currently proposed to contain 501 residential units, a 150-room hotel, and 140,000 square feet of retail space. The developer, Benderson Development, has applied for a Critical Area Plan—a way to consolidate rezoning and special exception procedures for a major, master-planned development, and evaluate it holistically—to increase the allowable residential density on the site from 13 dwelling units per acre to just over 20.

Siesta Promenade is designed to accommodate drivers first and foremost, as is apparent from the ample amount of land devoted to parking in the rendering and site plan above. The proposal is, without a doubt, an auto-oriented, high-density development, not a traditional urban form—see the Catch-22 above.

This has many in the nearby residential neighborhood, Pine Shores, up in arms. Their primary concern is additional traffic (the developer estimates a 6% increase at peak times) at an already-problematic intersection. The south side of the proposed Siesta Promenade site is defined by Stickney Point Road, one of only two roads that provide access to Siesta Key, a barrier island on the Gulf of Mexico that has twice been named America's best beach. For a good chunk of the year, Stickney Point suffers from near-daily traffic congestion as beachgoers back up, sometimes for half a mile or more, to get on and off the island.

And the intersection of Stickney Point and Tamiami Trail (U.S. Highway 41) is notoriously dangerous. This situation caused the Florida Department of Transportation to take the rare step of siding with neighbors in questioning a development proposal—unlikely allies, indeed. FDOT submitted a letter to Sarasota County noting the "astonishing" 175% increase in crashes at the intersection in just four years, frequent afternoon congestion, and the likelihood that intensive development nearby could require major changes to signal timing and turn lanes.

A lot of traffic concerns are overblown, but I'm not so sure these are. I can imagine Siesta Promenade, as currently planned, making mobility and safety noticeably worse for those who live nearby. Pine Shores Neighborhood Alliance President Sura Kochman agrees.

“They are saying, ‘Don’t exacerbate the problem that already exists. Be careful about what you approve on this site,’” Kochman told the Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

And yet, Siesta Promenade is located on a prime infill site, along two major transportation corridors that are as good candidates as any for future high-frequency bus services (BRT has been floated). It's within easy walking distance of a grocery store and to Gulf Gate, a phenomenally successful business district comprised of an eclectic mix of bars, restaurants, and mom-and-pop shops. And it's very near Siesta Beach, the preeminent regional destination and a major employment center.

If you want to site high-density multifamily housing in the suburbs at a location where it will contribute as little traffic as possible to the overall street network, and have the greatest chance of seeding a new walkable, urban node over the long run, you couldn't pick a better spot. Siesta Promenade checks every box.

If mixed-use, compact, relatively dense development in the suburbs is not appropriate here, then where is it appropriate?

