My Journey From Free Market Ideologue to Strong Towns Advocate, Part 6: Organic Markets in the Traditional City

This is the sixth part of a multi-part series, My Journey from Free Market Ideologue to Strong Towns Advocate.

There’s been a recurring strain of feedback to this series that is best represented by this comment on the last column:

I’m still not seeing where the indictment of the free market is, or where more intervention by the government or more government spending is going to be the solution.

It’s interesting to me because the idea of My Journey from Free Market Ideologue to Strong Towns Advocate has never been to describe an abandonment of market principles. This is not leading up to an embrace of government intervention or government spending as an antidote.

To the contrary, I’m trying to explain how I woke up to realize that what I thought was a market-based set of outcomes were not. How I came to understand government intervention at work in the entire structure of our markets and the outcomes they produce. How government spending—and the government assumption of liabilities—is the main factor in what I believed to be free market outcomes.

If you look outside the window of your home and believe you see the free market at work, you are mistaken. If you gaze across the dashboard at all that we have built and believe it is an expression of a free market, you are not seeing reality. And if you want to believe that it is—if you insist that somehow housing prices, interest rates, ratings agency reports, big box stores, strip malls and suburban subdivisions represent the free market at work—you are an ideologue.

I used to be an ideologue. I am no more.

Markets for Irrational, Fallible Humans

What I recognize today first and foremost is that markets are created by humans. Fallible humans. I cannot understate the influence that Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow has had on my understanding of human fallibility and irrationality. Humans (and I’m not exempting myself here) have an extraordinary capacity to rationalize nearly anything, to explain after-the-fact why we took a certain action or believe a certain thing. I have the Cognitive Bias Codex framed and mounted on my office wall as a frequent reminder.

If you’re open to experiencing something painful, watch this video of Jonathan Haidt giving a speech called The Rationalist Delusion in Moral Psychology. He shows the crowd interviews that push people to confront their own irrationality. It’s painful because, if we’re honest, we can see ourselves in them.

As I’m going through the exploration I’ve documented in this series, I came to the painful conclusion that what I thought was a market outcome was, in fact, the opposite. The post-World War II development pattern is, as I’ve said many times, the greatest government-led experiment ever attempted. (Read: The Conservative Case Against the Suburbs, which I wrote for The American Conservative back in 2014.)

And while there are market mechanisms deployed within it, the underlying structure tilts economic gravity in such a way that it distorts everything.

Want a single-family home? Sure, here’s a government-subsidized loan with a secondary market to absorb it. Want to live above your grocery store? Go ahead, but you’ll have to find your own financing.

Want a big box store with an international supply chain? Sure, here’s trillions in highway spending and standards inducing local governments to retrofit their entire community for semi-tractor trailers. Want a neighborhood hardware store? Go ahead, but everyone in your neighborhood is going to drive now because the highway through town is an uncrossable stroad and the federal government funds asphalt streets, not concrete sidewalks.

Want to start a Dunkin Donuts? Here’s an incredibly liquid capital market that can be accessed by those who qualify for seven-figure loans. Want to start a local doughnut shop in an abandoned storefront? Go ahead, but you’ll need to find a local benefactor because no local bank is going to take that risk unless you possess a ton of equity.

We can argue that all these options represent choices within the established marketplace, but I’m questioning the nature of the marketplace itself. The outcomes we experience and the choices we make are driven by the market we’ve established, with all of its distortions and subsidies. I used to believe that it was the other way around, that the market we see was something that developed to reflect the preferences of the public.

This marketplace is not serving our preferences. We’re serving the preferences of this marketplace. I could not longer claim that the widespread adoption and delivery of my preferences — at the time: a large lot, single-family home, with congestion-free transportation access to big box stores, strip malls, and fast food — represented something I chose freely, or something whose emergence I could trace back to a state of nature. If I wanted to remain an advocate of markets, I had to acknowledge that the outcomes I had come to prefer were not the result of a market-based system. Confronting this cognitive dissonance was painful and disorienting.

Ultimately, I started to ask myself: What does a truly market-based system developed and utilized by irrational and fallible humans look like?

My extensive reading of Nassim Taleb gave me a push toward an insight. Cities are complex, adaptive systems. They are organic, not mechanical. So at what point in the past did cities function more or less organically? The answer is debatable, but the work of Joe Minicozzi gave me a powerful framework to identify a turning point.

Financial Productivity

For those not familiar with Minicozzi and the group at Urban3, you’re missing out. I first met Joe when I shared a stage with him at CNU in Madison. His presentation blew me away, answering many questions I had about the revenue stream of cities. My presentation on expenses filled in missing links in his thought process. Our peanut butter and chocolate moment spawned an ongoing professional collaboration and a deep friendship.

I’ve written extensively about Joe’s work in my upcoming book, Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity. I could write much more here. The salient point for this conversation about markets is the sharp dividing line in financial productivity—value per acre—between pre-Depression and post-War development patterns. From my book:

The team at Urban3 has modeled hundreds of entire cities around North America. This massive data set has revealed a near-universal set of trends, results that are consistently observed in cities of all sizes, in all geographies, using all taxing systems, across the continent. These include:

Older neighborhoods financially outperform newer neighborhoods. This is especially true when the older neighborhoods are pre-1930 and newer neighborhoods are post-1950.

Blight is not an indicator of financial productivity. Some of the most financially productive neighborhoods are also the most blighted.

