My Journey from Free Market Ideologue to Strong Towns Advocate, Part 5: Commercial Development

This is the fifth part of a multi-part series, My Journey from Free Market Ideologue to Strong Towns Advocate.

In my early professional career as an engineer and a planner, I looked around and saw a world that could be explained through the free market prism I had adopted. In retrospect, that prism was ridiculously simplistic (and wrong), but at the time it could be summarized as:

Outcomes I Like = Result of a Free Market

Outcomes I Don’t Like = Result of a Distorting Government Intervention

I also strongly believed that growth and economic activity were the measures of a free market. When growth was up, when economic activity was increasing, that indicated things were trending in a free market direction. When growth was elusive or economic activity was stalling, I instinctively looked for a distorting government intervention to blame.

And since my job as an engineer was to build the infrastructure needed for growth, and my job as a planner was to create an environment where economic activity flourished, I found no contradiction between my work and my belief structure. In fact, my work was a fulfillment of my beliefs.

That is, until I started questioning my foundational assumptions. I’ve already detailed the economic analysis we did on local infrastructure for a highway project, the Quantum Theory of Economic Development and the proton smasher I found by examining cul-de-sacs. My professional colleagues were starting to acknowledge that residential development might not be so lucrative, but only because I wasn’t factoring in all the growth and economic activity they created. My next stop was to dig into those numbers.

Creating Economic Activity

I’m going to start with a current example because it just crossed my desk and makes the same point. My good friend Joe Minicozzi is from Rome, New York. I had a chance to visit Rome with Joe and get the insider’s tour, including the Fort Stanwix National Monument, a reconstructed colonial-era fort plopped down in the middle of Rome’s downtown, multiple blocks of which were razed in Urban Renewal to facilitate the project.

You can read all about it on the National Park Service website, but also watch this short video to hear first-hand the thinking behind this move. In response to the decline of the 1930’s and the shift in investment patterns from suburbanization, the basic idea was to transition the economy of downtown Rome from retail, service, and industry to tourism as a way to grow the economy, create jobs, and keep the city’s kids from all moving away. (I’ll note that Joe now lives in Asheville.)

It’s sadly comical to hear city officials say things like, “This one can’t miss,” and, “It’s practically depression-proof,” and then, “It’s going to cost you practically nothing.” It’s the same kind of cringe-worthy to listen to the economic development official explain how to hard sell this to the community, an art we’ve polished up a little bit in modern times while maintaining the general approach. Watching this video, it feels a lot like projects I worked on as a planning consultant in Minnesota.

Last month, the Utica Observer-Dispatch reported: Fort Stanwix a $6.1M Economic Boon for Rome Area. That sounds good. That sounds really good. In fact, if I were still the same free market ideologue I was back in the day, the kind that looked at ratings agency reports and bond market yields as affirmations, I would say that this sounded a lot like success. Even if the fort was a big government project, now we’re seeing the free market respond and generate a whole bunch of economic activity. That’s good for Rome!

Here’s how the local paper reported it:

Of the $5 million spent in the Rome area in connection with the park, about 40 percent of that was for hotels, or $2 million. Visitors spent about $1 million at local restaurants, $343,000 in local stores and $704,000 on gas, the report showed.

If I’m the mayor of Rome, this sounds great. If I’m the CFO, I’m shaking my head. Let’s say that entire $5 million was subject to taxation through the sales tax. If that were the case, here is how much each government entity receives from all that economic activity:

State of NY (4%): $200,000

Oneida County (4.75%): $237,500

City of Rome (no sales tax): $0

Yes: like my hometown here in Minnesota, Rome has no local sales tax. Rome’s local government is funded largely by property taxes. There can be a quadrillion dollars of sales generated in Rome, and the number of jobs can increase ten times, and it won’t impact the city’s cash flow except to the extent that it raises property values.

Now it’s great for the state budget. And it’s great for the county budget. And as the federal government has a number of ways of taxing transactions, including income and profits, it’s good for the federal budget too. But for the Rome city government, tearing down multiple blocks of taxpaying properties—even if they were in terrible shape at the time—and replacing them with a tax-exempt property, under the guise of creating economic activity, is a really terrible transaction. Absolutely devastating.

