"Does Induced Demand Apply to Bike Lanes?" and Other Questions

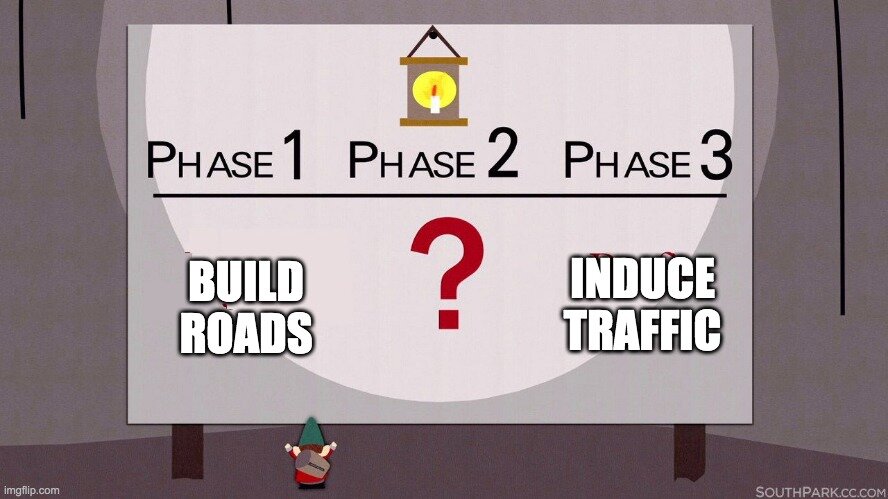

“Induced demand” is one of the stock-in-trade concepts of activists who want to rein in the expansion of roads and highways. The principle goes something like this: The more roads you build, the more people drive on them. That is, a road itself induces the demand to use it.

The key policy implication of this insight is that you can't build your way out of congestion. (You can just bankrupt and gravely damage your city while trying to.)

And yet, the induced demand concept raises more questions than it answers once you start to think about it. For example, why do we only seem to talk about this with regard to roads? Does induced demand apply to other sorts of goods or services? And if not, why are roads so special?

One of my colleagues asked me recently, "Does induced demand also work for bike lanes? If you build more of them, will you get more cyclists?" My answer was, "Yeah, probably, but it's different." Then I had to launch into a longer explanation.

The truth is, this vital concept has gotten muddled somewhere along the way from economics-textbook to public-meeting-comment trope. It's become something that we tend to talk about as almost a mystical force of nature: "If you build more roads, you get more traffic," as though it's Newton's little-known Fourth Law.

This lack of clarity, in turn, has actually sometimes hurt the arguments of those calling for sanity in transportation budgets and expansion plans. We risk opening ourselves up to attack for being imprecise or intellectually lazy or peddling pseudoscience.

Induced demand is not pseudoscience. It's very real, and it's backed up by research. But the term is a bit of a convenient fiction. It conflates multiple different things actually happening to driver behavior. So let's break that down.

What happens when you expand a congested road?

There are actually two different effects that get lumped together under the heading "induced demand."

Effect 1: In the near term, expanding a road causes drivers to alter their travel patterns to use it more.

Effect 2: In the medium to long term, expanding a major road will alter the pattern of development in a city or region, which itself induces more driving.

The first applies to almost any good or service. The second, though, is fairly unique to roads, and we'll talk below about why.

Image via Flickr.

Effect 1: Road building alters travel behavior.

When you expand road capacity—either by widening an existing road or creating a brand new road or connection—you reduce the cost of driving to or through that location. Road users reckon that cost not just in dollars, but in time, aggravation, or inconvenience, all of which might be lessened by the expansion.

Economics tells us that, all else equal, when you reduce the cost of something, people will consume more of it. As far as this goes, "induced demand" is really just "demand," and it's nothing unique to roads.

Substitution: When a road is expanded, some drivers will switch routes to use the newly built road. Some drivers who were avoiding the route at rush hour because of congestion may start to use it at rush hour, rather than earlier or later in the day. Transit users and bicyclists may switch back to driving. Economist Anthony Downs called the above three changes the "triple convergence," and they can very quickly erase many of the gains from added capacity on a specific road. For example, only three years after the widening of Houston's Katy Freeway, rush hour travel times had infamously gotten worse, not better.

The same effect works in reverse. The system finds a new equilibrium, and it happens quickly. Recent history is full of examples where the closure of a high-profile road—whether due to construction, a bridge collapse, or a fire—failed to produce an anticipated traffic nightmare. Travelers simply adjusted their patterns and life went on.

