Making Normal Neighborhoods Legal Again

I've spent over two-thirds of my life so far living in anarchic environments where the rule of law did not prevail. It's a wonder I survived at all.

You see, when I was born, my parents lived in a duplex, in a neighborhood that isn't supposed to have any duplexes. You can look at the zoning map: "R4—One-Family Residential." And yet there we were, our home legally nonconforming in planner-speak that evokes the way a 1950s sociologist might have written about "social deviants": a young couple and a newborn saving up some money to buy a home while renting the upstairs unit from my aunt, who owned the house and lived downstairs (and provided no shortage of free child care!). It was the perfect stepping stone for us for a while. For much longer than that, it remained the perfect home and investment vehicle for my aunt, and home for her best friend, who replaced my parents as her tenant.

An unobtrusive duplex sits alongside single-family homes. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

We moved later to a single-family house with a nice big yard, next door to another duplex that would also be illegal to build today, but that is also grandfathered in because it was built before the prohibition took effect. I grew up next door to a succession of tenants, most of them nice people, that included families with kids my age; working-class roommates sharing the space to make ends meet; and young professional couples not quite ready to buy that starter home. Another duplex down the street was home to multiple generations of one family.

My neighborhood was safe, quiet, had highly-rated schools and a great regional park with a zoo. Some of those people who were my neighbors could never have afforded the ante of buying a home there, but they could rent—in homes that would be illegal to build today.

The official, sanctioned, on-paper "character" of this very normal neighborhood in a normal, Midwestern American city is single-family detached houses. That's the community’s agreed-upon vision for the area, according to the city. My aunt and her best friend and my working-class neighbors and that multigenerational family were excluded from that vision. As far as the zoning code was concerned, they were legally invisible. Present, but not expressly desired. Nonconforming.

For a good chunk of my twenties, I lived in a series of accessory dwelling units (ADUs)—backyard cottages located behind larger homes. These were in a neighborhood in a mid-sized Southern city zoned RSF-2, described by the zoning code as a "low-density single-family zone," in which "one and two story single-family detached houses will characterize allowed housing." ADUs are expressly not allowed in this neighborhood—but many exist, having been built before that rule took effect.

In this city, living in an ADU is virtually the only way for someone on a modest income—whether a young couple like my wife and me, a single working adult, or retirees looking to downsize—to live within walking distance of downtown. For us, that meant that we could live a car-lite—and carbon-lite—lifestyle, with one car and two bikes between us. For our various landlords, it meant a helpful income stream. For some of our neighbors, similar arrangements meant the ability to age in place.

All over the U.S., duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, ADUs, even small apartment buildings quietly exist in supposedly "single-family detached" neighborhoods. They're normal. They belong. They fill a vital need. But if you applied for a permit to build another one just like them today, you'd be denied.

All over America in cities big and small, the on-the-ground reality belies the legal fiction of “single-family neighborhoods.” There are 10,000 or so multi-unit homes hiding in plain sight in single-family districts in Seattle alone. You can find "illegal neighborhoods"—as in illegal to replicate today, despite that many are stable and prosperous and well-loved places—in Portland and Somerville and Lexington and Milwaukee and pretty much anywhere you could throw a dart at a map.

What's going on here?

Single-Family Zoning Was a Radical Experiment

We've been following the rapid shift of the Overton Window—that is, the range of policies considered mainstream and politically viable on a given issue—with regard to single-family zoning. When Minneapolis, in late 2018, passed a comprehensive plan that would categorically allow duplexes and triplexes in residential areas where they have long been banned, we praised the decision.

Now the entire state of Oregon has followed suit. Both houses of the Oregon legislature have passed House Bill 2001, under which Oregon cities over 10,000 residents can no longer ban duplexes—and cities over 25,000 must also allow triplexes or fourplexes—in residential areas. The governor is expected to sign the bill.

Seattle City Council member Mike O’Brien visits a backyard ADU in 2016. (Source: Seattle City Council via Flickr)

A day later, Seattle—never to be wholly outdone by its neighbors to the south—categorically allowed ADUs on single-family lots citywide. What's better, the Seattle legislation does this without any of the onerous restrictions—owner-occupancy requirements, unreasonable parking minimums, strange size and design restrictions—that make ADUs practically infeasible even in many places they're nominally allowed. You can even build two ADUs on the same property. Now, in Seattle, you can essentially have up to 3 modest homes on a normal residential lot.

These incremental but across-the-board (i.e. not targeted at a specific neighborhood or small area) upzonings have been portrayed, especially by opponents but sometimes by supporters, as a radical experiment or a novel strategy for solving pressing problems. They are neither radical or novel. They're better understood as a partial return to the historical norm: neighborhoods that are free to contain an eclectic range of housing types to match the eclectic range of households and needs that exist, and neighborhoods whose composition and physical form might evolve over time.

There's an important distinction to make here when we talk about ending single-family zoning. It's this:

Single-family housing has been around forever, and is not going anywhere. Single-family homes have existed ever since humans first built mud huts, and are globally the most popular physical arrangement in which to live. They'll almost certainly remain so.