As an engineer and planner, I worked almost exclusively for city governments. These city governments needed revenue in order to operate. In fact, they needed to run a profit; that is, they needed their revenues to be at or above their expenses, and that needed to continue indefinitely. Working for the city, how could I justify recommending all these projects if they were going to cost the city money and reduce the city’s direct revenue? And how could I use the abstract notion of “economic activity” to justify that recommendation?

How could I honestly say to the families, business owners, and taxpayers in my community that paying me to give this advice was in their best long-term interests? Why would they take on the liabilities, and ultimately have their taxes raised and their services cut, for projects that had no chance of a financial return?

Further, was growth and economic activity really a measurement of the free market? Realizations that I had worked on projects like this one in Rome had me starting to question my foundational beliefs.

The Business Park

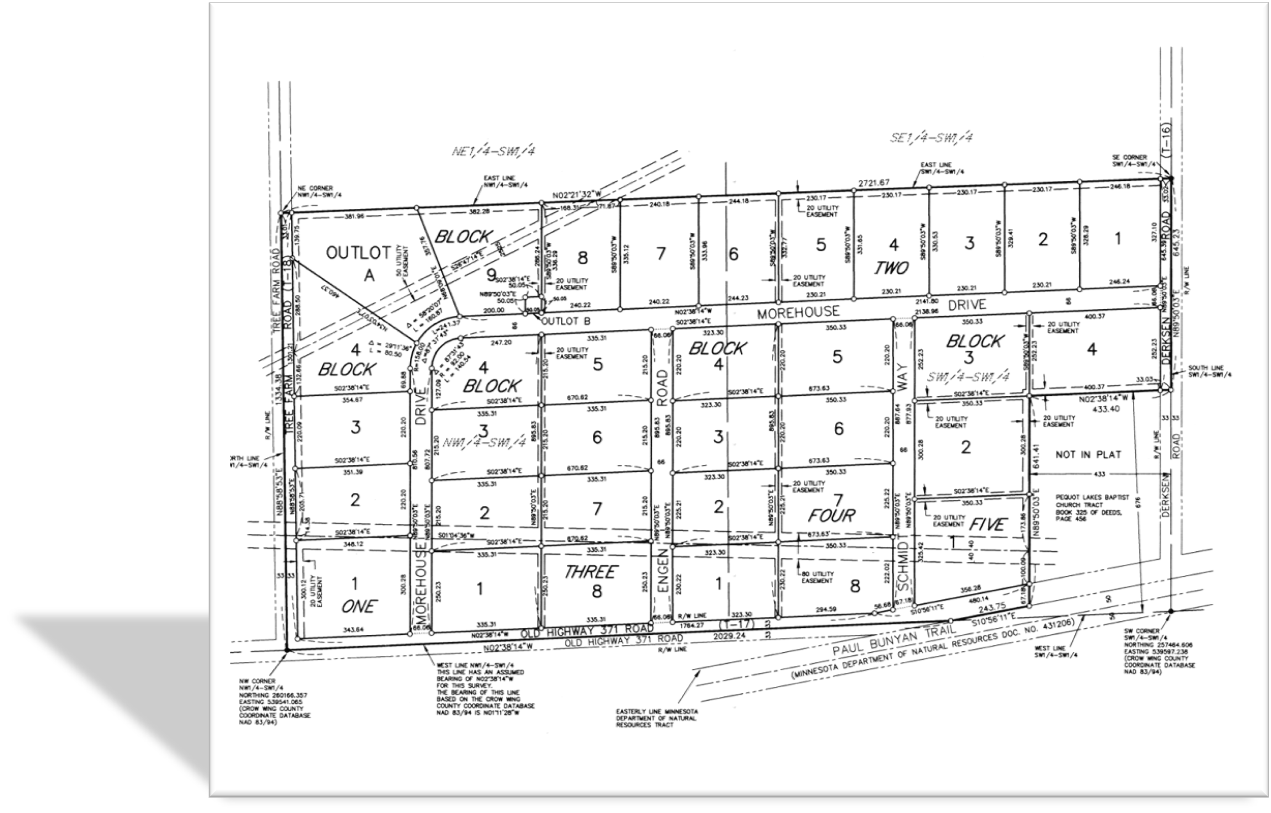

I had an opportunity to be part of a planning committee looking at doubling the size of the city’s business park. As a young engineer, I had been an inspector for the utility construction in the original park. Now, a decade later, that park was nearly filled, and city officials were looking to expand. My new role, as planner, was to clear any regulatory hurdles necessary to make this project successful.

