The Best Books I Read in 2023

This is the 10th consecutive year in which I’ve published my end-of-the-year book list. I highlight my favorites from the year and then give you the entire reading list. I enjoy doing this—it is nice to look back and take stock—but I’ve also found it to be surprisingly controversial, in an internet kind of way. Chill out, people!

Sometimes people are disappointed that I don’t read more planning, engineering, or urbanism books. I’m sorry, but they rarely interest me. The genre is mostly people saying the same thing, in variations of the same way. If you want my list of recommended books for Strong Towns thinking, we made that available years ago. This is the actual list of books that I read in the past year.

I read what interests me. That means I shift topics broadly but sometimes go really deep into something I’m fascinated with. (One year I read half a dozen books or so on consciousness, for example.) I get through about a book a week, half of them in audio format and the other half on Kindle or by evening lamplight (I read mostly before I fall asleep). Oh, and I save all my fiction for family vacations and end-of-year baking; I’m mostly a nonfiction guy.

Neither I nor Strong Towns get any kickbacks or compensation of any sort for these recommendations. That’s also been a source of stress with this list—friends who write books and are upset with me that they don’t make the top five—but, again, chill out. The older I get, the more I’ve found myself unwilling to waste time on books that I don’t find meaningful. Some of the books on this year’s master list were ones I abandoned halfway through, but the ones I highlight below are gold.

The One: How an Ancient Idea Holds the Future of Physics by Heinrich Päs

Think of an old-time movie projector. The film passes over the lamp and images are projected on the screen. The images tell a story, often beautiful and complex. If we’re asked to describe this, we’d probably talk about the film creating an image. That is not wrong, but it’s not exactly correct, either.

What is really happening is that light is projected onto the wall and the film, in order to create the images, removes some of that light. Part of the light is redacted. It is that subtraction of a part of the light that creates the images we see.

What is the totality of reality—what is all the light—and how does that compare to the reality that we see and experience? What 20th-century physics has confirmed for us is just how little of true reality we experience. We are images living in a construct with much (most) of the light redacted. How much more is there, and what is meant by being there? Is it a reality we can interact with if we could perceive or infer it, or is it beyond our capacity to reach?

This book was two parts physics, one part theology, and one part a beautiful reflection on all that connects us. I took my time with it and spent many restless nights thinking about the implications. Highly recommended, even for those with only a passing interest in physics.

The End of the World is Just the Beginning: Mapping the Collapse of Globalization by Peter Zeihan

This book is Strong Towns for globalization. The thesis is very similar and the narrative arc follows a familiar path.

The post-war economic order is neither destiny nor is it a normal condition. It is a historical anomaly, one that was wonderful while it lasted, but which is financially (environmentally, culturally, politically, etc.) unsustainable. All things unsustainable ultimately cannot be sustained. Zeihan does a compelling job of showing how it’s ending and giving his vision for what will come next.

I found this book so compelling that I purchased it for a bunch of people very close to me, people whom I admire, respect, and frequently look to for guidance. These are people deep into Strong Towns thinking. Almost all of them seemed to be so annoyed with Zeihan’s predictions for the future that they categorically rejected the core insights of the book. Read the book, but don’t do that.

As Nassim Taleb, the Patron Saint of Strong Towns Thinking, often says: I don’t need to be able to predict which truck will collapse the fragile bridge to say with high confidence that the bridge is going to collapse. Globalization relied on a series of one-time conditions that not only no longer exist, they can’t be naturally recreated. And they are over. Great book.

The Doomsday Calculation: How an Equation that Predicts the Future Is Transforming Everything We Know About Life and the Universe by William Poundstone

If Zeihan’s book on the end of globalization isn’t challenging enough, then Poundstone’s take on Bayesian statistics will be a trip. I’ve been running into applications of Bayes theorem and really wanted to understand it better. I’m not sure I have, but let me try to explain the book this way.

Let’s say that we put all humans that ever existed, and ever will exist, onto four school buses (these are big buses). We could sort them equally into the four buses, but Bayes would have us sort them based on how close they are to the beginning and the end of human existence.

If we say humans will be around x number of years, from beginning to extinction, then each bus represents one-fourth of the time period. The people in the first bus are the earliest humans. The people in the last bus are the ones closest to the end; in fact, some will be the very last humans. So, the question is, what bus are we on?

