Governor Parson Proposes $859 Million Driving Subsidy

This article was originally published on nextSTL, and is shared here with permission. All images for this piece were provided by the author, unless otherwise indicated.

My, my how times have changed. In 2015, fresh off the heels of the proposed sales tax increase for transportation (mostly for highways) going down in flames in August of 2014, the Missouri Department of Transportation (MoDOT) came up with the Missouri 325 plan. It was an austerity plan based on only $325 million in state funding for road construction.

Many hands were rung at the prospect that the state might not have enough funding to match the potential amount it could get from the Federal government. Since then, in 2018 a gas tax increase put before voters also went down in flames. For a few years it appeared the state’s addiction to road building might be held in check. Perhaps we could discuss whether the state’s bloated and insolvent road network needed reform.

In 2019, though a $100 million driving subsidy was proposed to help close the gap with general revenue funds. In the end the Missouri Legislature passed $50 million. In 2020, the Missouri Legislature passed and Governor Mike Parson signed a 12.5 cent gas tax increase, phased in over five years. When fully phased in, it would raise about $500 million annually. It was criticized as being the largest tax increase in Missouri history. The phase in kept it under the threshold of the Hancock amendment, so it didn’t have to go before voters. Then Congress passed the President’s infrastructure bill, adding more potential funds. You might think all that would be the fix even the most strung-out road-building addict was jonesing for, however…

