The Reckless Driver Narrative Is Reckless. Stop Spreading It.

(Source: Unsplash.)

The Reckless Driver narrative is out of control. The latest salvo comes from a report produced by AAA’s Foundation for Traffic Safety, which documents self-reported risky behavior and compares that to the amount of time people spent driving during the pandemic. The conclusion is that riskier people spend more time driving than safer people, which is thus a contributing factor to why deaths have increased while driving has gone down.

Of course, this is being picked up and run by media and advocates eager to blame broken and deviant humans for their shameful behavior, a narrative that feeds into cultural tensions in a way that generates clicks, but not thought or substantive action.

I hate this narrative, not only because it is wrong but because it empowers a status quo engineering and design approach that resists change.

Stop for a moment and recognize an uncomfortable truth about something as reckless as drunk driving: Almost everyone who drives under the influence of alcohol—people who are driving impaired—reach their destination without crashing into anyone or anything. As I wrote in Confessions of a Recovering Engineer:

Yet, we are fooling ourselves if we fail to recognize that only the smallest fraction of impaired trips ever ends in tragedy, let alone some type of sanction.

Almost every person who has driven impaired, be it from alcohol, illegal drugs, legal prescriptions, lack of sleep, caffeine, or multiple other things that limit a driver’s capacity to engage fully while operating a vehicle, arrives at their destination with no problem. It is extremely rare that this kind of bad decision results in someone’s death. Extremely rare.

In other words, there are more factors here than just recklessness—way more—but we are laser focused on the broken human. For critical thinkers, this should be tripping all kinds of mental alarms.

The AAA study reports that half of drivers who increased their driving during the pandemic (124 respondents) self-reported engaging in the risky behavior of texting while driving in the last 30 days. That’s really bad and it’s really dangerous. People should not text and drive.

Yet, a third of those who drove the same or less during the pandemic (2,764 respondents) self-reported that they also texted while driving during the last thirty days. That’s 910 people in the “less reckless” category who texted while driving and ostensibly made it alive to where they were going.

Tens of millions of Americans engage in the risky behavior of texting while driving each day and nothing happens to them. Their increased risk does not result in tragedy. What AAA wants us to believe is that a reportedly slight shift in the number of people engaging in this high-risk behavior is causing dramatic increases in deaths. That doesn’t make sense.

It almost always takes more than reckless behavior to cause a crash to occur. It takes something else, something we can broadly categorize as a dangerous encounter. A million people might text and drive over the next hour and one or two of them will be in a crash where someone dies as a result. The thing that will distinguish the 0.01% of trips that results in a death is not recklessness; it is something else, some random and likely unexpected occurrence that led to the crash.

A person unexpectedly turns across traffic. A person pulls out when it wasn’t expected. Someone brakes when the driver behind them isn't focusing. There are countless random situations for a crash to be catalyzed.

Over-simplified for the sake of this discussion, we can think of this as an equation with two variables: reckless driving and random, dangerous encounters.

Traffic Deaths = (Rate of Reckless Driving) x (Number of Dangerous Encounters)

Yes, we will get more deaths if we increase reckless driving—I’ve never argued otherwise—but as the AAA report points out, self-reported reckless driving is endemic. It always has been. Even the people they suggest are in a lower risk category are talking on their phone, texting, speeding, running red lights, and driving impaired at shocking rates. The pandemic has not dramatically changed this.

What has changed dramatically is the number of dangerous encounters, the number of times that the reckless driver is in a high-risk situation. Before the pandemic, most daily trips were made during periods of high congestion, where the danger inherent in our roadway designs was masked by the slow, stop-and-go speeds of Level of Service D and F. Now, with pandemic conditions and then expanded work-from-home moderating congestion levels, most trips are made at unsafe speeds in environments filled with randomness. The pandemic has dramatically increased the number of dangerous encounters a typical driver experiences.

Focusing on reckless driving is obsessing over the smallest fraction of the underlying cause, but it fits a narrative that engineers, transportation planners, and traffic safety officials are more comfortable with, one that puts the blame on others, primarily the Reckless Driver.

And, in terms of the AAA report specifically, is the self-reported measurement of reckless driving a measurement of recklessness or a measurement of driving? The assumption of those doing the study is that this self-reported data constitutes people acknowledging an increase in reckless behavior. It’s far more likely they are simply reporting an increase in opportunity to be reckless. These people are driving more and so they have more opportunity to experience a reckless instance. If the reporting period wasn’t “the past thirty days” but “the past year,” it is likely that nearly 100% of drivers would report engaging in behavior deemed reckless.