The first bus will be almost empty. There were hundreds of thousands of years of humans being around when there were very few of them in existence. The second bus is also likely to have a lot of room to move about. Humans have been around a long time; it took until the early 1800s for the global population to exceed one billion. So, not knowing when the end is, timewise, we can be confident in one thing: there will be a lot more people in the last two buses than the first two, a lot more people born after the midpoint than before it.

And, if we’re confident about that, we can be confident about this related fact: any random human, including you and me, is statistically more likely to be in the last two buses than the first two. In fact, when it comes to humans, we are way more likely, statistically speaking, to be in the very last bus.

If this logic fascinates you, you will enjoy reading this book and thinking through the implications.

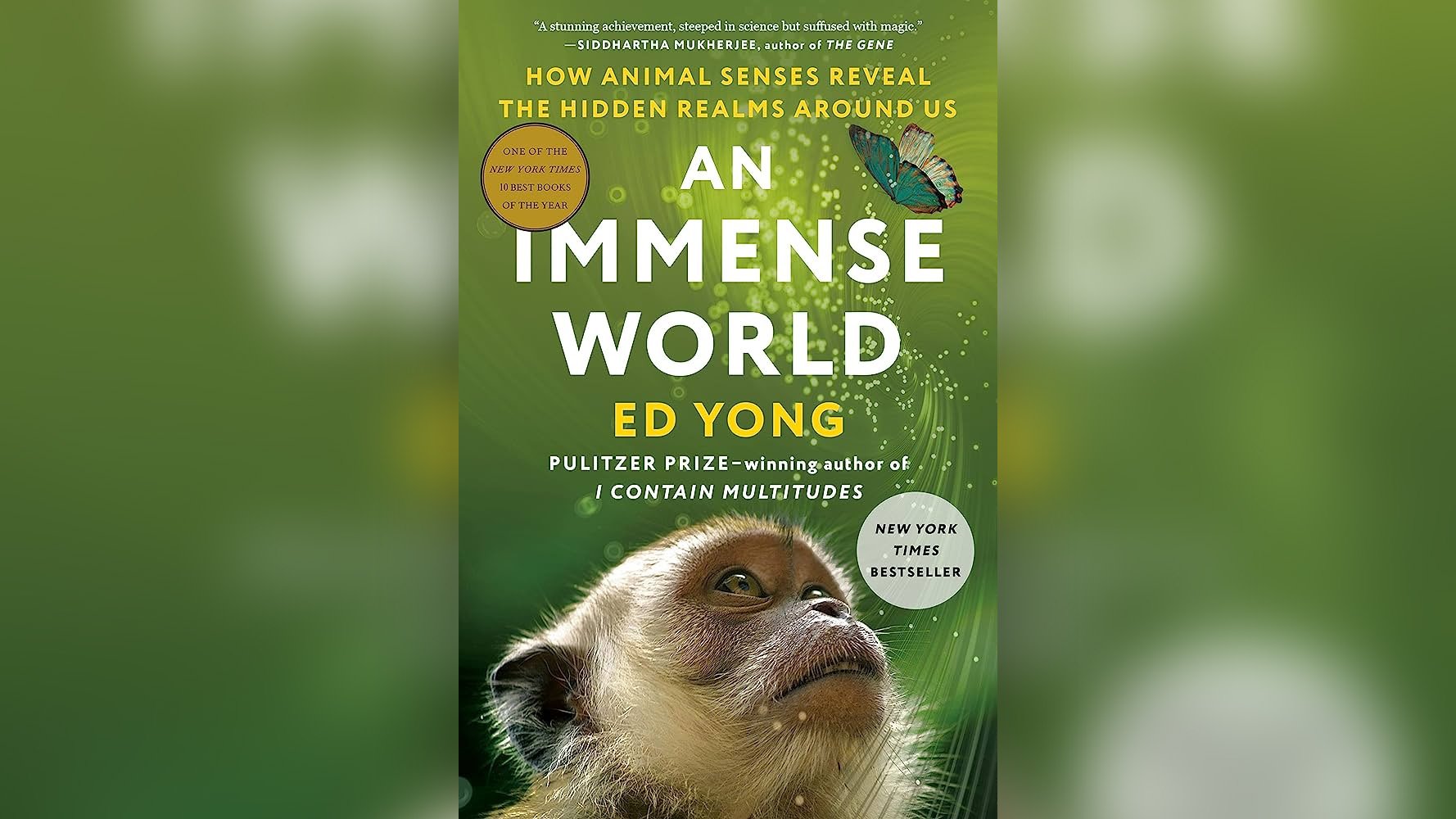

An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us by Ed Yong

I mentioned the film projector in my review of The One by Heinrich Päs, how our existence is not the building up of many things, but the removal of many things to create space we understand. In An Immense World, Ed Yong provides very real and humbling examples of how animals are able to perceive and experience realities we are completely ignorant of.

