Small Is Beautiful: This Developer Targets a Neglected Housing Market

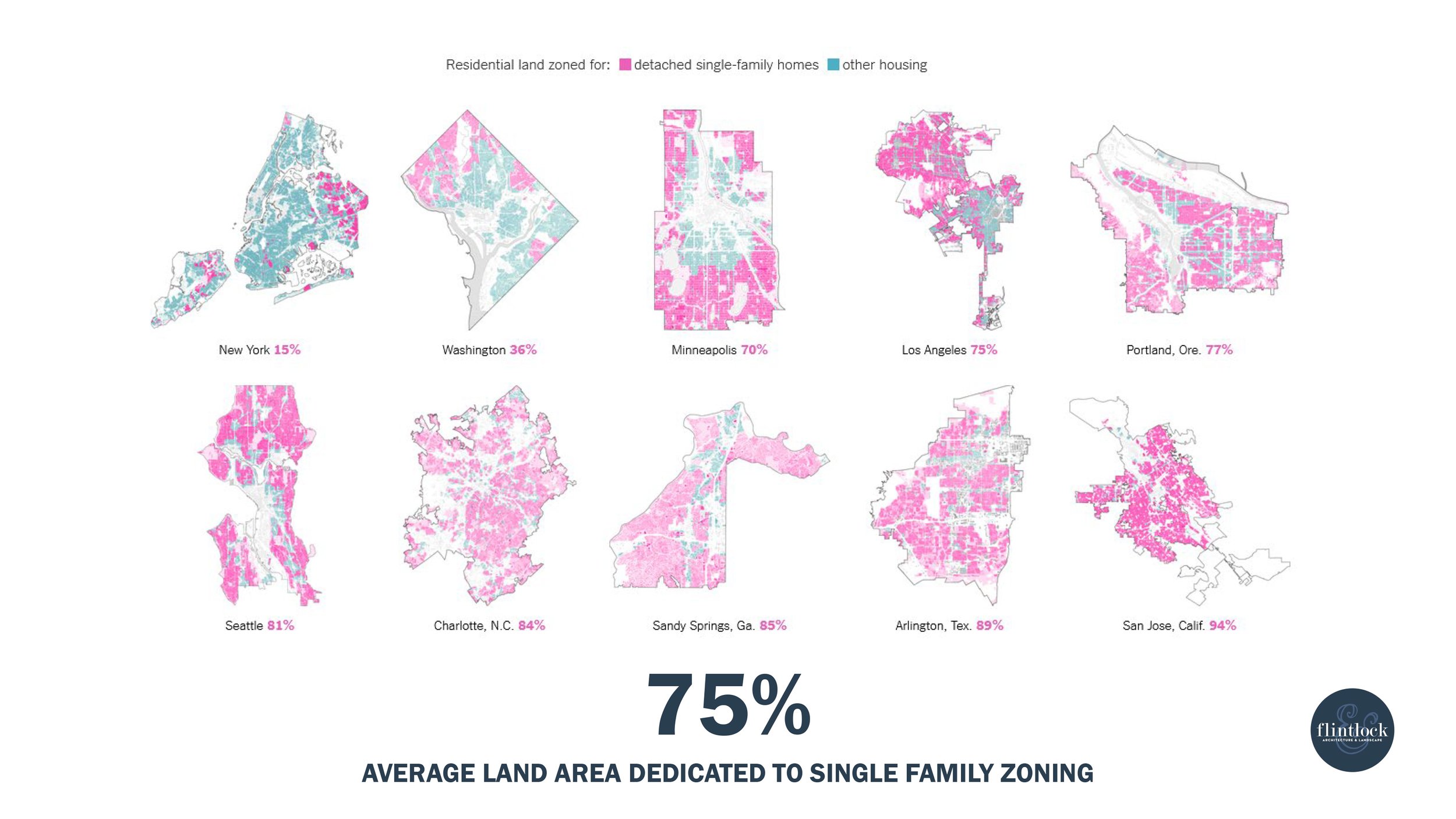

(Source: Flintlock LAB/Alli Thurmond Quinlan.)