The plans put forth by the city’s engineering firm would exactly mirror the existing park on land the city owned directly adjacent to it. This would be the same business park, constructed in the same way, on land that was essentially identical. In other words, in the Quantum Theory of Economic Development, this represented a perfect case study to do some proton smashing.

The engineer provided the cost estimate. That was pretty straightforward. I was then able to examine the existing park and the wealth that existed there. I assumed that the new park we were looking to build would turn out the same as the existing one, which everyone considered a success.

I went through city records and figured out the phasing in the existing park to see how quickly it was built out. I also tried to account for the tax subsidies that were given out and the fact that a number of the properties in the park were tax exempt. I put all of this into a spreadsheet and ran the numbers to see how long it would take the city to pay down the bond they were planning to take on.

They never would. If we repeated what we had done with the existing park, the revenues the city received didn’t even cover the interest payments.

I felt that couldn’t be right, so I went back and worked on my assumptions. I got rid of the tax subsidies. I got rid of the tax exemptions. It still didn’t work.

I assumed that the entire park would be build out within just five years. Then three years. Then one year. It still didn’t work.

Then I tried assuming, on top of these other overly-optimistic assumptions, that every single penny of new revenue brought in by this park would go to retiring the debt. If that happened, if the taxpayers of the city agreed to have their taxes raised to pay to plow the snow, fill the potholes, provide police and fire protection, and all the other routine services needed by this new expansion, then and only then—assuming all properties were developed within a year by fully taxpaying, non-subsidized businesses—could the city hope to retire the debt in 29 years. That’s a little longer than (but close to) how long the industrial street would be expected to last without needing major renovation.

Cities hard-sell business parks to their residents by citing the jobs and economic activity they will create. In a state like Minnesota or New York, where there isn’t a local sales tax, the real benefit of a business park is the potential for growing the tax base, adding wealth to the community that is reflected in the property tax receipts. In my experience, the business park was considered the premier way to grow a solid tax base—every community that could would build one—and I believed that to be the case. It’s not true.

I’ve since examined a number of these and found similar results. Here in my hometown of Brainerd, we have a business park that has had vacant lots for well over a decade (maybe two), yet we recently spent around $13 million running utilities to the airport for the chance at an air-oriented business park. Back-of-the-envelope calculations I did at the time (when it was still a $7 million project) suggested the city would need to bring in over $65 million in new tax base to make this pay off in a generation. There is no chance this will ever happen, and I will take all bets in any amount on that.

Circumstantial Evidence?

I’m not an academic. I don’t do research. I’m not going to write a white paper or publish in a professional journal. That’s for other people.

What I am is a rather bad engineer and a pretty poor planner. My greatest career limitation was that, instead of just doing my job, I spent too much time trying to figure out why we were doing what we were doing. And by this point in the story of my life—around 2008—I was pretty confused by it all. A little scared and a lot angry.

And with banks failing, housing prices collapsing, gas prices spiking, insane bailouts, and a crazy election cycle that didn’t touch on anything I thought important to it all, I found myself more and more on the outside looking in. I was the guy nobody wanted in their meeting, which is not a good career trajectory for a consultant, especially one with young kids at home.

I was screaming into the void, a voice in the wilderness, and nobody was listening. In retrospect, I can’t blame them; I was really angry about it all.

I had lost faith in my foundational beliefs, in the people I had relied on to guide my career, in the professions I had selected for my calling. Was there anyone else out there who was seeing what I was seeing? Was the whole world crazy or was I crazy? I wasn’t sure.

I sat down and started to write. I would soon find a whole bunch of people eager to help me figure this problem out. More on that in the next post.

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.