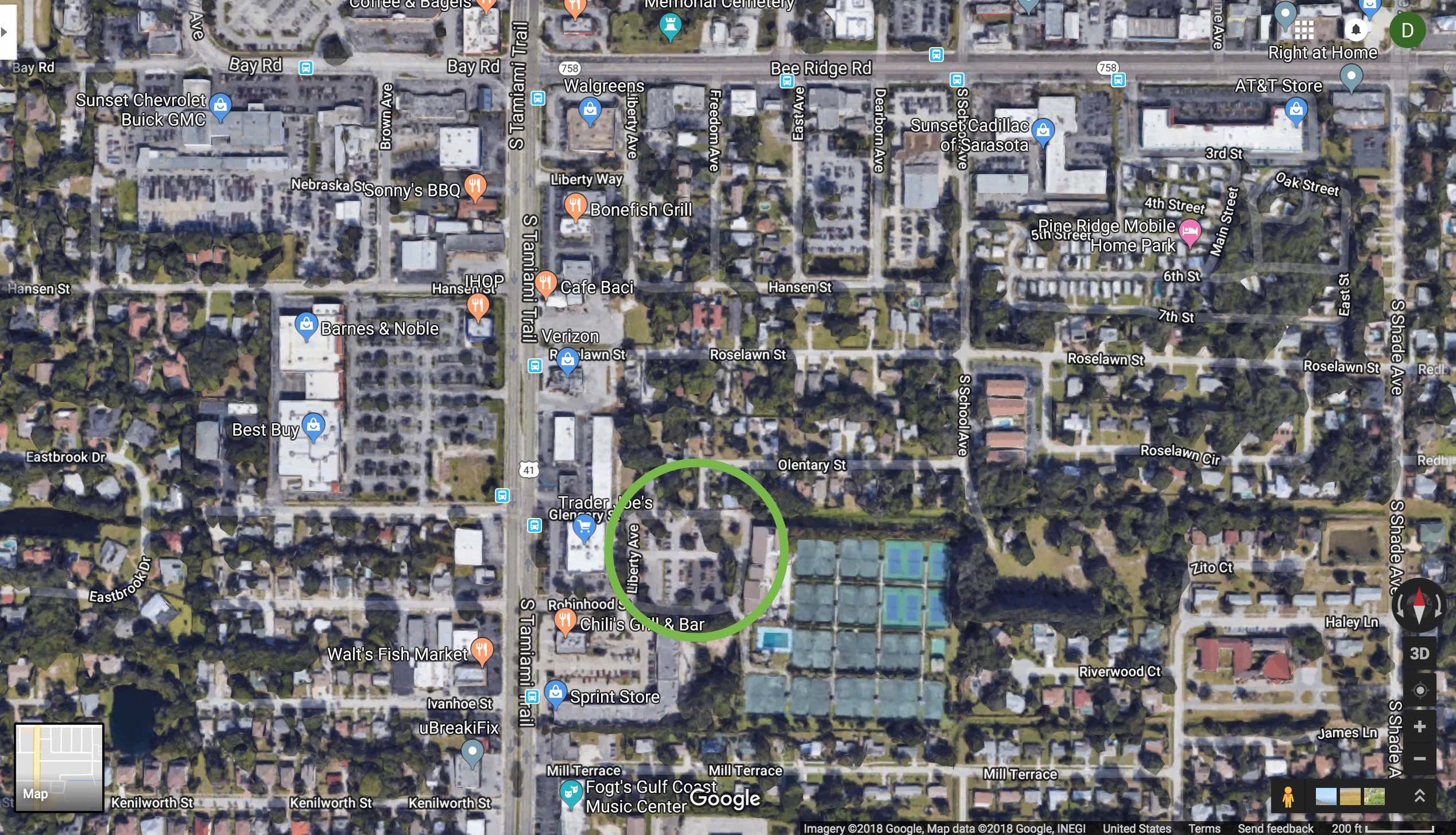

Project 2: Bath and Racquet Club

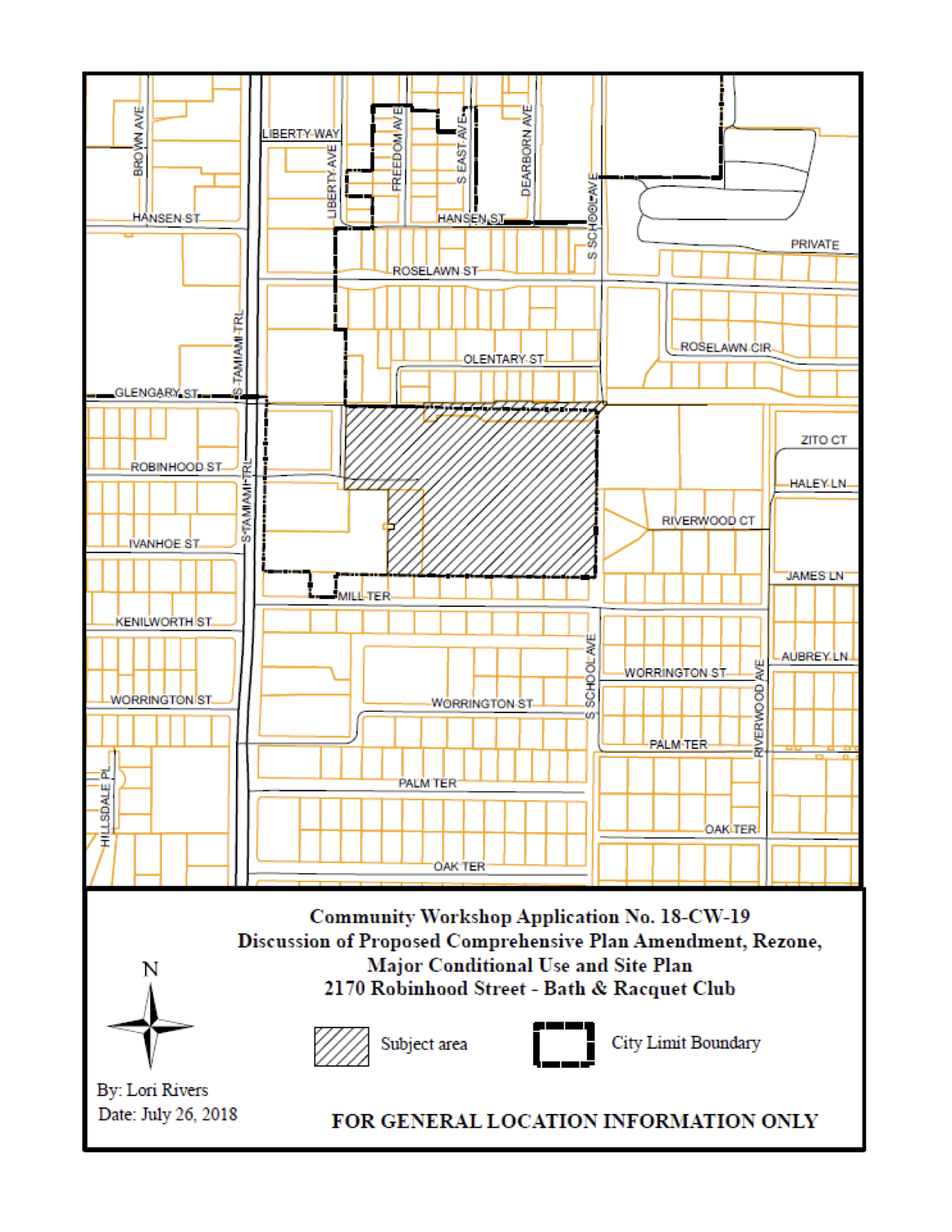

A couple miles north of the Siesta Promenade site, the Sarasota Bath and Racquet Club has proposed developing housing on an underutilized parking lot it owns. According to the Herald-Tribune, current plans would include 150 to 180 residential units and up to an additional 27 affordable housing units. There will be several three- and four-story buildings and one in the center which is seven stories.

The Bath and Racquet Club proposal has also spurred fierce opposition from neighbors over height, density, and traffic, as the Sarasota Observer reports. This development site is in a congested area behind a very popular Trader Joe's store. The store's parking lot routinely causes traffic snarl-ups on the side streets that serve it, and these are the same streets that would serve B&RC's residents. There is a very good chance that residents would enter and leave the development via a back route, down quiet neighborhood streets, rather than deal with the Trader Joe's chaos. This could be legitimately disruptive.

On the other hand, we have to remember that this development site is directly behind a very popular Trader Joe's, which means its residents would rarely have to get in their cars to go buy groceries. Like Siesta Promenade, the Bath and Racquet Club site is near the intersection of two large arterial roads that would be perfect for future bus rapid transit, providing a quick, painless connection to downtown and large employers such as Sarasota Memorial Hospital. Within walking distance is the Westfield Southgate Mall, which has been recently redeveloped as a dining and entertainment hub. Finally, not far from the site is the other one of the two bridge accesses to Siesta Key, South Sarasota's single biggest draw.

I repeat: if mixed-use, compact, relatively dense development in the suburbs is not appropriate here, then where is it appropriate?

The Chicken or the Egg?

Whatever my sympathies for these projects in principle—we've got to start allowing this stuff somewhere, right?—I don't think the opponents of these projects are being unreasonable. They're basically making the common-sense argument that if you cram hundreds of new people and their cars into an already-congested area, localized congestion is likely to get worse.

It'd be nice to imagine that many of the residents of these buildings won't drive, but let's be realistic: these proposals are isolated enclaves of high density in low-density suburbia. People will drive.