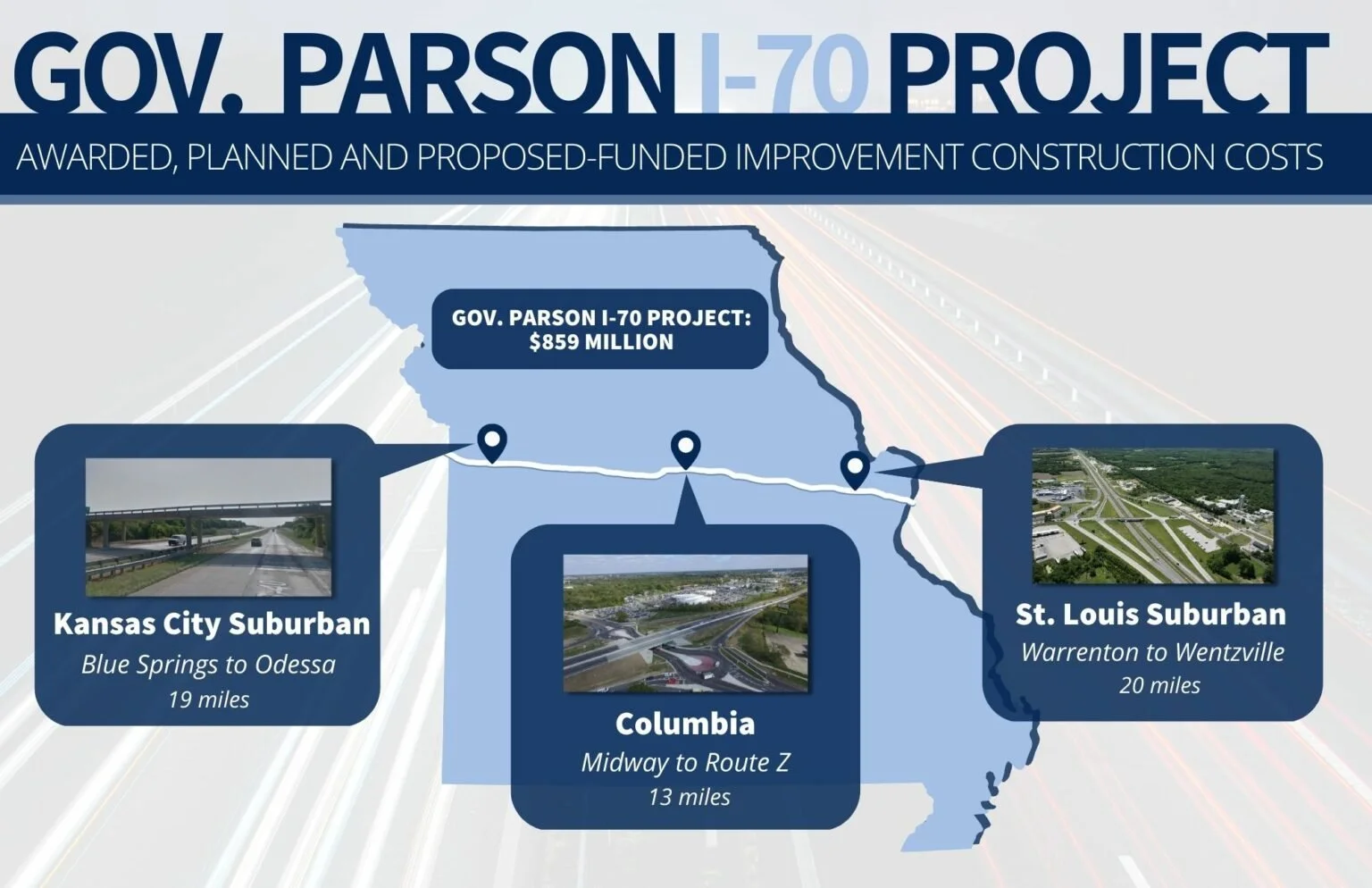

At Governor Parson’s State of the State address on January 18, he proposed a plan to subsidize driving with $859 million in general revenue funds to rebuild and add a third lane in each direction to I-70 in three segments, totaling 52 miles.

For years, congestion, traffic accidents, and delays have become serious issues for commuters on I-70. Not only are we concerned for motorist safety, these inefficiencies are costly to our state’s economy,” Governor Parson said. “To those who say we can’t afford it, I say we can’t afford not to. This is a once in a lifetime opportunity, and the time is now.

—Gov. Parson 2023 State of the State Address

The governor is stuck on a mid-20th-century economic model wherein connecting cities via interstates provides big economic returns. Connecting St. Louis and Kansas City and points between and beyond had a high return on investment, but there are diminishing returns to scale. What we’ve seen lately is that added highway capacity mostly spreads out places, enabling longer commutes. These spread-out places don’t have enough economic activity to cover the long-term costs of the infrastructure serving them. Doubly bad is that extra driving to accomplish the same things sends more wealth out of the state via the fuel consumed.

Governor Parson cites congestion as a motivator. We’ve seen time and again that adding capacity mainly induces demand. It’s the “one more lane will fix it” mindset. Combating congestion could be accomplished by better pricing the use of the highway. Right now, it’s like a Soviet bread line, or perhaps a more contemporary analogy would be the line outside Ben and Jerry’s on their free ice cream day. In 2014, MoDOT studied tolling I-70 from Wentzville to Independence to pay for the estimated $2 billion ($2.5 billion in today’s dollars) cost to redo I-70.

Based on the current traffic, it is likely that a trip across the state on I-70 would cost $20-$30 per car ($40-$90 for trucks) to generate enough funds to pay for the $2 billion project.

Let’s compare the $30 toll to the amount of gas taxes paid to traverse the same route. $30 for 200 miles is 15 cents a mile. 200 miles at 20 miles per gallon, times $0.22 for the state fuel tax, comes out to $2.20 per 200 miles—or 1.1 cents per mile. Ouch, amazing what the true cost is (well ignoring the cost to society of the negative externalities) and how underpriced driving is. No wonder the state is in such a financial hole.

1970: One more lane will fix it.

— 21st Century City 🏗🚲🚉🏙 (@urbanthoughts11) November 4, 2019

1980: One more lane will fix it.

1990: One more lane will fix it.

2000: One more lane will fix it.

2010: One more lane will fix it.