Exclusive single-family zoning, on the other hand, is a historical anomaly, an invention of the 20th century. One might even call it a radical experiment.

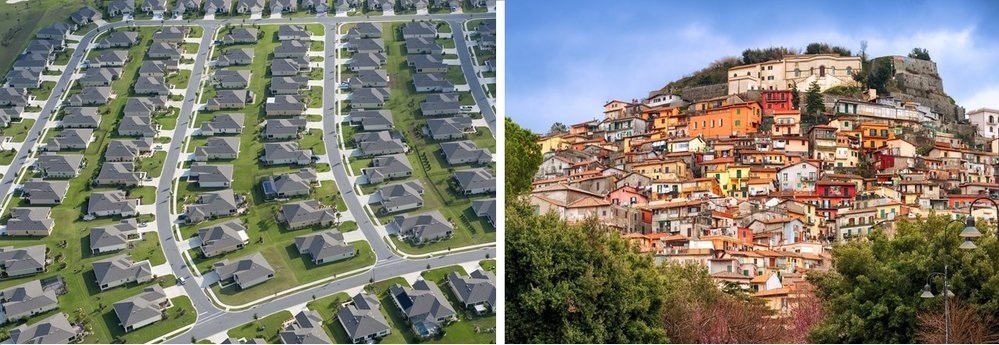

This historical anomaly is part and parcel of our grand post-World War II experiment in monocultural development—we now build whole neighborhoods conforming to a single template. We do it all at once, to a finished state, and then try to preserve the place under glass, never to change or evolve.

The legal vehicle for this approach is rigid, single-use zoning that segregates different land use patterns from each other. We’ve, in effect, replaced the diverse, complex ecosystem of a traditional neighborhood with the simple monoculture of a suburban subdivision: a place that is complicated (lots of rules and regulations) but lacks complexity.

And not only did we apply this paradigm to new postwar suburbs, but in city after city, especially in the 1950s through the 1970s, we downzoned neighborhoods that used to include the likes of duplexes, apartment buildings, and ADUs, and said "No more." This is how it came to be that my aunt could buy an old duplex in a neighborhood that bans new duplexes and live in it for 30 years.

Much has been written about why this shift occurred. In many places, racial politics was clearly part of it. Fear of neighborhood decline in an era that wasn't kind to inner cities motivated some downzonings. Apartments and renters became associated with decline, and so cities caved to homeowners demanding apartment bans in their neighborhood. In an insightful commentary on the subject, Slate’s Henry Grabar pointedly characterizes single-family zoning as an “apartment ban”—defined, in intent and effect, not by what it includes but by what it excludes.

But rigid, single-use zoning is also simply a part of the institutional mindset of the suburban experiment and the large-scale, corporate developers that have carried it out: efficiency and predictability require standardization, which requires monocultures. The heavy machinery used by a corn or soybean farmer to quickly till, water, and fertilize many acres is useless in a garden in which various species are interspersed. The mass-production model of the capital-D Developer is useless in an eclectic, mixed neighborhood.

The world mapped out by strict use-based zoning is all very orderly, and many individual homeowners have bought into the approach. You hear this focus on order in the way opponents of loosening zoning rules speak: “My home is my largest investment. The city owes me the certainty that the neighborhood around me won't change, in order to protect my investment.”

The problem? The real world is not so predictable or orderly. Economies change, employment patterns change, the population changes, and household composition changes (only 1 in 5 U.S. households is a nuclear family in a country built around single-family detached houses). A world built on fossil fuels is also finding that it, too, has to change. And so our neighborhoods must be allowed to change.

A Growing Sense of Crisis Motivates Diverse Advocates

There are more and more cracks in the facade of the suburban experiment. They look like crises that our landscape of homogenous single-family neighborhoods now stands in the way of addressing effectively. So whether your issue is climate change, or housing affordability, or racial justice and desegregation, or education reform, you're more likely than ever to have found common cause with the diverse coalition of groups pushing bills such as Oregon's HB 2001. The Sightline Institute's Michael Andersen describes that coalition in Oregon in this striking passage:

On the other side were AARP of Oregon, which said middle housing makes it easier to age in place; The Street Trust, a transportation group that argued HB 2001 would let more people live near good transit and walkable neighborhoods; 1000 Friends of Oregon, which said the law would advance the state’s long fight against exclusionary zoning; Pablo Alvarez of Lane County NAACP, who said the bill would start to undo some of the ways racism has undermined housing affordability for all; Sunrise PDX, which called energy-efficient housing an essential way to fight climate change; and Portland Public Schools, which described the bill as a long-term way to reduce school segregation.