The congestion problem, we have argued before, is attributable to suburban design: a hierarchical road network that funnels traffic onto large arterials. This is a recipe for congestion far worse than we'd experience if we had a well-connected street grid with many routes from A to B. But reconnecting that grid would be a very long time coming.

And a lot of the problem is suburban design not even in the immediate vicinity of these proposals. It's a whole system. Beachgoers from all over the county funnel through the major intersections adjacent to these two projects. And they're almost all driving, because their own neighborhoods afford no better options.

It's a serious chicken-egg problem.

I'm torn about these two projects, as I said. I think they represent the worst of both urban and suburban, but possibly also a bridge to something better than the status quo in their respective locations. I want walkable nodes to exist at U.S. 41 and Bee Ridge Road, and at U.S. 41 and Stickney Point, and that means significant new development around those intersections.

It just seems that getting there from here is going to involve some pain. You have to go uphill out of the valley before you can go downhill. You might even have to destroy the village in order to save it.

Or do you?

I think there is an alternative, but it's one that has thus far been completely off the table because of a whole host of regulatory, cultural, and financial barriers.

Trying to manufacture a node of walkable, traditional urban development out of whole cloth is an awkward endeavor, but taking the part of the city that already has that form, and letting its radius grow, makes sense to me. Let it grow incrementally up, incrementally out, and incrementally more intense.

There are neighborhoods within 2 to 3 miles of downtown that, by this logic, should be open to the next level of development. Let single-family homes become duplexes and triplexes. Let small apartment buildings, 8 to 12 units, go up on corner lots. Let mom-and-pop stores and cafes open in these areas to serve growing populations.

This slideshow (photos by me) illustrates small apartment buildings, duplexes, and triplexes coexist in a neighborhood adjacent to downtown Sarasota. What if we allowed this sort of "gentle density" in more places than we do now?

These are neighborhoods within cycling, ride-share, even (well, maybe not in August) walking distance of downtown. A lot of them still deal with significant problems of poverty and poorly-maintaned older housing stock, so a wave of small-scale investment could set off a virtuous cycle.

But these areas have been declared largely off-limits to change. Virtually the only new construction in the neighborhoods I'm describing has been teardowns of single-family homes to build bigger single-family homes. Downtown Sarasota is in the midst of a construction boom, but step outside the boundaries of what is legally zoned "downtown" or "downtown edge," and you're in instant suburbia.

What if a 2-mile walk starting in the downtown core instead saw you passing high rises, then 5-story buildings with ground-floor retail, then Missing Middle apartment buildings and cottage courts interspersed with the occasional corner store, then a mix of duplexes, triplexes, and single-family homes, in succession, before finally reaching the single-family residential neighborhoods that dominate the county now?

How many more people would a walkable lifestyle be accessible to, then? The catch is that neighborhoods adjacent to downtown would, in 20 years, look more like downtown does now. The next ring beyond them would look like the inner ring of neighborhoods do now: with a robust mix of single- and multi-family housing options. And so on.

This is how cities used to evolve. But everything about our current codes precludes it, and I hear a widespread, probably accurate, assumption that massive public pushback would result if we tried to pass some of these changes.

So instead, the recognized need for infill development takes the form of mega-complexes at sites which, in theory, could be appropriate for that some day, but where it's completely alien to the current land use and transportation pattern. And the neighbors see plans for clusters of 5-story buildings and, not unreasonably, freak out.

The likely end result of the Siesta Promenade and Bath and Racquet Club proposals, if I had to wager, is that they will be significantly scaled down and then approved. There will be ample parking, enough to likely prevent true walkability from developing—because getting anywhere will mean a long march across hot asphalt, as if the stroad intersection with the "astonishing" crash rate weren't deterrent enough. Access points will be designed to keep traffic off neighborhood streets and funnel it onto congested arterial roads, instead of restoring a functional grid. We'll get more housing density than currently exists near those locations, but we won't get the true seeds of vibrant nodes of transit-oriented development.

What we'll get will be watered down, because truly transformative development would make things too inconvenient for drivers. That's the activation energy you have to clear to do large-scale suburban retrofit. Good luck.

(Top photo source: Johnny Sanphillippo)

Our most famous case study revealed the high cost of auto-oriented development. But what if a little creative rearrangement could make things a whole lot better?