2020: ?pic.twitter.com/NjS1IPORG2

via @avelezig

The governor cites safety as a motivator. As we’ve seen during the pandemic, wide open roads encouraged more reckless driving and more wrecks. Congestion actually helps safety, so if the widening leads to longer periods of low congestion, the highway will be less safe. What is actually safer is putting things closer together so places can be reached at slower speeds by car (avoiding a highway altogether) or, better yet, by other, safer modes of transportation.

Governor Parson has also mentioned delays. The dollar-value-of-time-saved-by-a-highway-widening trope is trotted out in every highway proposal. As we’ve seen time and time again, that time saved is thrown away by spreading places out more.

Parson cites the inefficiency of current conditions and its negative impact on the state’s economy as a motivator. What is inefficient is burdening the state with more infrastructure liabilities serving low productivity land uses. What is inefficient is moving people via car more often and longer distances to accomplish the same things. Both in terms of energy and dollars. The state’s endless commitment to driving is damaging Missouri’s economy. The wealth spent on fuel leaves the state. Luckily, we have some auto manufacturing here, but still, a lot of the money spent on vehicles leaves the state. The cost of it all crowds out spending on other life needs, of which a higher proportion stays in the local economy. What would increase efficiency is increasing the number of trips Missourians could take by cheaper means. And then there’s also the cost in lives and property from car crashes.

We’ll probably see something that looks like economic growth enabled by the highway widening on the outskirts of the St. Louis and Kansas City metros. If you draw a small circle around those areas, sure, it’s growth. But the “growth” mostly comes at the expense of already existing places: build, abandon, build, abandon. What the state is doing is picking winners and losers.

The governor cites the state’s flush coffers as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to accomplish this. Given the climate crisis, the state’s flush coffers should be the opportunity to reduce Missourians’ dependence on driving.

The governor’s proposal would use general revenue to pay for it. He proposed nothing for transit, intercity passenger rail or bus, freight rail (replace semis on the highway), airports, international air travel, etc. For the most part in the past, at the state level at least (the Federal highway trust fund has been bailed out by general revenue for many years), highway spending has come from fuel taxes. That provided some feedback to drivers using the roads paying for them. This subsidy perturbs that feedback mechanism. Also, out-of-state users of the highway will contribute nothing to this expenditure.

The need to redo I-70 has been long identified as a priority, yet the “big” gas tax increase going into effect isn’t enough to pay for it, nor all the other highway liabilities the state has amassed. We already knew that, of course. The 21st Century Missouri Transportation System Task Force in 2018 concluded that the sate needed $825 million (a billion in today’s dollars) in additional annual funding.

The financial shortfall is an indictment of the state’s irresponsibility to account for its liabilities. The maintenance and eventual rebuild of roads and bridges is quite predictable. Instead of putting money away to cover those liabilities over time, the state runs the system like an unfunded pension—making a promise to provide the benefit in perpetuity, but not having the money to back up the promise, meanwhile people become dependent. Imagine instead if with each new road, bridge, or widening, money had to be set aside, so when the bill comes due, there would be money there. The trouble is that would have meant higher taxes or less road building in the past. Well, now we’re left holding the bag on a lot of liabilities previous generations have given us.

Governor Parson needs to get his head out of the past. Moving people and goods by the most expensive, dangerous, and environmentally damaging mode is exactly the wrong idea for our time. The use of general revenue that could go to other things to subsidize driving is simply irresponsible.

Richard Bose is an electrical engineer by profession, and is the interim senior editor at nextSTL, as well as a contributor to the site since 2011. He earned a BA in Physics and Economics and an MSEE from Washington University in St. Louis. He is on the board of the Skinker DeBaliviere Community Housing Corporation. He is a transplant from Central Illinois and has called St. Louis home since 1998. He can be found on Twitter @Stlunite and contacted at richard@nextstl.com.

Car companies have been talking about making cars a third place for years, and the concept has been engrained in North American culture for even longer. But can cars actually function as a third place? More importantly, should they?