Spanish Fork Prioritizes Driver Speed Over Child Safety

In Spanish Fork, Utah, on the corner of Center Street and 900 East, a crossing guard is tasked with the responsibility of ensuring children’s safety twice a day as students at Diamond Fork Middle School cross a dangerous stroad.

In a Twitter thread, Strong Towns member Logan Millsap told the story of how the crossing guard has been warning public officials for over a year that this school crossing is dangerous, and it’s only a matter of time before someone gets seriously hurt or killed.

In October, the crossing guard presented five different design solutions to a Traffic Safety Committee tasked with developing solutions that would help ensure children’s safety at the intersection. Milsap said officials seemed to listen with urgency, assuring the guard and locals present that they were anxious to solve this issue. And yet each of the five solutions was dismissed in that committee meeting, ultimately for the same reason: because it would impede the flow of traffic.

The crossing guard suggested a pedestrian refuge island.

— Logan Millsap (@LoganTMillsap) October 21, 2022

This was dismissed because it would prevent drivers making southbound left turns (again, very few drivers do this). And because it's less convenient for snowplow drivers. pic.twitter.com/3PJIRBQ4I8

East Center Street is a classic stroad, according to Strong Towns president Chuck Marohn. Stroads mix wide lanes designed for high-speed traffic with a multifaceted grouping of people, businesses, and residences. “They're what happens when a street (a place where people interact with businesses and residences, and where wealth is produced) gets combined with a road (a high-speed route between productive places),” Marohn said. “And this combination makes for predictably dangerous environments.”

Before deciding on whether a safer design solution would be implemented, local engineers performed a handful of studies which determined that the five-lane stroad is safe for children to cross with a crossing guard’s assistance. The area is affected by a school speed limit, police force patrol the area to catch speeders regularly, and during a two-day observation, drivers demonstrated a 100% compliance with children in the crossing. Considering these points, and the assumption that children only cross the stroad at two short intervals in the day, the committee decided that the redesign of the stroad would not be worth the investment. They decided that the only necessary changes needed were to have the crossing guard add more cones, perhaps even creating a natural island with them. The crossing guard was also advised to take part in official training so he could properly protect children on the stroad.

Marohn says these recommendations fall short of treating children’s safety as a primary concern. “What is being said is that the number one priority of this intersection is moving through traffic quickly, and everything else has to adapt to that,” said Marohn. “So people have to be better trained, the kids have to be better aware. Everybody else has to accommodate the fact that the number one priority is to move the vehicles quickly through here. The equivalent (of these safety studies) is that we have a room with knives and matches and poison and we watch some kids play in it for, you know, a day and nobody gets hurt. And then we conclude that, well, I guess this room is 100% safe.”

Marohn said that if the priority were truly the safety of children crossing, the stroad would be redesigned to ensure traffic speed is reduced.

“It doesn't take a 5% noncompliance rate, or 10% noncompliance rate, or a 50% noncompliance rate to have a tragedy,” said Marohn. “It just takes 1%. Which is not observable in a two-hour or a two-week or a two-month study.”

Marohn said relying on police enforcement and speed signals won’t control traffic speed, either. The typical driver does not select their speed based on the posted speed limit. Rather, they rely on visual and other physical cues that intuitively communicate to them how fast it feels safe to go on a given roadway. The only way to truly make the stroad safe is to redesign it.

This is one of the saddest situations,” said Edward Erfurt, urban designer and Strong Towns director of community action. “The city has prioritized driver speed over people’s safety.”

Millsap’s Twitter thread is filled with comments of frustration and drawn examples of how simple it would be for the Traffic Safety Committee to make design changes for a safer street. Erfurt said, “There are several simple design elements that could easily be implemented in a day by the city’s public works department, with the direction of the city engineer.”