But there are limits to this version of induced (or de-induced) demand, in both directions. The number of people who will adjust their routines in these ways is clearly finite, not infinite.

Addition: Induced demand can also consist of new travel. Some people will make trips they wouldn't have made at all. For example, you might take your kid to visit that zoo all the way across town. You might start dating someone who lives farther away, instead of swiping left. (I have it on good authority from friends in LA that if you live on the Westside, finding out a romantic prospect is in Orange County is a dealbreaker.)

The fight for more bike lanes can get contentious.

Learn how to be a stronger advocate through our course “Picking Your Next Bike Lane Battle.”

Consider the biking question in this light: if you build new protected bike lanes, people will absolutely come out of the woodwork to bike who weren't biking before. It's not that they didn't want to before: they just didn't find it safe or viable. That demand was there but suppressed. Now you've allowed them to do more of what they wanted all along. How could this be bad?

This observation, however, opens up the induced-demand argument to a serious line of criticism: if widening a highway allows people to do things they find valuable that they couldn't do before, like choose from a wider pool of jobs, see more friends, or access more recreational activities, isn't that a good thing? Even if the highway does end up congested again at its higher capacity limit? Isn't the additional travel its users are doing improving their wellbeing?

If you want to make the case that increasing the supply of roads is truly a waste of resources (hint: it is), you need to contend with this argument. To do so, you need to understand the other induced demand effect, the one that truly is (mostly) unique to road building.

Image via Flickr.

Effect 2: Road building alters the development pattern.

Here's where roads really are different.

What makes travel valuable? In the vast majority of cases, it's not the actual act of traveling that we derive value (utility, in economist-speak) from. It's the destination. Travel is merely the cost of reaching a destination.

Learn more!

Check out more of our top content about traffic congestion over at the Strong Towns Action Lab.

When you build a new road or expand a congested one, in the short term it makes some destinations less costly (that is, time consuming or onerous) to reach for some people, while in theory not making any destinations harder to reach than they were before. And that would be the case, if the destinations themselves stayed put. But they don't.

Over time, development in the places that are now better served by road becomes more profitable and attractive. A lot more people are interested in buying a house that's 30 minutes from a major downtown than are interested in buying one that's 50 minutes away. So when you shorten the trip, newly-marketable development follows the new roads. This is especially true with expanding or building new freeways in a growing city: whether we add lanes near downtown or out in the 'burbs, shortening the commute time from the exurbs is a boon to land speculators and builders in those outlying areas.

Meanwhile, the value of close-in locations is depressed, because the competitive advantage of being close to the city has just become a little less. So over time, less development happens in these places, there's less of a market for infill, and in the most depressed neighborhoods, buildings might even be abandoned or demolished. I wrote about this, and visually illustrated it, in “The Other Reason Freeway-Building Hollowed Out America’s Cities.”

These trends make doing far more driving a necessity, not a choice. This is reflected in U.S. national statistics on Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) per capita, which show a steady but dramatic increase throughout the suburban era.

In 1941, your kid might have walked 15 minutes to the neighborhood school. In 2021, you drive your kid 15 minutes to school. Oh, and this isn't your choice: they tore down the old school and replaced it with a parking lot.

In 1961, you might have biked or driven a few blocks to a corner store for milk and eggs. In 2021, you drive 3 miles to Kroger for milk and eggs, and there is no corner store. Has your utility increased? Or are you mostly just consuming more resources?

Road travel is fundamentally different in this respect from other kinds of things you might "induce" demand for, like housing, clothing, food, or entertainment. It's different because doing more of it doesn't mean you're better off.

It's also different from other means of transportation. I promised we’d get back to bike lanes. Bicycle facilities can certainly induce adjacent development (sometimes a whole lot of it) based on their recreational/amenity value, but they don't meaningfully alter the development pattern of an entire region.

What about mass transit? Transit expansion can dramatically alter travel times, and a major rail project can have an enormous effect on land value around its stations. But the effect tapers off quickly once you get outside walking distance of the station.

Because cars are the fastest widely-available means of getting around we have, it's road building, and essentially only road building in our present-day context, that induces the large-scale changes to our cities that force us to drive ever farther. We’re like an addict who needs an ever more powerful dose just to get the same high. The theoretical demand for travel is infinite as long as technology keeps advancing. It can never be satiated. It would be far cheaper to build and live in cities where the people and things we care about are simply nearby to begin with.

For decades, state and federal highway agencies have justified massive projects with traffic forecast models. But a closer look reveals a troubling pattern of exaggeration, manipulation and outright falsification in these models.