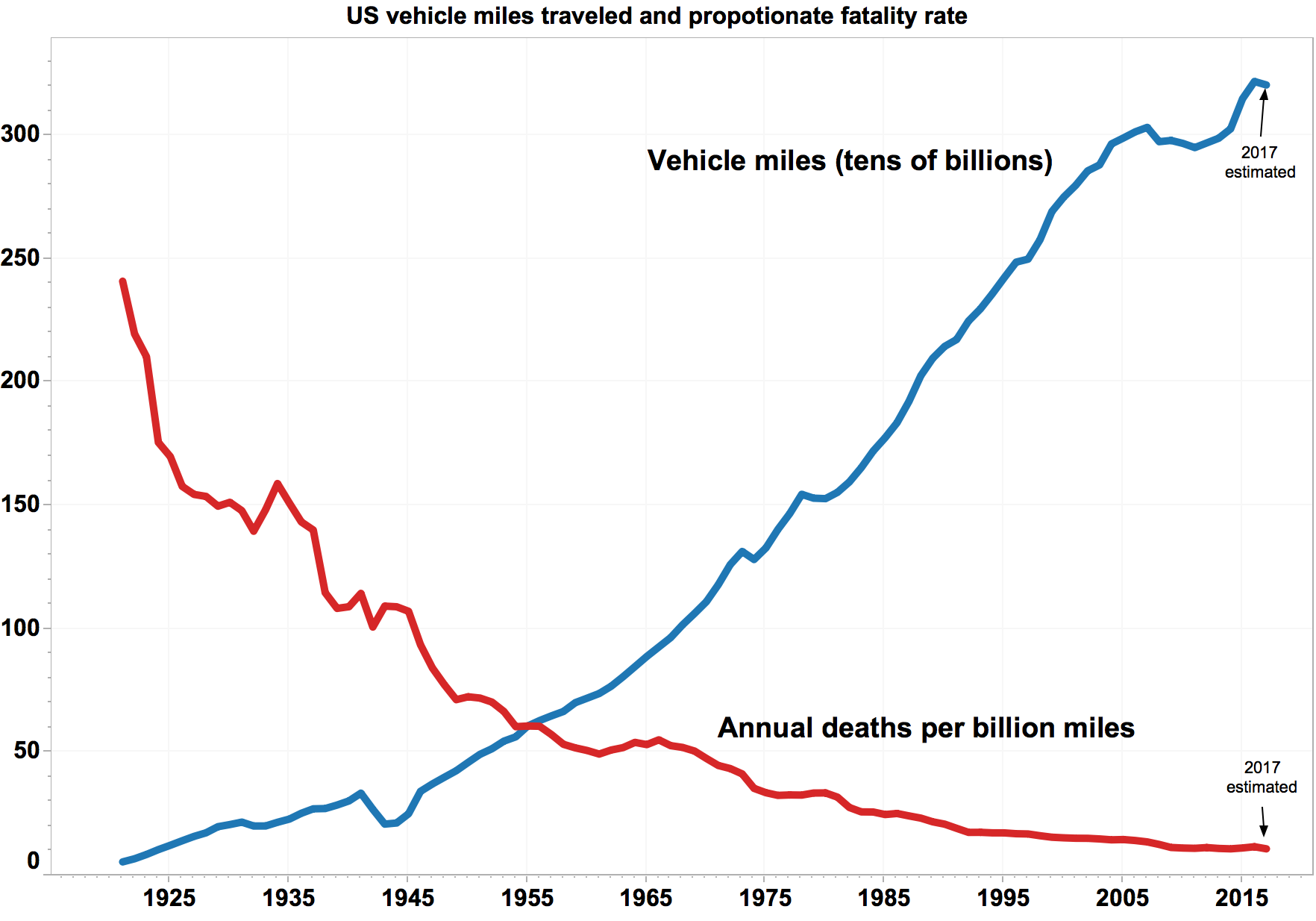

For decades, we’ve been doing things to bring down death rates on roadways. We widen lanes, add recovery areas, and build clear zones, using expanded engineering budgets to ostensibly make our roads safer to travel. We require seatbelts and airbags. We increase enforcement and do public service campaigns. We advocate for complete streets and other ways to safely accommodate pedestrians into our design.

And then we step back and take note of our success because death rates have been going down. If you’re in this business, you draw a straight line between your own actions to improve safety and these dramatic results.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Those focused on more padding and armor on our vehicles and roadways, more enforcement, and addressing the flawed nature of (other) humans take comfort in drawing that connection, but I don’t. I think they have it completely wrong. I think the drop in fatality rate per mile traveled is more easily correlated with another statistic: traffic congestion.

(Source: ResearchGate.)

As congestion goes up, deadly crashes go down. All that extra engineering, enforcement, public information campaigns, and the like is negated and unnecessary because you can’t drive fast when there is a car stopped in front of you. Statistically, you won’t be in a high number of really dangerous encounters when you’re in stop-and-go traffic.

We see less deaths over time because congestion has gotten worse, not because we’re building things dramatically safer. And the proof is that, once the pandemic removed all that congestion, deaths went up.

And deaths have gone up not because drivers are way more reckless but because the way we design our arterials, collectors, and local streets is ridiculously dangerous. And now, without congestion, that danger is being more fully realized.

Last week, we received this comment on the Reckless Driver topic:

...you are focusing on an abstract idea, making the same mistake that you are accusing the media of making.

Of course engineering is important. But it clearly is not the only thing that matters. When 1/3 of all crash deaths in the US involve the use of alcohol, human behavior and attitudes and training are important.

Your language implied to me that you do not think that behavior and attitudes matter. Strong Towns often has a simplistic approach to these critical issues.

The Reckless Driver narrative is so seductively easy to believe. We see crashes happening, we know people are being injured and killed, and a lot of those incidents involve people who were doing something reckless. They were reckless, but—as uncomfortable as it might be to acknowledge—they weren’t doing anything out of the ordinary.

And that’s the point. Of course, behaviors and attitudes matter, but humans are flawed. We are going to mess things up, make mistakes, misjudge things, and some (a shockingly high percentage that, at some point, includes each and every one of us) will be a Reckless Driver. That has always been true.

Our design approach assumes the opposite, putting millions of people in dangerous situations where one random “mistake” results in life-altering tragedy. That is what is truly reckless. Congestion merely mitigates that danger.

If you care about traffic safety, if you care about human life, you need to join me in pushing back on the Reckless Driver narrative. It emboldens those who would gladly spend billions of dollars making our streets less safe and our communities worse off. It is an intellectual dead end. Don’t be seduced by it.

If we want strong towns, if we want safe and productive streets, we have to focus on the deadly design of our public spaces and not be distracted by the Reckless Driver scapegoating that industry leaders want us to believe.

Our transportation system is too costly. Not only in dollars, but in human lives.

It’s time to put an end to it and change our unproductive, dangerous streets. If you think this message is important and want to help it spread, then join the movement. Become a Strong Towns member today.

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.