There are many examples that stick with me nearly six months after reading the book. Flies that seem to navigate in random, almost drunken, kind of flight patterns are surfing subtle shifts in air temperature to aid in their flight. Many birds are not only able to sense shifts in magnetic patterns, making the Earth’s magnetic fields a giant compass, but they see different colors than we do, perceiving a light spectrum that gives them colors like plurple (ultraviolet plus purple). Fish swimming in schools are able to use electrical pulses to communicate with each other as they move.

Perhaps the most humbling, and depressing, was the section on bird songs. Anyone who has sat and appreciated the beautiful music that birds make might be saddened to recognize that we perceive but a small fraction of the complexity of these songs. Humans are incapable of hearing the subtle shifts in tone that birds communicate. What may sound to us like a simple, yet beautiful, note is—in reality—a complex movement of sound around that note. It’s as if they are painting like Michelangelo and our eyes are only able to perceive a child’s crayon drawing. We’re missing so much.

Now take the lack of perception and recognize that it is everywhere. The creatures around us literally see, hear, smell, taste, perceive, receive, and interact with the same world, but in a radically different way than we do. Now, go back and read The One again and live with the truth that there is so much more. So. Much. More.

Ishmael: A Novel by Daniel Quinn

My friend, Joe Minicozzi, recommended this book to me on a couple of occasions. I finally got around to it and loved it. The premise is somewhat cheesy—a highly intelligent gorilla that is able to communicate with perceptive people through telepathy—and I’ve seen that notion ridiculed in places. Yet, it is merely a device to get to the ideas, which are worth getting to.

There was a lot about religion here that I wasn’t prepared to hear, including an interpretation of the Adam and Eve story that rhymes with ones I’ve encountered before, but in a radically different way. I enjoyed the way the book challenged me, which was much of the point.

I am haunted with one of Ishmael’s concluding thoughts and I share it here out of context and without the necessary pretext. (Please skip if you are going to read the book and then come back and discuss.) What if we had put, or did put, our time and energy into nurturing the evolution of the next species to human-level intelligence? What if gorillas, whales, wolves, bees, or any number of species grew to be hyper-intelligent in the ways we are? How much more powerful, and beneficial, than an AI, for example, would that be?

AI is, after all, humans trying to create superhuman intelligence by speeding up evolution. What if instead we turned our attention to the species around us that were already highly intelligent and just allowed them—perhaps even protected and nurtured them—to evolve to that next level? I’m impressed with the sheer mimicry power of AI, but we really don’t need superhumans as much as we need intelligence with different perspectives, sensitivities, and awareness.

Honorable Mention:

American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin

I read this one before going to the movie. If you haven’t seen the movie, it was my favorite of the year (by far) and I highly recommend it. The book provided a lot of depth that gave it even more meaning.

Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon by Michael Lewis

I enjoy Michael Lewis’s writing and this was no exception. A lot of people I respect criticized Lewis for not making Sam Bankman-Fried into a villain character, but I appreciated that aspect of the story. Few people who do bad things are pure villains. What was most interesting to me was how people threw money at SBF—billions of dollars—and how it didn’t seem to change the core of who he was (an awkward, geeky, idealistic, hedonistic, but not really materialistic person). There is way more than “bad guy steals money from the greedy, the rich, and the stupid” to this story and I’m grateful Lewis captured some of that.

Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar by Tom Holland

After reading multiple books by Tom Holland over the years, I’ve become a fan of The Rest is History podcast without connecting one of the hosts with the books. When Holland’s latest book, PAX, came out in October, I decided to go back and read the second in the series before digging into the new one. PAX is on my Christmas list.

The Indifferent Stars Above: The Harrowing Saga of the Donner Party by Daniel James Brown

This was a random Twitter recommendation by someone who knows my tastes in books. Just a solid tale from beginning to end. I listened to it during my travel season this fall and it made a day of planes, cars, and shuttles go by very quickly.

If you’d like to see all of the books I read this year, do make sure to check out my list on Pinterest. You can also go back and see my recommendations for 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, and 2014.

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.