Twenty-nine percent of all U.S. households have just one person, according to U.S. Census data. Another 35% have only two people. Yet, despite the fact that a combined 64% of buyers aren’t demanding the extra space, over 88% of all new homes have three bedrooms or more. There are many culprits for this mismatch—zoning, financial structures, an unimaginative industry—but the result is that the entry level for buyers and renters is increasingly unattainable.

Alli Thurmond Quinlan, Principal Architect with Flintlock LAB, presented these startling stats at the recent Strong Towns National Gathering, plus the fact that 75% of buildable land in American cities is zoned for single-family housing only. Quinlan is a developer in Fayetteville, Arkansas, and saw a business opportunity in a neglected market.

“There are good reasons to build small, and you can make small homes nice,” says Quinlan. She says many factors have converged to make the “minimum viable product” in the housing market an oversized single-family home on a quarter-acre lot, and the results are exacerbating the housing crisis.

Flintlock LAB has done several small-scale infill developments that have found eager buyers. And they’ve done it with creative projects that have been popular and profitable.

One version is what Quinlan calls a “stealth fourplex.” The elevation facing the street looks like a traditional single-family home, but the structure goes deep and accommodates four units on its lot, with an identical structure next door. This brought eight appealing units to an infill space that could have been used for two large houses. In another development, a series of small cottages line a hill that converges into a park. While the lots are small, residents have easy access to an appealing public space on the block.

Designing smaller properties does bring special challenges. “You can't just shrink every single room slightly,” quips Quinlan. But you don’t have to compromise on many attributes buyers are seeking, so she strives to design homes that can accommodate full-size furniture, as well as a dining solution that works for guests. “That means our layouts have to be super efficient, getting the most out of every single square inch … We're doing electric hot water heaters so they can tuck under stairs, we have lots of little closets tucked into places,” says Quinlan.

These projects tend to have higher costs per square foot than other properties on the local market. Quinlan says that figure represents “a mentality that we've really tried to shift” regarding small houses. “Price per square foot is not your work metric. What's your cost of entry? What’s your minimum equity? What's your cost of ownership?”

She notes the costs of maintenance and repairs for a large detached house are often glossed over, and says owners can find substantial savings with homes on this scale. Smaller lot sizes mean fewer landscaping costs. Smaller dwellings have lower utility costs, and ones that share walls have added energy efficiency.

While Quinlan has championed smaller builds, she has noticed in her practice an interesting dead zone. From between 650 and 1,000 square feet, it’s harder to get houses to pencil. She attributes this to the fact that a 550-square-foot one-bedroom house can have nice dimensions with premium kitchens and bathrooms, but adding extra rooms with limited overall space may compromise the rest of the design.

Like many developers working on infill and smaller projects, Quinlan grapples with the broader problems around how housing is constructed and funded in North America. “We have a very constrained set of building codes and financial rules of what can be built.” The result of those structures is “not a flaw in the system. It’s a feature. It's the way that our housing system is designed to operate, (with) zoning that intentionally makes housing expensive.” Hence the detached single-family home becoming the default option, or the “minimum viable product.”

In her work with the Incremental Development Alliance, Quinlan and her fellow board members advocate for the needs of smaller developers and help them navigate challenges to execute projects in their communities. In this work, she’s found that zoning is an impediment in at least half the projects she’s consulted on, and warns developers to be wary of any project that is “completely reliant on discretionary approvals.”

But she remains hopeful that “every city council in America could pass new zoning code tomorrow if they decided to,” and is pursuing that goal in her practice and through the Incremental Development Alliance.

As for her small homes, she’s already enjoying a nice feedback loop: “One thing that's been fun about this work in a small town is I know who lives in these houses that I've designed, and I see them at the grocery store, and a lot of them are still in those houses … And I have a couple of cases where somebody is selling one off-market to a friend because they're friends who've been coming over to dinner and love the house, too.”

Cities need more entry-level homes, but efforts to increase supply are often met with resistance. Iowa is considering a way around that issue: legalizing backyard cottages to increase housing supply without radically changing neighborhoods.