While there are exceptions for highly gentrified areas, poorer neighborhoods tend to financially outperform wealthier neighborhoods.

For cities with a traditional neighborhood core, the closer to the core, the higher the level of financial productivity.

The more stories a building has, the greater its financial productivity tends to be.

The more reliant on the automobile a development pattern is, the less financially productive it tends to be.

The traditional development pattern—even when blighted and occupied by the poorest people in our communities—is financially more productive than our post-war neighborhoods, regardless of their condition.

If we’re searching for what a market urbanism looks like—a true organic system, where as many distortions as possible are removed and we’re left with irrational, fallible humans transacting with each other as freely as possible—there is good reason to correlate that with the development pattern that persisted around the world for literally thousands of years prior to the 20th century.

As I confronted the fact that my engineering and planning advice — which itself was an extension of my market-oriented viewpoint — was making cities increasingly insolvent, creating growth but not wealth, I was forced to acknowledge that cities which developed before the currently accepted model of engineering and planning was put into practice were forced to respond to market feedback in ways that were painful, yet productive. Here’s what I wrote back in 2013 in my widely-distributed piece, The Fool Proof City:

For millennia, around the world, in different cultures, different continents and different climates, we built places scaled to people. It has only been the last 60+ years that we in North America gradually stopped walking and started driving. For thousands of years prior, we walked everywhere, and so our places were built around people who walked. While there were many variations on the theme, the spacing, scale and proportions of these places were very similar to one another.

They key insight here is that the knowledge for how to build this way -- those fundamental underpinnings of spacing, scale and proportion -- does not descend from a theory or a brilliant individual but from a collection of natural experiments that occurred over and over again for thousands of years. In other words, people suffered and even died trying different things, figuring out how to build places that would endure. The places that endured long enough to be copied were the ultimate strong towns. They were resilient politically, socially, culturally and financially.

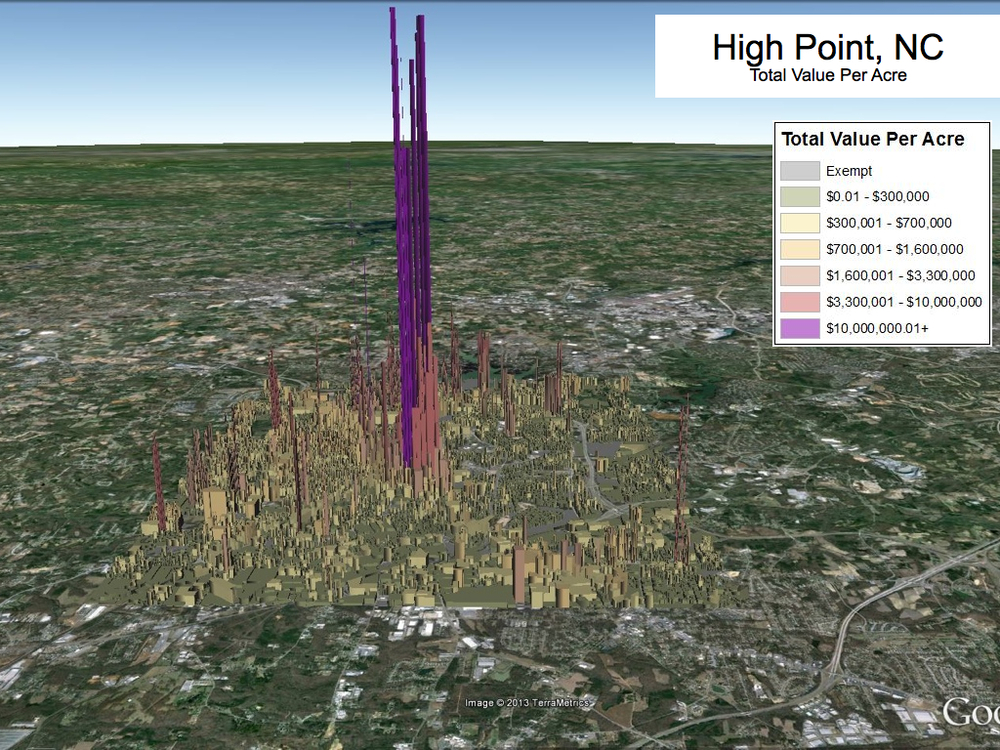

It is that last point I want to demonstrate today. The financial strength of the traditional development pattern is still visible today because the remnants of places built in that style still exist in many of our cities. Joe Minicozzi, one of today's most brilliant communicators, has taken data from all over the country and created amazing maps that show the financial productivity of different development patterns. He and I did some work in North Carolina earlier this year where he presented this map of High Point. The map shows financial productivity (total value per acre) of each parcel in the city with the height of the line representing the comparative productivity.

You'll never guess where the traditional downtown is at. (Hint: the purple in the middle.)

The thing that is most stunning about this is how dramatically more productive that traditional development pattern is. It is not just marginally more productive; it is many, many multiples more valuable than everything else on the map.

As I note in that piece, the traditional development pattern is so simple that it can’t be screwed up. It’s foolproof, the kind of stable situation an organic— dare I say “free”—market would establish when allowed to evolve on its own.

I’m almost ready to answer some questions that have been posed to me but first I need to expound on how a Strong Town would use markets and market feedback to build prosperity, and how those insights frame the way I look at local governments and the communities they serve.

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.