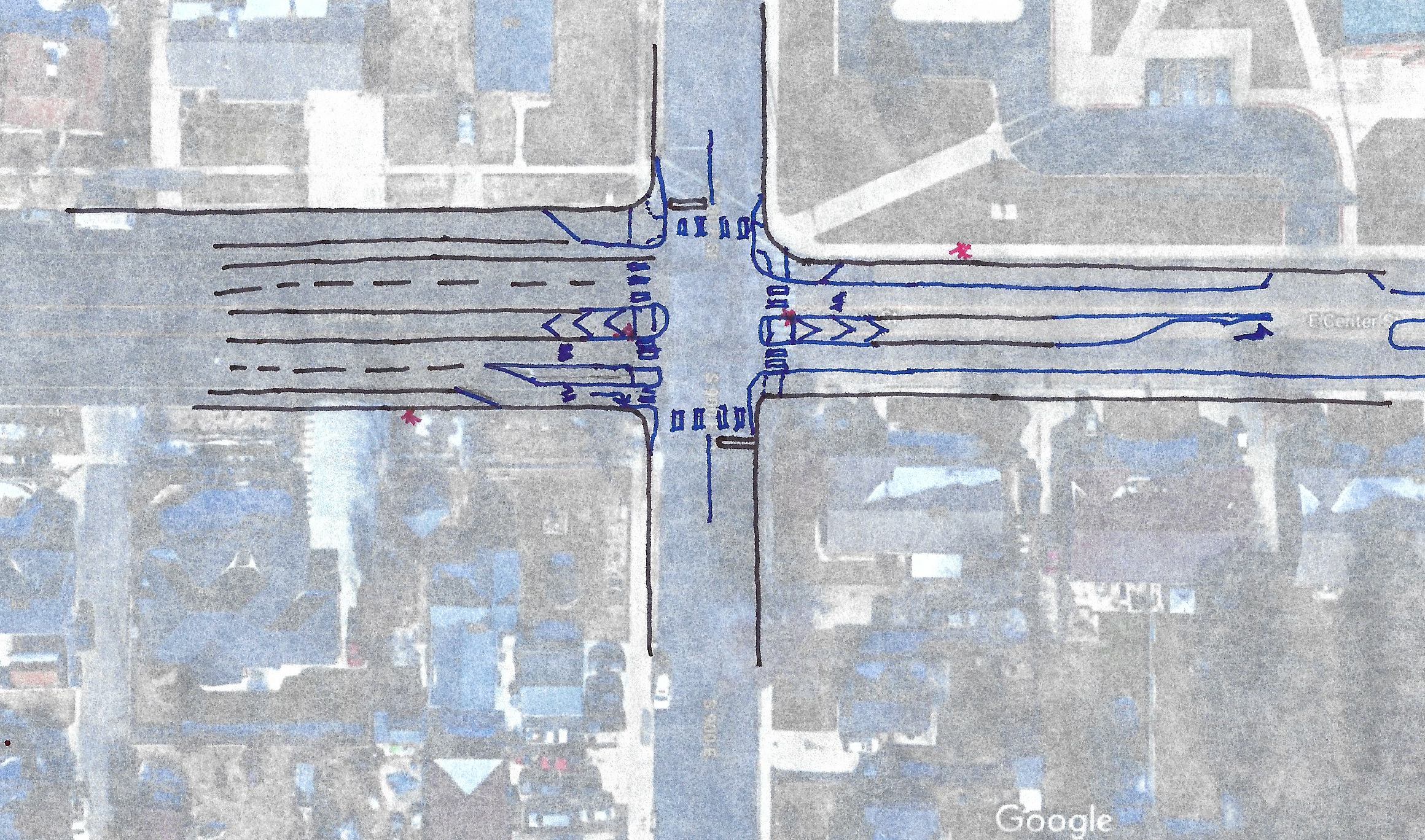

As an example, Erfurt put together the design below. He noted that all suggestions have the ability to be quick, easy, and temporary until permanent solutions can be constructed. This design highlights painting high-visibility crosswalks, adding “YIELD to Pedestrians'' signage, creating narrow street lanes by painting parking lanes, adding curb extensions on corners, and painting pedestrian refuge islands within existing center-turn lanes.

The Traffic Safety Committee said that if traffic became noncompliant and someone were to get hurt or killed, they would consider permanently redesigning the stroad. But, until the stroad reaches that point of danger, there is no evidence in their studies that it is truly dangerous.

Milsap offered a blunt interpretation of this criterion in his original Twitter thread, invoking the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), the manual used by traffic engineers to set crosswalk standards: “The priests of MUTCD demand blood sacrifice before they’re willing to act. When a child is hit or killed here it cannot be called an accident.”

“We're playing a game of chance,” said Marohn. “And it's very possible that we could go a month, a year, a decade, with no one getting hurt or killed. That is not like a success story. That is just luck working out your way.”

Seairra Jones serves as the Lead Story Producer for Strong Towns. In the past, she's worked as a freelance journalist and videographer for a number of different organizations. She currently resides between small-town Illinois and the rural Midwest with her husband, where they help manage a family homestead. When Seairra isn’t focusing on how to make our towns stronger, you can find her outside working on the farm, writing fictional tales in a coffee shop, or reading in a hammock.