The issue has also scrambled partisan politics-as-usual. At the federal level, the Obama administration partially took up the cause of removing barriers to housing development, but so has the Trump administration. Issues such as racial desegregation or environmental justice are seen as liberal priorities, but HB 2001 transcended liberal politics, winning two-thirds of both the Democratic and Republican causes in the House, and passed the Senate by a 17-9 vote, including 14 of 18 Democrats and 3 of 8 Republicans. The bill's sponsor was a Portland Democrat, but a small-town Republican took up the mantle as well, as Andersen describes:

"We all have an affordable housing crisis in our areas,” said Rep. Jack Zika, a Redmond Republican who supported the bill before a different committee June 11. “This is not a silver bullet, but will address some of the things that all our constituents need. … We have an opportunity now for first-time homebuyers.”

Odd bedfellows, all reacting to very different facets of a common problem: rigidly exclusive single-family neighborhoods are a fragile way to plan cities that is inadequate to the challenges of a changing world.

Lessons From Oregon's Success

I spoke with Madeline Kovacs of the Sightline Institute, which has been on the forefront of "rabble-rousing" (her term) around housing affordability and other issues in the Pacific Northwest. Kovacs offered this measured take on the likely impact of HB 2001 in and of itself:

“What HB 2001 does most of all is set Oregon on a more sustainable, more equitable path for future growth over the next generation. It is a long-term investment in better housing policy.”

Fourplexes will sprout up on the order of decades, not months. Your city isn't changing as fast as you think. This is not a short-term solution to an affordable housing crisis. Upzoning efforts like HB 2001, or California's abortive attempts such as SB 50, are often framed in terms of the housing crisis and the need for urgent action. This is a useful frame for galvanizing support, but it's also ultimately an insufficient frame, because it leaves you open to the attack that allowing some triplexes here and there won't be a panacea for cost-burdened renters. Not for a place like Oregon, which, per Kovacs, is only adding one new home for every three new households.

A duplex with a rear ADU: 3 modest homes on a lot that would otherwise hold only one. Now do this again, hundreds of times. (Photo by Daniel Herriges)

Legalizing missing-middle forms like ADUs, duplexes, and fourplexes: this is not The Solution™ to a single problem. And those who are baffled by the momentum that such initiatives are enjoying these days are often those who seem hung up on the idea that it either has to be The Solution, or it isn't worthwhile.

Kovacs points out that HB 2001 in Oregon was part of a whole package of complementary housing legislation this session:

We were thrilled to see that housing supply and density bills this session were put forward alongside bills to address other aspects of the housing crisis, from anti-rent-gouging to securing more investment in affordable homes, emergency rent assistance and shelter, among many more. A successful, broad-tent housing coalition will continue to couple policies that can quickly increase the supply of housing with policies that alleviate the acute suffering our housing crunch is causing for our most vulnerable residents.

"It doesn't solve the housing crisis overnight" is no reason not to take the sensible approach of ending blanket apartment bans and ADU bans. This approach is universal—the rare local land-use intervention where state-level action like Oregon just took is actually appropriate—because it removes a distortion that never should have been there in the first place.

Slate’s Grabar emphasizes the potential of Oregon-style blanket upzoning to flatten out the spiky, winner-take-all pattern of neighborhood change and redevelopment. In most cities today, a handful of neighborhoods—usually occupied by lower-income minority residents with less political capital—bear the brunt of a fire hose of development activity while other areas see only a trickle of reinvestment, if anything. Says Grabar:

By upzoning entire cities and states at a time, these efforts could help make sure that it isn’t only low-income neighborhoods of color—the places vulnerable to gentrification and displacement—that become hot spots for development in cities that need more housing.

In other words, that the burden of development is often borne by centrally located, formerly redlined communities of color is a product of the current system, in which social capital and political connections determine who gets to keep their neighborhood the same.

Oregon may have been uniquely situated to blaze a trail on this issue: the state, after all, has a history of both state-level land use controls and openness to urban density, as CityLab's Laura Bliss points out.

But what Oregon has done, and Minneapolis has done, and Seattle and many other cities have taken tentative steps toward, and what more places will hopefully do, is allow every neighborhood the room to breathe and flex a little, by allowing every neighborhood to undergo the next increment of development. This way, the trajectory of development is driven by real market feedback. This is a rational response to a system—the distorted monoculture of rigid single-family zoning—that is experiencing stress from many different directions, because it was never really a resilient or sensible way to arrange our cities in the first place.

(Cover photo: Fourplex in Portland’s Irvington neighborhood. Via Wikimedia Commons.)

Daniel Herriges has been a regular contributor to Strong Towns since 2015 and is a founding member of the Strong Towns movement. He is the co-author of Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis, with Charles Marohn. Daniel now works as the Policy Director at the Parking Reform Network, an organization which seeks to accelerate the reform of harmful parking policies by educating the public about these policies and serving as a connecting hub for advocates and policy makers. Daniel’s work reflects a lifelong fascination with cities and how they work. When he’s not perusing maps (for work or pleasure), he can be found exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods on foot or bicycle. Daniel has lived in Northern California and Southwest Florida, and he now resides back in his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, along with his wife and two children. Daniel has a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota.